If Filipiniana is a flower, then Jaime Laya is a gardener

For a second there I thought Cabesang Tales would show up, his salakot almost like an amulet against the long spell of rains. Or Amorsolo’s women bathers, their fingers wringing water from their tapis — brown against the blueness of the brook. Or a dude in sinamay straight from Damian Domingo’s watercolors, carrying a tapayan across the plaza. Or even brother Leon coming home, wife in tow.

In this enclosed garden of caimito, avocado, mango, duhat, atis, kalachuchi, and ylang-ylang trees (a nipa hut here, a phalanx of capiz windows there), you would think time stopped somewhere when it was still more idyllic, romantic — before things became globalized, mechanized and terribly more confused. Well, the sight of the McDonald’s golden arches jutting out from the stonewalls brings you back to the Here and Now of crime, grime and two hours of Grab time to get from Katipunan Ave. to Port Area.

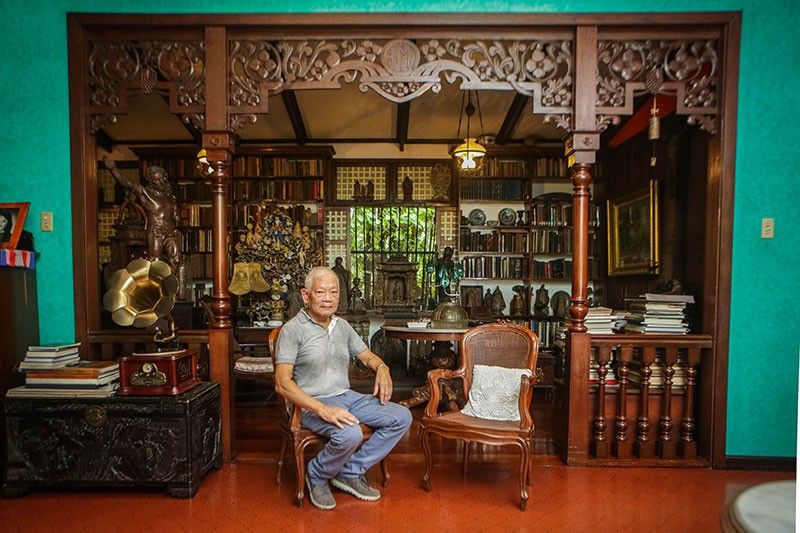

But, inside Jaime “Jimmy” Laya’s house filled with books, art, maps, stamps and santos, you could still spot bato-bato, maya and Maria Capra birds waiting in the garden for the homeowner to throw birdseeds their way.

“Except when a cat or two lie in wait,” says Dr. Laya.

The man is an aficionado of all things Filipiniana. He is one of the country’s cultural vanguards, having served as chairman of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) as well as one of the trustees of the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP). He is also an art collector, author, historian and newspaper columnist. But did you know that he is also a gardener?

“I’ve always been interested in gardening but never had the time,” he shares. “It’s something I inherited from my mother.” Laya’s “wild garden” is in an area that straddles both Panay and Quezon Avenues. The Japanese had dug trenches there during wartime. Most of the trees in the compound are 50 years old, some even older. Jimmy points out how unknowns have even sprouted (either lychee or longan). “I scatter fertilizer before the rainy season and a helper sweeps up leaves into compost pits — but otherwise the garden takes care of itself. Here, survival of the fittest is the norm. Ferns and other shade-loving plants thrive.”

The Layas moved from Dimasalang (left their beloved neighbors — a few relatives, a watchmaker, a racehorse jockey) and into the Q.C. area in 1955. Both of Jimmy’s parents were public school teachers (his dad Juan wrote a novel titled His Native Soil in 1941, and mom Silvina taught history). Jimmy has been staying in this particular house since 1967. He has seen the changes right outside his gate — malls and hotels sprouted, roads spread, greens gave way to more grays. “Panay palaka pa dati nun (laughs). Ngayon, sa buong area, eto na lang yata may mga puno eh.”

He shows me pieces of vintage narra furniture, comprising a sala set plus two rocking chairs. “My mother bought them at the Bilibid. Kasi occupational therapy nung mga preso nung araw ang gumawa ng mga ganito.”

Methinks one needs a catalogue to know the objects inside the house.

A divider is made of old barandilyas from a house that was to be torn down. A vintage aparador bears the sword-cut by a Japanese soldier searching for either valuables or incriminating documents. (“I’m not sure if it was really a Japanese or a Makapili,” he says, flashing a smile. “Andun pa ‘yung sibak.”) Jimmy remembers how his father built a makeshift air-raid shelter. “He stacked books upon books. It would have been disastrous kung nagkataon.”

Speaking of books, Jimmy’s house is a virtual library of vintage titles, out-of-print treasures, and most probably first editions. One even has a sheepskin cover and sheets made from Chinese rice paper. The tomes on painting, culture, business, genealogy are joined by paperbacks by Agatha Christie, Hercule Poirot and — Jimmy says so himself — Harry Potter.

He remembers, “When I was still studying in Stanford, I would go to secondhand bookstores during Saturdays and look for Filipiniana books and Philippine coins — travelling to San Jose, San Francisco, Monterey, Sacramento. I bought books for a dollar or two. I drove an old Ford which was purchased for $200.”

An árbol de la vida (a tree of life clay sculpture depicting Adam and Eve and God the Father in Paradise) was first spotted in then Yugoslavia, at the Belgrade apartment of Ambassador Leon Ma. Guerrero. Years later, Jimmy saw it at the Jo-Liza antique store. “Nasa floor lang. I bought it for a thousand pesos in the late ’80s.”

A vintage IBM typewriter was used by Dr. Laya in hammering out his accounting thesis at Stanford. “They typewriter runs on 110 volts, and someone anonymous (since no one admitted to the deed at that time) plugged it into 220-volt socket — so it’s been out of commission for close to 50 years. The last time I used it was for typing examination questions for my classes in UP.”

Laya shows me Carlos Valino’s portrait of the Layas which took 10 long years to be completed.

“Valino was very talkative. I was only free on Sundays, so he would come in at 9:30 a.m. and would start chatting. By lunchtime, he would have worked for — a total of — 30 minutes (laughs).” When the sessions began, Jimmy and his wife Alice only had one child. Then the second one was born. A few years later, they had another. The portrait still remained unfinished. Valino ingeniously repainted a handbag into the newborn.

“Our fourth child was on the way — so Valino had to finish the painting in a hurry (laughs).”

For the photo-shoot with Dr. Laya, photographer Geremy Pintolo and I agree to recreate the Valino family portrait: with books ensconced in shelves, light delicately reflected on the wooden floors, a window opening into a garden of leafy delights, the man in barong regarding the viewer magisterially — a constellation of curios behind him. But Jimmy is all by his lonesome now: his wife passed away in Baguio in 1990, and the kids have all left home to start their own families across seas and sectors on the map of the world — Madrid, the US and Singapore.

Dr. Jaime Laya never really feels alone. Where there are books, paintings, maps, memories and a life refined and refurbished by encounters with people, events and ideas, each day begins and ends like a tale — illuminating, enlightening, punctuated by birds and songs of lovelorn frogs.

Jimmy tells us he is meeting a seller of santos at 5 p.m. in Salcedo Village. He shares, “Nothing fantastic or rare, though. It is small San Bartolome made of wood.”

And Saint Bartholomew, by the way, is the patron saint of bookbinders.