Three women and a colony

Many of us, who’ve had the privilege and/or burden of a Catholic upbringing, grew up familiar with the concept of leprosy. The Bible was full of mentions of leprosy and lepers — 68 times in total. In the Gospel of Mark, a man with leprosy kneels before Jesus after the Sermon on the Mount, and says, “Lord if you are willing, you can make me clean?” Even in the Old Testament, leprosy was featured several times. In Leviticus, it is said that a person with leprosy is considered ritually unclean.

This is how many of us came to understand leprosy as children; not from the pages of a science book, but from the mythical explanation that to be a leper is to be unclean. It was an undesirable state of being, because it meant that you could not be touched or approached by society at large; even biblical figures in the Bible would often be portrayed as shrouded and separated from the crowd — a belief that sinfulness (the opposite of being godly and “clean”) would isolate you from the rest of society.

* * *

There has always been little sympathy for those living with leprosy. Although multi-drug therapy now exists, making the disease totally curable, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that in 2018, over 200,000 new leprosy cases were registered globally (mostly in developing regions where access to medicines are more difficult.) Leprosy still exists, and even the WHO recognizes that there is still stigma against those living with this disease.

The Philippines, for example, had a significant role in the history of leprosy. Culion island, on the northernmost part of Palawan was, for a time, the “largest and best known” leprosarium in the world, created during the American occupation. Culion was part of the American government’s plan in providing the country with some sort of public health policy, and the Americans believed that leprosy was a growing problem in the country.

Culion may be a beautiful place, touched by water on every side, but it holds a dark history that is rarely discussed. There was a public panic over the possibility of leprosy being spread, and Filipinos suspected of having leprosy were being captured all over the country. The first group of people with leprosy, around 370, were moved from a camp in Cebu to Culion in 1906.

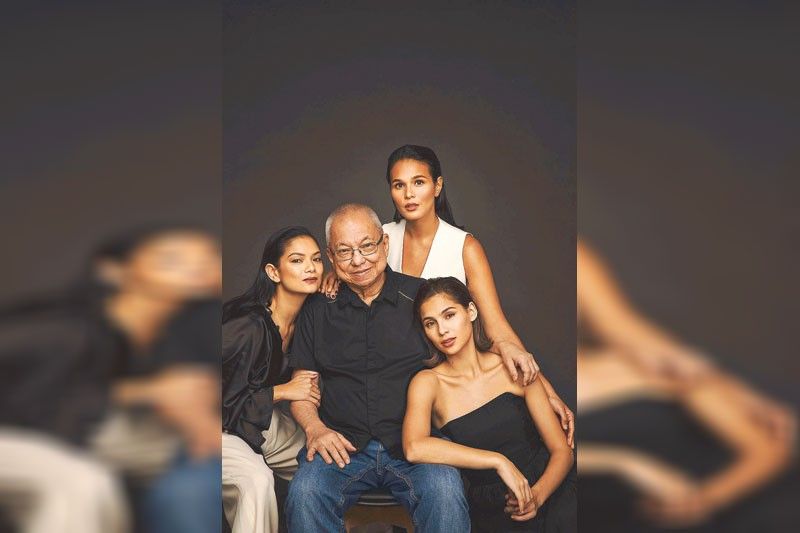

This is where the story of Culion begins. Directed by Alvin Yapan and written by Ricky Lee (of Himala, among many, many others), the story follows three women living in Culion in the 1930s — Anna, Ditas, and Doris. Each one of them have their own personal struggles: Anna (Iza Calzado) deeply longs for a child; Ditas (Meryll Soriano) is angered by how the disease has separated her from the love of her life; and Doris (Jasmine Curtis-Smith), whose innocence is shattered by an act of violence.

Since it came out on Dec. 25, Culion has been gaining attention for the powerhouse performances of all three actresses, as each one brings a different level of anguish to their personal tales.

