The last rock star; Carmen Guerrero Nakpil

Chitang was ‘the best National Artist for Literature the country never had,’ Deanna Ongpin-Recto says.

MANILA, Philippinjes — You can’t be a rock star without enraptured fans and a handful of stalkers — Mom had plenty of both. It’s funny to think about it in the age of Twitter, but when she would tap out her columns on an analog clunker called the “typewriter,” the Manila Times had a circulation of one million readers a day. (Think about it: this wasn’t views for free, but people plunking down real money to get the lowdown on the world.)

Hollywood’s biggest leading stars — Cary Grant and Clark Gable, Humphrey Bogart and even Lauren Bacall — played hard-boiled reporters. Newspapermen starred in their own comic books: Superman’s alter ego — and Spider-Man’s too — worked for the press. Op-ed columnists (like Mother) were, of course, newsroom royalty and were courted not only by the rich and powerful but also by competing papers that sniffed out the first hint of discontent, faster than you could say “LeBron James.” Mother, in fact, had a strict “no-edit” rule in her contracts, which meant that not one word — even if it had been misspelled inadvertently by her typist, little ol’ me — could be changed without a quick consult.

President Ferdinand Marcos and Carmen ‘‘Chitang’’ Guerrero Nakpil are flanked by newsmen Joe Guevara (Manila Times), Napoleon Rama (Free Press) and JV Cruz (Manila Times).

Of course, I didn’t know any of that when it was all happening — although I would occasionally be allowed to read the adoring letters from readers. As far as I could tell at the time, Mom 0seemed to have succeeded in spite of herself, certainly in spite of her famous last name and in the rambunctious world of the newspapers, in spite of her “Ermitense” manners. Ermita before the war was the closest thing Manila had to the Kardashian Kalabasas, a tightly-knit equivalent of a “gated community.” Older sections of the city, like Sta. Cruz or Binondo, were comprised of trading houses cheek by jowl with the ancient mansions of the rich. There also lived the artisanal craftsmen above their shops or restaurants. There was no such thing in Ermita by the sea. It was a French Riviera composed of the villas of the new American officialdom and Filipino landowners and professionals.

This was the world that went up in smoke in World War II, after which Mom was forced to reinvent herself as a newspaper contributor named “Josefina Cruz,” in order to prove a point that she could write as well as her then-already famous older brother Leon Ma. Guerrero. She then broke tradition one more time by adapting the self-made nickname “Chitang” to replace the feminine “Carmencita.” Mom soon became larger than life — at one point, becoming famous enough to be invited to star in her own movie to be titled appropriately, Amazona. (She turned that down. Lord knows what would have happened, if she hadn’t.)

Imelda Romualdez Marcos, Muammar Kadaffi and Carmen Guerrero Nakpil

She wrote landmark essays on Filipino women — and men— and the culture they lived in, the whole time presiding over a remarkably modern “blended” family — spanning three marriages (hers, his, and theirs) and seven children. (Two of her children remain the most famous: Gemma Cruz Araneta and Ismael “Toto” Cruz, named after her first husband; two others passed away before her, Ramon Guerrero Nakpil and Carmina Nakpil Dualan. Three more survived, myself and two more siblings, Luis Guerrero Nakpil and Nina Nakpil Campos.)

As a little child, I actually thought at one point that Mom was Lucille Ball in I Love Lucy, a dizzy housewife that specialized in burnt dinners and fun misadventures. The screwball aspects of her life almost certainly came from having to produce a daily column while running a very much expanded household — and refusing to fall into the expected, gender-specific stereotypes. (For good measure, Mom would make sure I went to driving school while the boys had cooking lessons.) She never approved of pets either, saying with such conviction that “animals should either be worshipped or eaten” that my French poodle (an ill-advised gift from my father) ran away from home.

Carmen Guerrero Nakpil with President Ramon Magsaysay, 1955, at the inauguration for the National Press Club, designed by her husband, architect Angel E. Nakpil

Mom would routinely begin the day on the telephone, with a barrage of calls from fellow newspapermen and various gossip-mongers, her editors (including one fellow called Rudy Tupas, then editor of the Sunday Times Magazine, who somehow persuaded her to write for the first time about the terrible war years. I always suspected that, in retaliation, Mommy paved the way to make him Ambassador to Libya.) She also had her own “brat pack” of feminine conspirators. These were equally broad-shouldered women, with big personalities, including Estrella Alfon (the famous short-story writer; Mom also tried her hand successfully at those); Mile Valencia (society page editor), the formidable Kerima Polotan, as well as writers Cita Trinidad and Mary Tagle. Lyd Arguilla of the Philippine Art Gallery was also her friend and one of its first incarnations as the country’s only purveyor of abstract art was in the Taft Avenue building that belonged to my father’s family. Her absolutely best friend (from that other Ermita life) was her cousin Leni Guerrero who started the bistro Costa Brava. It would be a role later taken up by the doyenne Consuelo “Chito” Madrigal. Fast friends through their twilight years, they would settle into a comfortable conventionality of cocktails and society suppers.

Chitang (right) with daughters, Lisa Guerrero Nakpil and Gemma Cruz Araneta, circa 1978

She adored poets. Jose Garcia Villa to Yevgeny Yevtushenko to Virgilio Almario all became her friends.

Mom was an ultra-nationalist, perhaps the most difficult aspect of her politics as a child growing up. I can still remember that Christmas day when she caught me red-handed with a spray can of artificial snow that I had bought with my own allowance. “There are no white Christmases in the Philippines,” she bellowed, explaining its real origins in a frigid Game of Thrones environment.

