The curator is present

Nilo Ilarde was hanging “Shark,” a work composed of a Cadillac rear, against a corner when I chanced upon him at Finale Art File (finaleartfile.com). Putting the last touches on “Sit Up Don’t Move Smile (reinventing black, 1957 to today),” on view until Oct. 31, he was deliberating on the work’s position, asking the gallery assistants to lower it for a couple of inches. For the untrained eye, it would not make a difference (the work would still require you to crane your neck), but for Nilo, the show’s curator, rightness is everything.

For the past 20 years, Nilo has been “hanging shows,” from one-man displays of emerging artists to mammoth exhibitions in public institutions. He is arguably the most in-demand and most respected curator working today. Yet Nilo, who is unmistakable with his lanky, towering presence, is not fully resigned to the term “curator,” preferring to be identified instead as an “exhibition maker.”

And how prolific an exhibition maker he is. Concluding yesterday at the Cultural Center of the Philippines was “What Does it All Matter, as Long as the Wounds Fit the Arrows?,” a tour de force of an exhibition presenting the works of 75 artists who are former students of the experimental stalwart and the acknowledged Father of Philippine Conceptual Art, Roberto Chabet. With co-curator Ringo Bunoan, Nilo exhausted the possibilities of multiple halls on two floors. From mostly representational paintings in the main hall, you were led to more conceptual works upstairs, most of which relied on chance, repetition, erasure. (Certainly, the exhibit was also a quiet assertion of Chabet’s continuing power in contemporary art practice.)

While “What Does it Matter” seems to generate its energy from a sprawl of unavoidably disconnected narratives, “Sit Up Don’t Move Smile” is more conceptually tighter in that it is driven by black, which Nilo calls “the color of abstraction.” As a predominant theme in an artwork, black commands and thwarts the viewer’s attention, allowing the work in question to be considered in its own terms as a unique object in the world. Whatever it may reference outside its sphere is purely accidental. It dissolves, like industrial acid, the imagination’s attempt to narrativize it. What you are looking at is a void — pure and simple.

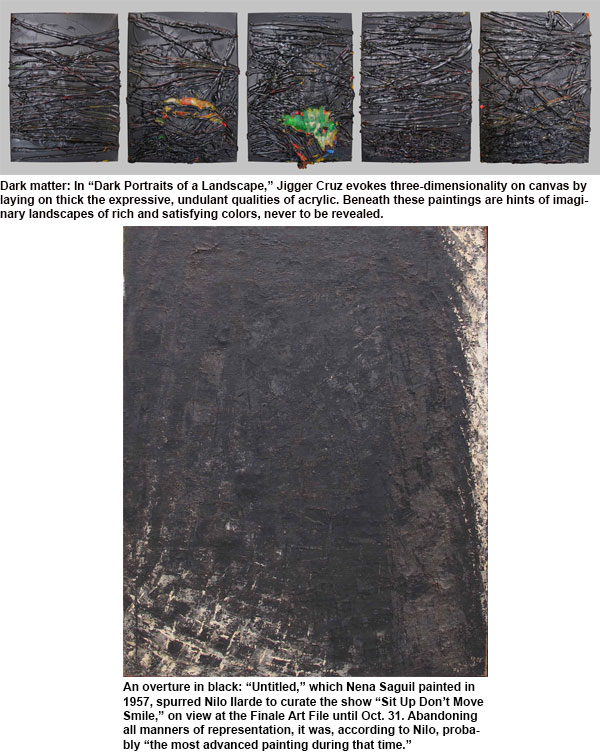

“Sit Up Don’t Move Smile” traces its origin to a 1957 painting, “Untitled” by Nena Saguil, which Nilo considers as probably “the most advanced painting during that time.” While Modernism was already in full swing during this period, with various artists already dabbling in abstraction and interrogating the representational mode, “Untitled” was something else for being meaningfully opaque, concealing signs of life, resisting thoughtfulness and interpretation. It dared all notions of conventional style. After all, who would hang a black painting in a Filipino house in the ‘50s? Upon seeing it 15 years ago in the residence of the artist, Nilo told himself: “It would be nice to curate a black exhibition around this work.”

Through various times and climes, the work had sat in Nilo’s mind like a dark, rectangular portal, waiting for other works to be let in. Nilo was quite aware of other artists who have pledged allegiance to this monochrome hue, but what interested him were works that were conceptually bent, indicative of an artist’s stylistic turn, or simply packed a punch. Nilo, in the course of those years, found affinities in the works of a diverse number of artists such as Johnny Alcazaren, Felix Bacolor, Vic Balanon, Ringo Bunoan, Annie Cabigting, Chabet, Jigger Cruz, Pete Jimenez, Elaine Navas, Mawen Ong, Bernie Pacquing, Gary-Ross Pastrana, Hubert San Juan, Gerry Tan, Maria Taniguchi, Tanya Villanueva, MM Yu, Reg Yuson, and Cos Zicarelli.

What frames the “Sit Up Don’t Move Smile” exhibition is “Sky Horizon” by Chabet, a series of empty rectangles attached with black cloth haphazardly rolled as though the work, hanging in mid-air, were simply abandoned. At once a conceptual and optical feat as it tunnel-draws the viewer’s gaze towards “O” by Taniguchi, it is defiant against endings; the fact that it was a work in progress for 40 years underscores this.

Seeming to provide a caption to the exhibit is Cabigting’s “My Black Square” in which she quotes, in her signature mark of reflecting, referencing and recalibrating the art of others, the art historian and the first director of Museum of Modern Art Alfred H. Barr, Jr.: “Sometimes it is said that art travels in a circle, but every generation must paint its own way. It is not satisfied with the black square which Malevich did. Each generation must paint its own black square.”

An artist of both gesture and effacement, Cruz contributes his own black square — five in fact — called “Dark Portraits of a Landscape.” Demonstrating the expressive qualities of acrylic to become three-dimensional, they also obscure, and inevitably smother, the hinted-at colors and richness of the suggested landscape. Beside Cruz’s suite of works is “Trangka,” a diptych by Elaine Navas which evokes a gate blackened by the elements and time. The visible drop bolt positions the viewer in relative safety to the onerous mystery that lies beyond the gate.

In curating a show like “Sit Up Don’t Move Smile,” Nilo rejects the temptation of using a scale model or applying a template. He looks at it as a collage (a genre in which he is considered a foremost practitioner), where “the wall is your picture plane; the paintings are the elements.” Working in situ, Nilo employs both artistic intention and intuition in arranging, placing and juxtaposing the works, with an eye toward engaging the viewer. Aside from that of individual artworks — and the tensions and resonances they spark when set against each other — the viewer will walk away with an appreciation of a singular, subliminal, but no less powerful work: the curated show itself.