A remembrance of things past: Chu-Chu and Alex on Chito Madrigal

Chito Madrigal’s legacy: ‘She knew how to live, knew how to love.’

Consuelo “Chito” Madrigal always lived a double life. In the ’30s, she was Manila’s original “It Girl” but was also a lawyer who received a cum laude and a license to practice in Washington, DC. She was a serious businesswoman, sitting on the board of various banks and industrial concerns, but she was also the cofounder of such cultural phenomena as the Hyatt’s lunchtime fashion shows and the legendary club “Coco Banana.” (She bankrolled both the choreographer Gary Flores and designer Ernest Santiago.)

She was a beloved client of Harry Winston and traveled in style (with an entourage that included a chauffeur and a dresser.) Her name always appeared in boldface in society columns and she was a familiar figure at several chic New York restaurants, including Le Cirque, where the movie star Al Pacino would come over and kiss her on the hand. “Tita Chito” was also Mrs. Manuel “Manoling” Collantes, whose husband was acting Minister of Foreign Affairs. She was also the venerable Dame Consuelo of the Order of Saint Sylvester because of her generous charitable contributions to the Catholic Church.

And yet, what springs first to Chu-Chu Madrigal’s mind about her is the expression, “’Wag kang batugan (Don’t be a lazy bones)!” Tita Chito, she says, “was terribly disciplined and she demanded the same from all of us. If I was not up by 7:30 a.m., she would ask if I was sick or, heaven forbid, just ‘making lakwatsa.’”

Alex in a black dress by Sofie B and Chu-Chu Madrigal in Carolina Herrera in their home’s sunlit lanai

Daughter Alexandra, who grew up with daily visits to Tita Chito almost from the day she was born in 1990, exclaimed, “She would give me a little leeway on weekends and not phone till 8 a.m.”

Thus, it’s with a sense of poignant déjà vu that mother and daughter reminisce beneath a family portrait by Romulo Galicano. In it, Tita Chito is uncharacteristically dressed in a rather plain white cotton shirt and blue jeans. It is perhaps a deliberate decision to match the youthful exuberance of the rest of the family. She is, however, unmistakably at the very center of the painting, perched elegantly on one of the delicate, tapestried French settees in the green silk-lined sitting room in her home in Cambridge Circle in Forbes Park. The outlines of her collection of old masters can be spied behind her.

“When Alex was just 16, she asked for a portrait with Tita Chito. And when you come to think of it, it’s a peculiar request from a teenager, but Alex has always been an old soul.”

The Madrigal-Eduque home is a high-ceilinged house, with sunlight pouring in from very tall windows and is surrounded by a vividly green tropical garden. And yet, there is a distinct air of another time and other lives, an almost Proustian “remembrance of things past.” One first treads down a wide covered walkway paved with piedra china (the granite that was the ballast for the Manila galleons) that flanks two ponds.

In one corner of the formal sitting room is a Fabian de la Rosa oil work of a country maiden. (Fabian de la Rosa was one of the Philippines’ most important artists after Juan Luna and Resurreccion Hidalgo. He was the uncle and mentor of Fernando Amorsolo — and taught many society women how to paint, too.)

Chu-Chu and Alexandra on an antique Mariposa sofa of Anglo-Indian

“One of his students was my grandmother and namesake, Susana Paterno Madrigal. That’s why I just had to have a Fabian!” says Chu-Chu. Indeed, found in the dining room is a view of San Sebastian painted by the dowager Susana Madrigal herself when she was a young pupil of Fabian de la Rosa and a resident of the ancient borough of Quiapo.

In a hallway leading to another sunlit space is an enchanting view of old Manila in an ornate frame that once belonged to Tita Chito. Beneath it is a butterfly sofa of Anglo-Indian heritage. There is a sunlit lanai with more informal sitting and dining areas that appear to have been inspired by Tita Chito’s own entertainment zones.

“Tita Chito,” says Alex, “was extremely forward-thinking. All the words that are in fashion in millennial-speak could easily describe her. She was authentic — almost brutally honest, in fact. She never minced her words and she always told me that it was all right to be outspoken as long as you were respectful. She believed in accountability. She believed in woman empowerment. She would say it was important to work and have your own money and to never be dependent on a man. But she was also a great romantic and said I should marry for love!”

“And, don’t forget, she was the original champion of LGBTQ rights,” adds Chu-Chu.

Alex continues, “It was the everyday habits, the banter that was the legacy she left behind. We are who we are today because of those everyday interactions, and essentially, because of her.”

“Tita Chito, for example, was punctual to a fault. If I was just one minute late, she’d leave me in the driveway!” exclaims Chu-Chu.

