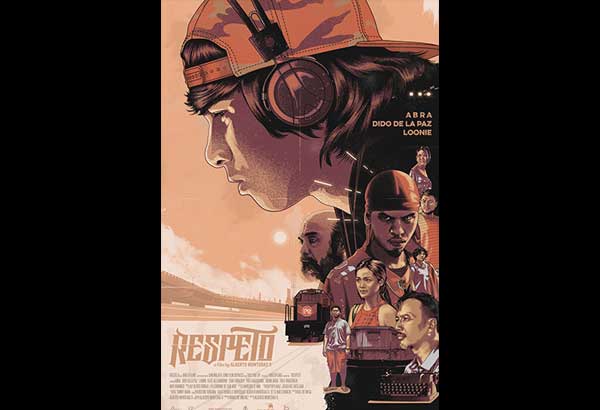

‘Respeto’ — in this age where there isn’t any

The Cinemalaya header is expected to be screened in cinemas nationwide.

MANILA, Philippines - Hendrix (Abra), the aspiring urban poet who peddles shabu on the side, has finally grabbed a chance to show off his rhymes at the neighborhood rap battlegrounds.

Accompanied by his crew composed of a scrawny but spirited lass and his burly best bud, he slips the bouncer a few grams of the illicit wares his older sister’s drug-dealing boyfriend ordered him to deliver and gets into the club brimming with patrons hungry for fighting words. He sees a girl he fancies waiting on the side. He’s ready for that moment of respect. He is however matched with a girl — tough-looking with the stereotypical hoodie to make her look that she belongs in a crowd of men who are all too ready to pounce at her if and when she shows signs of weakness. Hendrix starts to throw rhymes at her, mostly creatively-spun insults on her look, heft and gender. His opponent takes it all in and when she rebuts, she does it so without a sliver of being intimidated, sliding verse after verse about Hendrix’s incapacities and insecurities, eventually forcing poor Hendrix to pee right there on the spot, losing all the respect he risked the ire of his sister’s boyfriend for.

Treb Monteras II’s Respeto could have simply followed Hendrix’s evolution from a fledgling wordsmith who urinates when intimidated to the king of his hood like Curtis Hanson’s 8 Mile (2002), the Eminem-starrer that the film would draw the most comparisons with. Thankfully, Monteras’ endeavors are deeper than to map out Hendrix’s personal triumph. The film rap battles that the film thrives on are but windows to a sub-culture that has come to represent the potential power of words that this generation has allowed to surrender to shallow shame-hurling. What Monteras does is to connect the dots, to allow the sub-culture to bask in the glory of its more elegant and relevant predecessors. By having Hendrix become a student-of-sorts of Doc, a lonely old man (Dido dela Paz) who turns out to be a poet-activist during the Marcos era, Monteras gives what could have been just a film that aspires to be a window to contemporary hip-hop culture a semblance of heritage and a foothold in these most troubling times.

Respeto is an ode to the power of words.

It explores fully how rap has become an outlet for frustration, how it has evolved from a repository of escapist ideals such as romance and crass comedy into an avenue to brandish discourse. By displaying the ordered chaos of mixing the pops and cracks of Tagalog words with modern beats, the film conveys with lyrical logic how a community that exists amidst threats of violent displacement and other brutalities can be a hotbed of pertinent culture. The film does not differentiate the polished verses of decades past to the rhythmic recitations of today’s rappers. It only defines the generations, specifying with apt dramatic flair the shared vices and virtues to arrive at a point that the gift of conjuring words as weapons, whether for personal outrages or something more, is something that should be carried with both dignity and caution.

Respeto, however, is also about how words aren’t always enough.

In one of the key scenes in the film, Doc comforts Hendrix, who just recounted to him how he felt powerless while witnessing the girl he adores get raped, by telling him of a similar experience where he saw his wife and son become the target of atrocities of Marcos’ thugs. He lamented how he decided to exact vengeance one day by committing an act of violence on one of the thugs and how, in the end, it felt empty. In a way, Doc’s admission that while he is a king at crafting poems to suit whatever purpose, he still has to resort to move and act to air the most extreme of emotions feels like an admission that when push comes to shove, words, no matter how strong, are inutile. That poignant scene between Doc and Hendrix finds closure in the film’s sublime ending where Hendrix, who all throughout the film struggles to perfect his craft, comes of age by realizing that the only way to be noticed in his world where he is always cornered, always oppressed, always the victim, is to literally beat the bully, not with rhymes, but with a rock.

Last Aug. 13, Respeto rightfully won Best Picture at the Cinemalaya for its brave and artful display of the cycles of abuse our society is going through. Not more than a week has passed, a 17-year-old boy, probably as hopeful as Hendrix, was gunned down by cops without a hint of respect for life, all in their faithful observance of the government’s drug war policy.

Words aren’t and shouldn’t be enough to express our rage.