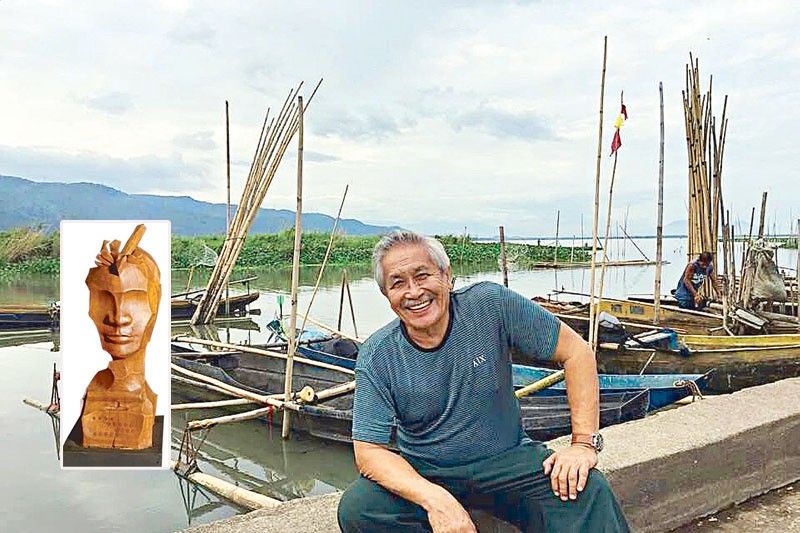

Manny Baldemor imagines verses from blocks of Molave

During these long spells of community quarantines and lockdowns, artist Manny Baldemor says his brushes and colors were able to “take a rest.” He sat down and began writing poems — about the origin of dance, the pledge of the sabungero, the shifting music of feasts and funerals, and how the new normal is nothing but the old norm in his quiet hometown of Paete, Laguna.

Baldemor admits to always wanting to be a writer. So, he crafted these mellifluous verses in Pilipino about the lives of common folks as well as the architecture of spectacularly simple living. Much like his own paintings that have graced the faraway walls in Madrid, Munich, Berlin, Dusseldorf, Prague, Paris, Vienna, Warsaw, Budapest, Moscow, Copenhagen, London, and New York; or have adorned those wonderful UNICEF greeting cards aimed at providing emergency relief for vulnerable children.

He has writing implements at his bedside, so that whenever he thinks of a line or a turn of phrase — even in an ungodly hour at night — he can easily jot it down. “Otherwise, kapag hindi mo isulat agad, parang nilista mo lang sa tubig (laughs).”