In fact, the actresses themselves have found their own reasons to admire the characters they play. In a mild spoiler, Soriano’s character Ditas decides to run away on her wedding day because of her affliction. She gets a brief moment of repose when her fiancé Greg (in a much-lauded cameo by John Lloyd Cruz) visits her in Culion but is forced to stand away from her.

“Ditas is a great symbol of sacrifice, acceptance and love. Her journey inside the leprosarium and the reason why she went in say so much about her love for a person from the outside world,” Soriano says of her role. “At first, she thought leaving her life behind will bring her and her loved ones peace, only to find out that she had to face both her sacrifice and love in the eye and accept herself and her disease in order to make peace and move forward.”

“Memory plays a big part in her character. It crippled her in the beginning but was able to make it as a strength in the end, it made her stronger in her beliefs in the system,” she continues. “She never forgets about the past. She finds value in that. And it makes her a great teacher and leader in her own ways. “

For Calzado, she found an unlikely heroine in her character Anna’s stubbornness: “In some messed up way, I did admire that she was quite picky about who she let into her life. I’m a people pleaser, and I let so many people into my life, which I’ve always considered a strength. But I think there is a lot to be said about people who are emotionally unavailable. Cause then you have more time for people who truly matter in your life.”

“I’m fascinated that somebody can be like that,” Calzado continues. “She had her own progressive way of thinking, especially during their time. Like ‘wow, did a woman like this really exist during that time?’ To not be emotionally attached with a man you’re intimately involved with — not that I put that on a pedestal, but it’s quite admirable, because I can’t say the same for myself.”

Curtis-Smith says that Doris’ naiveté and hope make her someone to look up to. “Doris wanted to instill that hope in the students she taught and with that also came her naiveté, which is very evident whenever she shares a conversation with Anna and Ditas, her semi-tactless but innocent phrases often get the best of her and her intentions.”

The beauty of the film lies in more ways than one — highlighting the beauty of Culion, and the stories of the people in one of most well-known leper colonies in the world. But in the same vein of scriptwriter Ricky Lee’s renowned stories, Culion speaks volumes about Philippine society itself: the colony as a product of colonization, the enduring stigma of a curable disease, and the forced isolation of those whom we deem as undesirable.

In the film, Ditas says of Culion, they are living in a colony within a colony. And it’s a sentiment that remains true until today. “Politics aside, I firmly believe that we are still going through the same sentiment because of our mentality,” says Soriano. “We are very much a colony inside a colony. We still celebrate Western ideas more than really finding our roots and see what it can bring us and where it can get us.”

Calzado agrees that the line has a lot to say about contemporary society. “Meryll’s character delivered most of the social commentary that Sir Ricky wanted to convey. As a nation, we keep hoping for someone, another race, to save us. Or a leader that would save us. We let people into our country in the guise of helping us or saving us.” Calzado says. “But I think we have to be careful that we don’t end up getting raped as a culture, and be stripped off of our rights and everything we have. It’s a bit depressing, but it still rings true to this day. Sad, no? I feel like sometimes that I don’t know if our sense of freedom is really real.”

Curtis-Smith says that the line symbolizes our struggle to remain hopeful. “We struggle with holding onto hope,” she says, “but more importantly, that we do still hold onto it.”

Despite Culion’s dark past and the stigma still surrounding leprosy, the actresses all agree that audiences will still walk away feeling hopeful about the film — about how a band of outsiders became united by a common problem, who found connections with each other beyond a shared disease.

Leprosy has always been portrayed as a burden: for society, for those living with it, and for those who have been left behind. But Culion the film makes a very definitive answer to what the famed leprosarium really is: a failed experiment. Dr. Casimiro Lara, who was chief of the leper colony in 1942, had this to say after years in Culion: the colony failed to generate significant research in combating the disease and most importantly — that it failed to prove segregation as an effective means to curb leprosy.

The myths were wrong. Dividing people has never been the answer. And if you divide, and divide, and divide — those who remain hopeful will always find a way to come together. People, with their hopes and dreams and fears, will always unite.