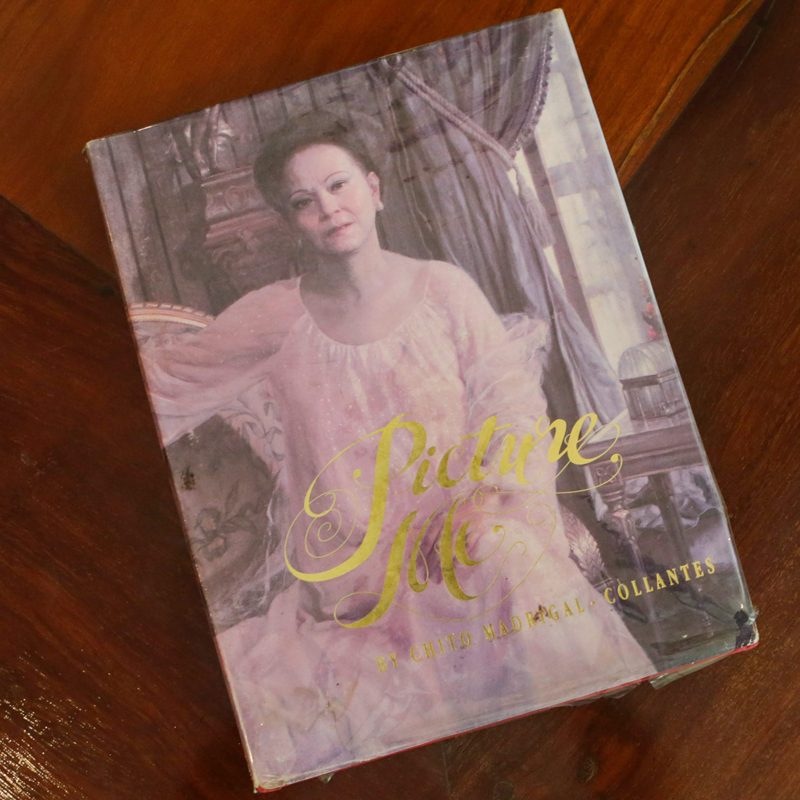

Chito Madrigal for Life magazine, circa 1949

“And even if it was a shopping date at Bloomingdale’s, she’d insist on arriving at 9:45 on the dot and you know that made a lot of sense, because you had the store all to yourself,” Alex says with a grin. “But make no mistake: she was not a snob. When people would label others as ‘social climbers,’ she would always retort, ‘We must all remember that at some point in our lives we were all social climbers — and there is nothing wrong with that as long as you don’t harm anyone.’”

The Madrigal matriarch began the tradition of systematic “paying forward.” “It all started in 1997, when Tita Chito began to help people in Bicol informally. Our grandfather, Vicente Madrigal, was from Albay and Tita “Chito” chose to honor him by beginning there. At the time, Bicol was the third poorest region in the Philippines. It started with scholarships for 50 students in the Ateneo de Naga. So far, more than 117 have graduated. Next, she started micro-financing that eventually served 12,000 members and soon covered four housing sites. The Consuelo ‘Chito’ Madrigal Foundation now supports best practices in agricultural technology in Bulacan and the Visayas. In Payatas, we have a training program to teach culinary and hospitality skills. It’s all about helping others but not through dole-outs. Tita Chito wanted people to have their dignity by making them partners in the enterprise, by doing their part by working. She would always tell us that helping others is a privilege.”

Not surprisingly, mother and daughter have begun their own foundations. Chu-Chu is active in “I Can Serve,” a non-profit run by Kara Alikpala that focuses on the early detection of breast cancer. She supports a few key patients a year, from the beginning to the end of their treatment.

“It’s incredibly difficult and the costs are prohibitive if you are on a small salary, or even if you have a large one!” she says. “I pick the patients who need the most help. I believe that if I can save just one life a year, I’ll be very happy. So far, I have taken three women through the entire course. I call them my ‘Cancer Samurais’ because you need to be fierce to survive.”

Alex, for her part, said that it all started when she had to write a thesis for her course at Barnard College, Columbia University. “I said to myself, if I am going to work 400 hours on this thesis, I’d like it to be on a global issue, something that was relevant and that was for the greater good.”

That led to the creation of the MoveEd Foundation, which provides “early education” to preschool children in underserved communities. It’s coupled with an in-class feeding program that also monitors the youngsters’ weight through this critical age. To date, in just six years, the foundation has reached 23 schools in Navotas, Pasig, Parañaque, and the third district of CamSur, benefiting almost 1,000 students. Currently she has a capsule collection in partnership with Marga Nograles of Kaayo to raise money for school kits for Marawi chidlren.

Is a career in politics on the horizon, one wonders? Alex says, matter-of-factly, “I have found that you don’t actually have to run for public office to help others.”

Chu-Chu adds, “Let’s just say that I also learned from Tita Chito to ‘never say never,’ and to welcome every opportunity.”

What do you think is Tita Chito’s most important life lesson — and legacy? I ask.

Alex says quickly, “She knew how to live, knew how to love, and most importantly, she knew how to give back.”