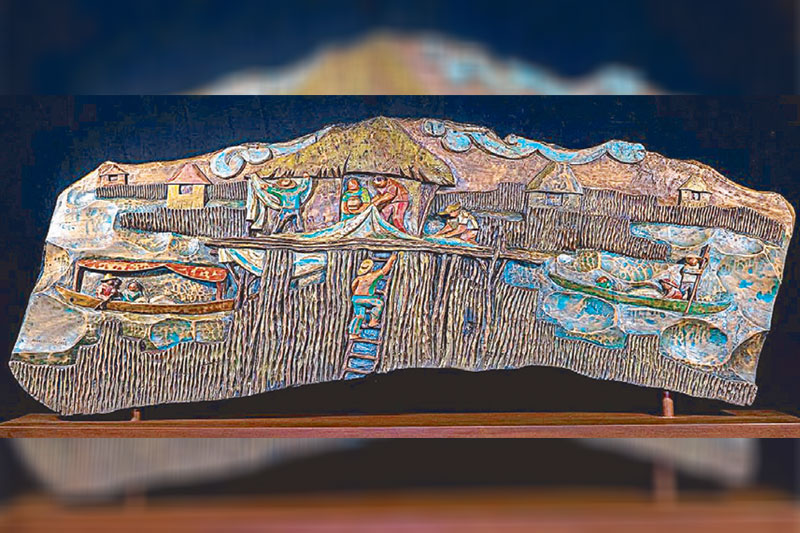

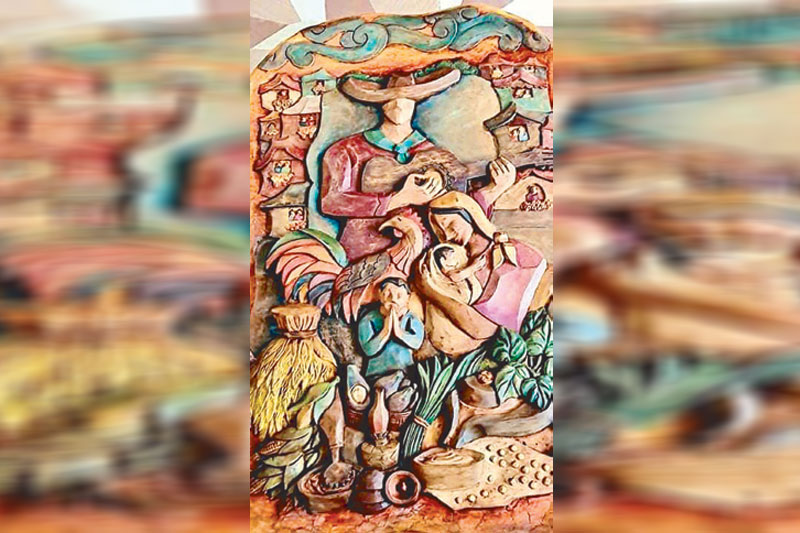

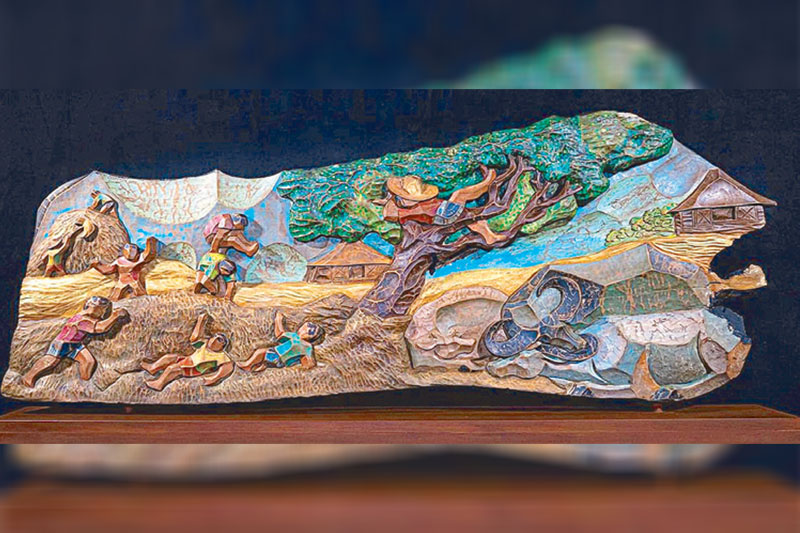

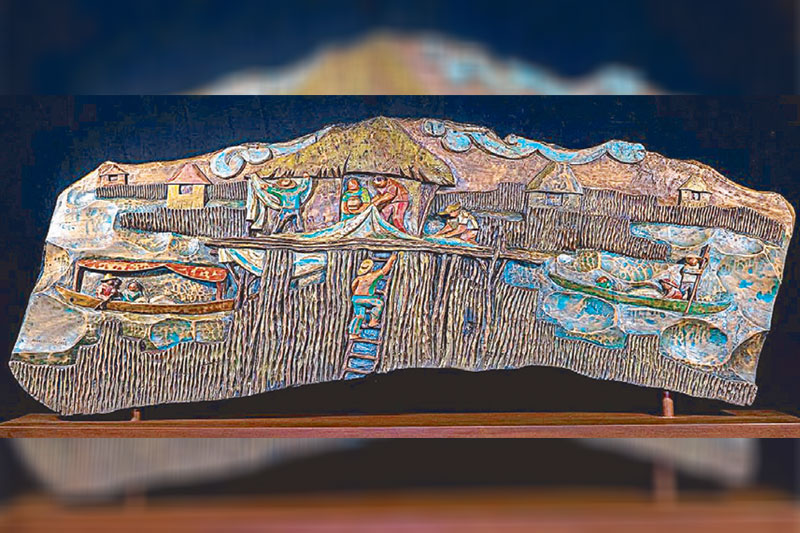

He posts the poems on Facebook, with titles such as “Kundiman ng Dyaguar,” “May ‘K’ din ang Kabayo” or “Tele-Larawang Normal.” They are accompanied by his own woodcarvings and bas reliefs — sculpture being another one of Baldemor’s passions.

