Did we really land on the moon?

It’s a telling sign of our times that you can sit with your laptop and bounce around between opposing documentaries on the same subject. Take the July 1969 US lunar landing mission known as Apollo 11. One visits Netflix, and the series Conspiracies flashes in your face. One episode features the click-bait tease, “Was the moon landing a fake?”

Of course, this has been a standard conspiracy theory trope since, well, men first landed on the moon, and the Conspiracies episode does its darnedest to sow confusion and doubt about the very elaborate, expensive and meticulously planned moon mission known as Apollo 11. We’ve already seen the documentary Room 237, which amassed fringe fan theories about Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, one of which is that the director was hired by NASA to fake the moon landing on a film set located in Area 51. The theory goes that Kubrick was later forced to keep his participation a secret, so he passively-aggressively dropped all kinds of clues in The Shining, such as Danny Torrance wearing a lumpy Apollo 11 sweater in one scene.

Nailed it!

For conspiracy theorists, all it takes is a set of adjacent facts for causality to exist. The sheer mass of evidence showing otherwise is no match for the paper-chain links that seem to suggest a government conspiracy lurks behind every shady door. The Conspiracies episode points out that astronaut Gus Grissom died in a fire inside a capsule during a NASA preflight testing, along with two other astronauts, and notes that he’d been “critical” of the moon mission just days before that.

Silenced!

Of course, more extensive research shows that the Apollo program was riddled with costly mistakes — test rockets blowing up on launch pads, jet test flights ending in disaster. Many astronauts died. Why NASA saw the need to kill off one mouthy astronaut, rather than simply cut him from the program, is something only conspiracy theorists can truly grasp.

Of course, we live in a world where truth is under fire every day. We have competing narratives huffing and puffing on our screens, attacking us with exclamation points and explosive comment threads. Navigating “the truth” is a head-spinning enterprise in the best of times, because “the truth” only exists in itself; our impression of every event passes through a subjective lens, and we are more than willing to seek assistance from outside sources when interpreting those events. Thus, we look for perspectives from shows like Conspiracies. (The uncanny is fertile ground for the conspiracy-minded. One episode looks at the “Black Dahlia” murder case, and wonders why an aspiring actress was left dead, surgically severed at the waist, in a Hollywood park in 1947. Uncanny! Creepy! Was it the work of police covering up for Hollywood moguls? Was it the mob? Was it an evil doctor afraid of blackmail? That’s the theory posited in Conspiracies, and — surprise! — there’s even a connection to the Philippines: Hollywood surgeon George Hodel, who was investigated for the murder, fled the US in 1950 to live in the Philippines until his death in 1990; his son still maintains his dad was the killer. The “Black Dahlia” remains a legitimate murder mystery, still unsolved after 70 years. Which makes it a wonderful vacuum for conspiracies.)

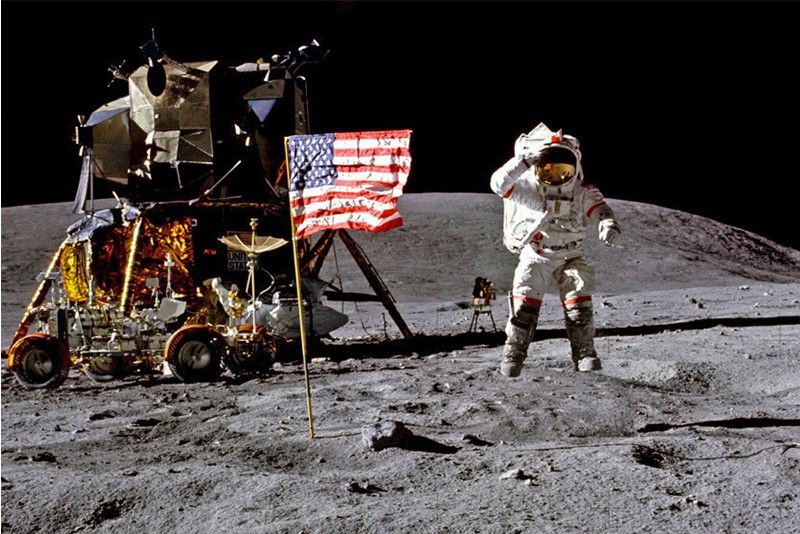

Most uncanny for moon landing doubters are those crisp images of astronauts, cavorting around on the lunar surface. They say it looks too real — “like a movie set.” Why is it so bright? (Sunlight hits and reflects off the moon’s surface, illuminating its every crater, as we can see very plainly every night when we gaze upward from earth.) And why didn’t the Russians ever make it to the moon? (They tried. They failed. They did send an unmanned probe that landed on the surface in 1959.)

One crystal-clear document of the moon mission comes in a new documentary released for the 50th anniversary. Apollo 11 gathers, with very little narration (save Walter Cronkite, NASA engineers and three space-bound astronauts), archival film and images from hundreds of hours of 70mm footage, some of it in hyper-real detail, gathered by NASA to record the historic launch. The film is moving, almost heart-pounding, even if you know the ending. The astronauts sit in a tiny capsule above a massive rocket, ascend into the skies as a million Floridians watch from the Cape Canaveral banks (and millions more live on television). Rooms full of engineers monitor the progress of the flight — eminently convincing, unless you believe they’re all actors or in on the conspiracy. We see the Apollo 11 capsule circle the moon and the lunar module descend on the Sea of Tranquility. We watch as Neil Armstrong steps down a ladder to touch the moon’s surface — this time in strikingly clear footage taken from inside the lunar module, not those fuzzy, high-contrast TV images sent across 186,000 miles of space through a Unified S-band and downloaded onto an FM subcarrier back on earth. The photos taken by “Buzz” Aldrin during the astronauts’ several hours of moonwalking are riveting, otherworldly — which they, indeed, spectacularly, are. (Uncanny!) They capture a location that no other human had ever managed to take a selfie on before July 20, 1969. (And only a handful since. Another conspiracy query goes: “Why didn’t the Americans go back to the moon?” They did, on five other missions during the 1970s. Remember those moon rovers, the ones designed by Pinoy mechanical engineer Eduardo San Juan? They’re still up there, as are five of the six planted US flags, according to high-resolution images taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2012.)

And finally, presented with the best available evidence — crystal-clear documentary footage — the conspiracy theorists will still shrug and say, “Well, sure, it’s easier now for NASA to fake even better footage to back up the 1969 hoax. Just look at CGI!” What can you do in the face of this kind of skepticism? Just hire a boat and live on an island somewhere, away from all the digital battles? Maybe.

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t dismiss all conspiracy theories. Governments lie, lie, lie. Political leaders lie, lie, lie. But I’m selective about my conspiracies: I cherry-pick them. I won’t take every crackpot theory as equal on its face.

The real danger of conspiracy theories is not just their seductiveness (everyone loves a mystery), but their corrosiveness. You have to ask yourself who benefits, say, when a US president contends — all available evidence to the contrary — that Russia never meddled in US elections in 2016 or that climate change isn’t happening or that the previous US president wasn’t born in America. Consider the provenance of the conspiracy peddler. Consider the motive.

But if you start from the notion that truth simply doesn’t exist — as a smug young lawyer, now working for the Duterte administration, tried to convince me during dinner one night — then all that is left is competing piles of facts. And even those facts are constantly under fire. We all become not just armchair pundits, but armchair Pontius Pilates, shrugging at every mystery: Quid est veritas? What is truth?

No wonder the truth is an endangered species.

* * *

Follow on Instagram @scottgarceau.