She was a throwback to the world of turn-of-the-century nationalism — that made it more important to speak and write eloquently in Spanish and, later, English, than in Filipino, simply because they were the languages of one’s colonial betters. (Mom was convinced that if we had stayed in loincloths instead of top hats and cutaways, we would have gone the way of extermination like the Sioux or Apache. Because of this, it was important to her not only to have exquisite manners and to dress with a certain panache as part of a political philosophy.) She was also driven to excel — not only in a field dominated by men, but also to become as “global” in as excellent a way as possible. Thus, she wrote for the SouthEast Asian Press and delivered lectures in various countries.

Lisa with older brother Ismael Guerrero Cruz, alongside the towering topiary from President Rodrigo Roa Duterte

Yet she was modern. Devouring newspapers and books from New York and London, she was always up to date. She loved technology, anything with moving parts or that hummed. (Admittedly, she threw an expensive computer I had bought her out the window when it failed to save a page of prose.)

The truth of the matter was that she had become patron saint of not just women journalists and writers of several generations but also all female achievers, in general, of every stripe and political persuasion — no matter where they excelled. She had become a role model for all modern women, full-time housewives or working women, single mothers or those married. Writer Zenaida Seva said, “I was in awe of CGN from the time I began reading her column, ‘Consensus of One,’ in the Sunday Times Magazine. The Philippines just lost an iconic essayist, journalist, historian and author. Her passing diminishes us all.”

Mother’s enormous gifts would cross gender lines. Leo Garcia, the first dean of the Ateneo Loyola School of Humanities, remarked that “Horacio V. de la Costa — one of the country’s most brilliant historians — thought of her as a foremost nationalist with a superb command of English, ‘that was obscenely the best’ in the country.”

Lisa Guerrero Nakpil with nephews Rep. Luis Nakpil Campos and Joey Nakpil

Despite these learned opinions, Deanna Ongpin-Recto, said, Chitang remained “the best National Artist for Literature the country never had.” Writer Rony V. Diaz added, “I am puzzled by the failure of the National Commission of Culture and the Arts (NCCA) to recognize the extraordinary talent of Carmen Guerrero Nakpil, one of the country’s most gifted writers. She died without that accolade. Was it because she was associated with Ferdinand Marcos and Imelda Marcos? If my guess is correct, then even our literature has been corrupted by politics.”

Mom was ultimately transcendent. She had the gift of distilling the difficult into the relevant (summing up, for instance, almost a half century of history into her now-famous quote — “300 years in a Spanish convent, 50 in America’s Hollywood.”). She made Philippine politics and our cruel history readily understandable (no mean feat in itself) and even the stuff of the Twitter-verse.

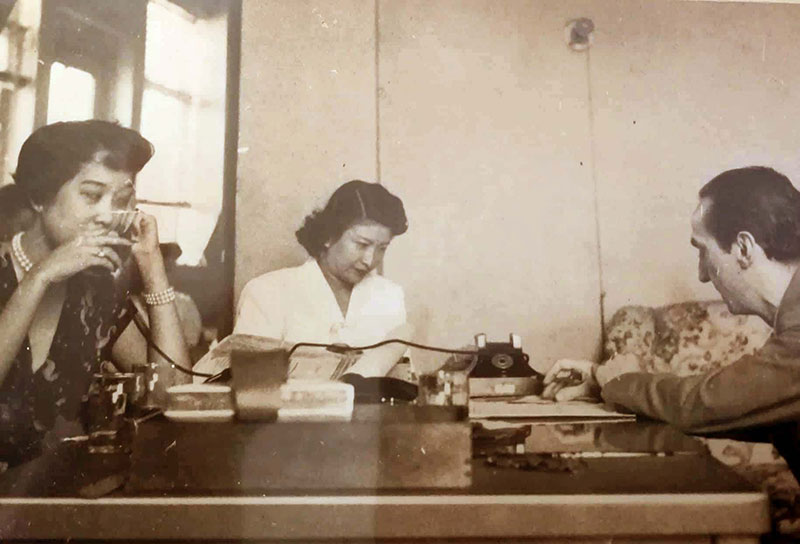

Chitang at work for the Evening News

And because, as I have always liked to think, one is judged by the quality of one’s enemies, at the height of the Cold War, Mom would receive letters tied with black ribbons and on one particular occasion, even a “tanim bala” in the mail. In fact, she would have heartily agreed with D30’s US-bashing and his strategic pivot to Russia and China. (She was, in fact, among the first group of Filipino journalists to travel to the PRC, a most dangerous enterprise since foreign relations with it had not been officially recognized.) Mom would have delighted in the current president’s brandishing photographs of the American carnage in Mindanao. She often wondered if Filipinos would ever be interested in their own history: here was her answer.

Into the wild blue yonder: Carmen Guerrero Nakpil in a plane in 1947

At her wake, lavishly decorated by an artistic sister-in-law, Morita Roces Guerrero, in the shades of Monet’s mornings at Giverny, there were accolades and presences from one former first lady, a hero of the EDSA Revolution, dozens of Rizalistas, and a cross-section of Filipino art, culture and business. Eight-one overwhelming wreathes from capital-market firms and heritage conservationists, rotary clubs, cabinet ministers, six senators and several ambassadors, three writers’ guilds, universities, high-rises and hotels, distinguished relatives and pals, art galleries and an auction house, media and newspaper companies. Close to midnight on the last day of her wake, a towering topiary from Philippine President Rodrigo Roa Duterte arrived, announced by the office of Mr. Bong Go. Like the portrait by Federico Aguilar Alcuaz that stood beside it, it was a fitting tribute to my mother’s enduring legacy.

Did I learn anything from her apart from that? Early on, I realized that Mom was sui generis, one of a kind. It would have been impossible to regard her life as some sort of template. I think I had the good sense to realize that there was only one way to deal with a natural phenomenon — that was simply to get out of the way.