It is a sort of back-to-the-roots trip for the artist. He was into woodcarving in his youth in Laguna. The town of Paete (its name derived from the Tagalog word “paet,” meaning “chisel”) is known for its woodcarvers and craftsmen and their intricately carved statues, santos, pulpits and church fixtures. Before getting into chisel-work, Manny painted papier-mâché figures or taka sold during fiestas. “That why my colors up to now are folksy,” he explains. “Festive. Mahilig kasi akong mamyesta eh. Kulay Pasko, kahit hindi Pasko (laughs). No angst. Wala kasing ‘masamang tinapay’ kapag probinsyano ka.”

For a time, the young Manny painted kartelon or show-bills or posters, which were changed every two weeks in cinema houses in Sta. Cruz, Laguna. “I was 14 years old at the time. So, my portraits, eh hindi pa masyadong kahawig sina Fernando Poe Jr., Zaldy Zschornack or si Jess Lapid, pero pag nilagyan mo ng napakalaking letra, nakaka-mukha na (laughs).” “FPJ” in bold, screaming fonts pasted on scenes of mayhem and melodrama.

If you are a woodcarver, says Baldemor, it is important to have “X-ray eyes.” He expounds: “Once you see a piece of wood, you should know right away what (the shape of the wood suggests), whether it is Kristo, a tree or a nude woman.”

B

aldemor as a teen was tasked with making the pardon, or pattern, for the other woodcarvers to copy. “’Yun ang nagpa-aral sa akin sa kolehiyo.” Manny, the son of a fisherman and the grandson of a director of zarzuela, says, “Sa Paete, ang panaginip ay nagsisimula sa silong ng bahay — kasi dun ka nagu-ukit or gumagawa ng taka.” And from that lowly basement, you shoot for the stars.

Thus, the young Manny, who put himself through college by working with his hands, has now become the well-travelled, multi-awarded, well-respected senior visual artist Manuel Baldemor, although holed up in his own locked-down corner just like the rest of us. The difference is, the man writes poems, takes these massive blocks of molave or mango, and illuminates what is dear to his heart: ang pagbabalik sa simpleng buhay sa probinsya.

“Bukid, magsasaka, mangingisda, pagpitas ng santol sa puno… tuluy-tuloy lang ako sa pag-ukit. I have around 500 pieces of sculptures in my studio in Paete. You know, painting is relaxing, but sculpture is hard work. Just sourcing the material is difficult. After a storm, you need to go with your friends and look around for felled trees. Mahirap mag-ukit, time-consuming, nakakapagod, nasusugatan ka pa. Pero imbes na ako mag-aerobics, eto exercise ko (laughs). Troso ‘yung hinahagupit mo eh.”

Baldemor knows the place of origin of a piece of timber, depending on its haspe or wood grains. “The haspe of wood is beautiful or dramatic if the tree comes from typhoon-battered areas, especially in the Visayas or Bicol. Kasi maliit pa lang ’yung puno, lumalaban na sa bagyo o sama ng panahon. I sometimes paint on sculpture if the wood grain is not so interesting.”

His favorite is the molave or mulawin. “Kasi ginagamit ito bilang haligi ng bahay or part ng riles ng tren — paghataw mo ng carving tools dapat malakas, kasi lumalaban.”

Manny jokes that he sometimes smells of carabaos, among other things, since whatever the scent of the sap is or the secret story of the wood itself stays on the skin of the sculptor, along with his sweat and sometimes blood. “So, paano mo ibebenta ’yung bagay na parang bahagi na ng katawan mo?”

Nowadays, the artist lives in Manila but maintains a house that stands in the center of Paete, looking out onto the town plaza and the church of Santiago Apostol. “Dinig ko every Sunday ang homily ng pari,” says Manny. “Dumungaw lang ako ng bintana, nakikita ko na subjects ng art ko. Ang pulso ng bayan ay nasa plaza.”

And that same pulse throbs in the works of one Manuel Baldemor — whether in his cityscapes painted in iridescent colors, his poems about finding paradise in the provincial, and the carved heart of wood depicting shapes and stories dreamt up only in basements.