Bongga! What having Philippine English words in the Oxford English Dictionary means

MANILA, Philippines — Only in the Philippines do we eat dirty ice cream, cook in dirty kitchens, get kilig over romantic movies we watch with our barkada and pay KKB when we dine-in the carinderia where we are a suki.

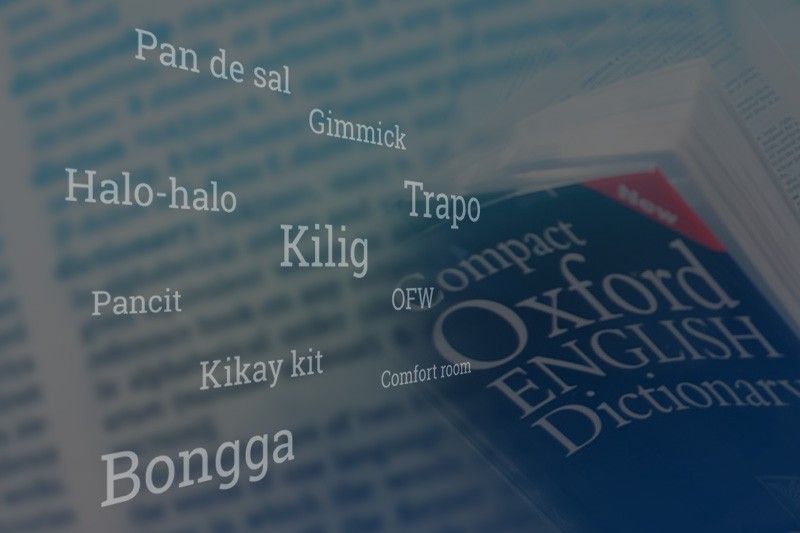

The rest of the English speaking world, however, may now use these Philippine English terms which are among the latest additions in the Oxford English Dictionary that will be published in its upcoming third edition. The dictionary’s last print edition, the 2nd, was published in 1989.

Filipinos may get kilig over the inclusion of our colloquial words in the 135-year-old English dictionary. But there is a more bongga reason why this is something to rejoice about.

“The reason is simple,” OED editor Danica Salazar said at a forum on celebrating Philippine contributions to the English language last June 14 at the Philippine Embassy in the United Kingdom.

“The OED is a historical dictionary and its very reason for being is not just to tell you what words mean. You can consult any old dictionary for that. Its purpose is to tell the history of the English language through the history of its words,” Salazar explained.

The OED editor said the dictionary is currently undergoing its first thorough revision and update since it was first published in 1928.

“English may have been a foreign language imposed on us by a colonial power but for good or for ill, it is now ours. As renowned Filipino writer Gemino Abad once said, ‘We have colonized it, too,’” Salazar said.

“Adding Philippine English words to the OED is about something we hear a lot these days — representation. We, in the OED, believe that the Philippines, just like this country, is part of the English speaking world. And as such, Philippine culture, Philippine history, the Philippine experience must be represented in this great work of scholarship on the English language.”

In October last year, the OED published 20 new Philippine English words that show interesting aspects of the country’s culture. The words were brought to the dictionary’s attention by Filipino speakers of English who answered its crowdsourcing appeal.

“By including coinages that were formally considered hideous aberrations, and adding audio pronunciations that put Philippine pronunciation alongside British and American pronunciations, we hope to do away with the deficit mentality that makes Filipino feel insecure of their English just because they use different words and do not have an American twang,” Salazar said.

“We think it is important for the Filipino words in the dictionary to be illustrated by quotations from works written by Filipino authors in Filipino publications.”

Here are some of the Filipino words in the OED — a historical dictionary that tells not just what words mean but also the history of the English language.

Pan de sal (noun)

The Filipino household bread, or “bread of salt” in Spanish, made its way to the current version of the OED. It is a bread made of flour, eggs, sugar, yeast and salt, more commonly dipped in a hot cup of coffee or hot chocolate in the morning.

Gimmick (noun)

Gimmick, in Philippine English, means “a night out with friends.” In other senses, OED defines gimmick as “a trick or device intended to attract attention, publicity, or trade.”

Viand (noun)

Viand is a meat, seafood or vegetable dish that goes with rice in a typical Filipino meal. An example of a viand is adobo, menudo, sinigang and the likes.

Bongga (adjective)

OED defines bongga as a word pertaining to “extravagant, flamboyant” and “impressive, stylish.”

Halo-halo (noun)

A popular Filipino cold dessert defined by Oxford as “a dessert made of mixed fruits, sweet beans, milk, and shaved ice.” It is believed to have been introduced during by pre-war Japanese migrants as “mongo-ya.”

According to historian Ambeth Ocampo, mongo-ya was a more basic version of halo-halo sold in the Philippines decades ago, with cooked red beans and shaved ice topped off with milk and sugar.

The Japanese were said to have monopolized the mongo-ya business, according to an autobiographical account of Kiyoshi Osawa entitled “A Japanese in the Philippines” published in 1981.

Kilig (verb)

Defined by the OED as the exhilaration or elation caused by an exciting or romantic experience. It was officially added to the dictionary in April 2016.

Despedida (noun)

True to its Spanish translation, OED defines despedida as “a going away party.”

Pancit (noun)

Simply meaning “noodles,” pancit is traced back to its Chinese origins “pian i sit” (convenient food) introduced by Chinese Filipino settlers from Southeast China.

Food journalist Nancy Reyes Lumen wrote in her book “Republic of Pancit,” Chinese suggests that pancit is eaten only on birthdays, and shouldn’t be cut down, as noodles symbolize long life and good health.

Kikay kit (noun)

Meaning “cosmetics case,” kikay kit was added to the OED in 2015.

Comfort room (noun)

More commonly called “CR” in the Philippines, comfort room is simply “toilet” as defined by OED.

OFW (noun)

Meaning Overseas Filipino Workers, the term’s popularization can be traced to the 1974 Labor Code enacted by the late President Ferdinand Marcos, barely 18 months after his declaration of martial law. Economic experts say this was in reaction to worsening dollar shortfall and unemployment.

Later, the Philippines saw a 949 percent increase in overseas workers from 36, 035 in 1975 to 266, 243 in 1986.

Trapo (noun, adjective)

Defined by the OED as “a politician perceived as belonging to a conventional and corrupt ruling class.” Its longhand version mean “traditional politician.”

— with Philstar.com intern Blanch Marie Ancla