‘West Side Story’is here to stay

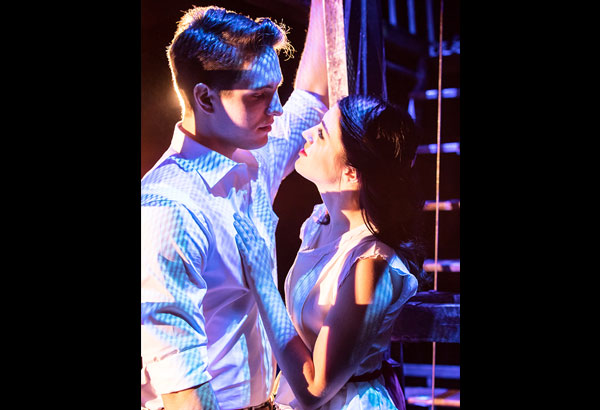

Caught in a bad romance: Kevin Hack and Jenna Burns play star-crossed lovers Tony and Maria in West Side Story.

To begin an appreciation of West Side Story is to know how it ends. Not happily. Forget any preconceived notion of musical theater — no elaborate costumes or sensational villainy here — and imagine a story so close to the truth that it could happen to any of us, today, in this very moment.

And to think that West Side Story first came to the stage in 1957.

We have unheralded, barely beloved playwright William Shakespeare to thank for this. Shakespeare’s stories have consistently been reinvented to suit more contemporary times (Amanda Bynes’ seminal classic She’s the Man was actually inspired by Twelfth Night), and West Side Story is one of the 20th century’s most well-known tributes to the Bard. West Side Story is a modern (well, relatively) retelling of Romeo and Juliet, set in the Upper West Side in New York City, at the tail end of summer. Two rival gangs — the Jets and the Sharks — are fighting for power in their corner of town, coupled with angry dance moves that prove just how serious they are. (In true teenage fashion, these 18-year-olds act like being the superior gang is the most important! thing! in the world! Which is exactly how a proper 18-year-old would think.)

Amid the beautifully choreographed gang wars are Tony — of the Caucasian Jets — and Maria — of the Puerto Rican Sharks — who fall in love at a dance and decide that, nope, we don’t care about these gang fights. We’re shackin’ up and beautifying the world with biracial babies, guys. This is it. (Again, very typical 18-year-old behavior.)

Like I said, the story isn’t destined to be kind to our fair lovers, but this isn’t why West Side Story has continued to resonate with audiences all over the world. More than being about star-crossed love, West Side Story is a cautionary tale of how far our dreams and ambitions can take us — and sometimes fall short. You see that in the way the Puerto Rican transplants (led by Keely Beirne’s show-stealing Anita) moan about life in America or the way the Jets try to keep their tempers in check with the trippy jazzy number Cool. The colors of West Side are deeply saturated, too: the stage is either set in fiery reds and oranges or deep, shadowy blues, depending on the mood of the scene. There is no in-between, as though to highlight a stark dichotomy between the two warring gangs. The Leonard Bernstein score and flashy choreography easily switch between classical, ballet, jazz and Latino styles. According to the show’s musical supervisor and principal conductor Donald Chan, this is what makes West Side Story stand out as a musical: the range of genres it allows in two tight acts.

This may be the enduring power of such a genre-bending show: it imitates life so convincingly. Life, like West Side, is a mishmash of contradicting things that somehow manage to work. It also tells a story that sadly reflects our current times. The fear, suspicion and anger towards immigrants in contemporary America; the distrust in state institutions like the police; and the disillusion of young people about the life they’d like to live. West Side has no specific protagonist to fight, because each character battles their own demons and somehow acts as another person’s antagonist in the story. Tony loves Maria but hurts her in the end; Maria’s naivety ultimately ends in violence; and Riff’s misplaced dedication to his gang ends up being his demise.

The cast all agree that these are troubled times, and touring a 60-year-old story that is just as provocative today as it was back then is not only a sign of its freshness, but a call to arms about all the work we’ve yet to do. “It’s an all-American musical,” says Lance Hayes, playing Riff, the leader of the Jets. Hayes is right, in so many ways: West Side Story is a musical deconstruction of the American Dream, one that rolls out beautifully thanks to the amazing cast and crew.

After the show’s gala night at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, I was able to speak to the some of the cast members and learn about their lives beyond their brief bios in the show program. To tour the world with people you’re only beginning to know, to battle a new version of jet lag in every city, and to deliver a stellar performance eight nights a week — that is no easy thing. Even snagging a role in West Side was its own challenge. Theater is a fickle and picky industry with a very short memory, and every cast member has had to jump through hoops to get where they are. You can’t just act, sing and dance; you have to be damn good at them all, and then, as they say, you have to be lucky, too.

“It’s especially harder for girls,” one male cast member tells me. “There are so many talented girls who can sing, act and dance — how do you stand out? Many of them go to casting calls as early as 6 a.m. They practically sleep there just to make it to the audition. And sometimes, they’ll think you’re not perfect for the role because you look a certain way. You really have to stand out, and a lot of luck comes with that.”

And then there’s the matter of actually touring. To be part of this cast and crew means packing up your life for months. Some of them have had to quit jobs, pause school, and leave their pets with loved ones, all for the chance to pursue their dream. In a case of art imitating life, the cast and crew of West Side Story are all on the way to building lives for themselves, and you can’t help but feel optimistic about what’s to come. It’s not because they’re good at what they do, but because you can just see how much they want it, and how much they’re willing to give to their audience just to bring a story like this to life.

West Side Story doesn’t end on a happy note. In fact, I would say that this note is a pretty miserable one at best. But to deny yourself a chance to watch this show in these trying times is to distance yourself from a truth many of us have begun to forget: that life, despite its darkness, still has some hope left in it.

* * *

West Side Story comes to Manila this August. For tickets and inquiries, visit facebook.com/ConcertusManila and www.ticketworld.com.ph.