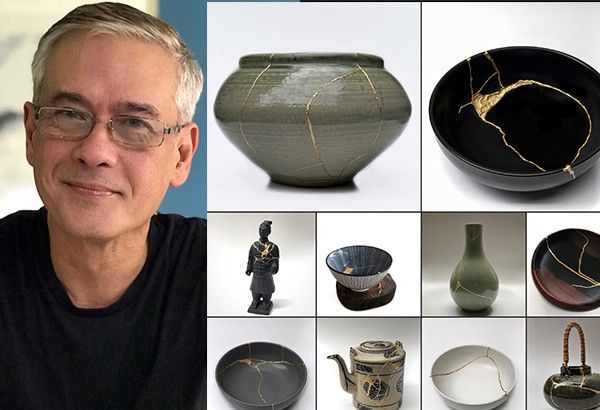

Unbroken: Raymond Lauchengco teaches modern Kintsugi art

MANILA, Philippines — When your favorite bowl, teapot, or any ceramic object falls to the ground and breaks into pieces, do you throw it away? Because it is no longer perfect, does it mean it is no longer useful?

There is an alternative: an ancient. Japanese practice that highlights and enhances the breaks with gold, thus adding value to the broken object. These restored objects have more value than before, because they become one-of-a-kind pieces that tell a story. What once could be seen as something to be discarded, now becomes something even more precious and valuable.

What is Kintsugi?

"Kin" means "gold" or "golden." Meanwhile, "Tsugi" means "rejoin" or "repair." So literally, "Kintsugi" translates to English as — "to repair with gold."

This traditional Japanese art uses a precious metal – liquid gold, liquid silver or lacquer dusted with powdered gold – to rejoin the pieces of a broken pottery item. Instead of making the item look “as good as new," Kintsugi highlights the "scars" as a part of the design. Every repaired piece is unique because of the randomness with which ceramics break and the irregular patterns formed. Because it emphasizes, not hides, the breaks, the result is more rare, beautiful and storied than the original, and honors the artifact’s unique history.

Kintsugi may have been invented in the 15th century, when Ashikaga Yoshimasa, a wealthy shogun, broke his favorite tea cup and sent it to China to get it repaired. Unfortunately at that time, objects were repaired with unsightly and impractical metal staples. So when the teacup was returned to the shogun looking like Frankenstein, he decided to try having local Japanese artisans repair it.

The local artisans decided to mend the cup as they would create jewelry, by filling its cracks with liquid gold, or lacquered resin and powdered gold. It can take months to repair precious ceramics using the Kintsugi technique, given the many different steps and the drying time required for each step.

“The Japanese art of Kintsugi teaches that broken objects are not something to hide but to display with pride.”

How my 'unbroken' story started

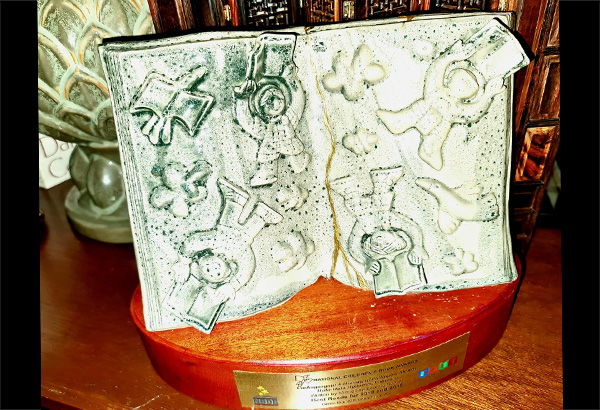

When the news came that I had received a second National Children’s Book Award, I was ecstatic. But when the messenger arrived, tired and sweaty, the piece, a heavy pottery work of art, slipped from his gloved hands and fell to the ground, where it broke into five separate pieces.

I was distraught, but the messenger was even more so. The gathered pieces sat on my table for a week.

By chance, by answered prayers, or perhaps by my eavesdropping phone, an announcement appeared on my Facebook feed for a class teaching a modern Kintsugi technique. The instructor was Raymond Lauchengco, a name I recognized from my youth — but as belonging to a famous pop singer! A little research revealed it was one and the very same person, and I happily enrolled.

Learning how to restore

At the beginning of the class, Raymond tells how he came across his unique take on Kintsugi: “I first heard about Kintsugi, the art of precious scars, from my church many years ago. And although I found it fascinating, restoring something I'd normally discard without a second thought, and highlighting it's imperfections to make it extraordinary, never appealed to me until l went through the year that was 2020. I can't think of anyone I know whose world wasn't turned upside down.

If it is true that art mirrors life, then I believe that Kintsugi could be a reflection of what it means to be human: how we all get pounded every now and then, how we all break, how we all have to pick up our broken pieces and deal with them so that we might find a way to be whole again. And while we can try to conceal the scars, a question begs to be asked — whatever for?

While I wanted to do things the traditional way, I had to find methods that would work [for the current times.] Melting gold, silver or platinum, or finding authentic 22k gold dust, and sourcing the authentic Urushi lacquer was not only prohibitive but difficult. I thought to myself — as much as I respect Kintsugi in its purest, truest form, there must be a way of taking its essence, which is about respect and continuity, seeing beauty in brokenness, celebrating imperfection, and make it accessible to more people in these very challenging times.

I studied books, articles, pored over photographs and videos. I broke a lot of things (my relatives thought I was crazy, and my wife did not approve of some of the things I broke). I experimented with different kinds of paint, adhesives, and fillers. I also came up with a method on how to best handle the paint brush so that minimal pressure can be applied to the stroke.

This is what I would like to teach you — how to do Kintsugi-style restoration by using modern materials that are easily obtainable and inexpensive, with ways that I have tried and tested.

Out of respect for traditional Kintsugi, I do not call my work Kintsugi. It is inspired by Kintsugi, but different. I call it Unbroken.”

And so, in that three-hour class, not only did we learn how to break a perfectly good ceramic bowl. We learned an engrossing, therapeutic, and satisfying way to put it back together. And indeed, I was more pleased with my amateurish attempts at modern Kintsugi than the original, unbroken bowl I had unwrapped.

My next project, of course, was to repair my award. It took me a couple of weeks, several do-overs, and many consultations with Raymond and my other Kintsugi obsessed friend Yorkie, to finally put its broken pieces back together and highlight its cracks to perfect imperfection.

But throughout the process, I realized the strong similarity to something else I was repairing — a personal circumstance that involved a lot of hurt, and which needed a lot of healing.

What I am 'unbreaking'

In a world that so often prizes youth, beauty, perfection, “the good life” and material excess, embracing the broken and battered may seem strange.

But everyone has places where they are broken. Our imperfections make us even more extraordinary. It is okay to be hurt and grieve; to be vulnerable. It is okay to accept the broken parts of us and allow us time to mend. Each and every piece of you can be put back together. But we have to do the work.

Just like two bowls, never break in the exact same way, so do our hearts, and so go our stories. Our broken places make us stronger and better than ever before. Our rewritten stories can be our gifts to the world.

Accepting and highlighting our scars

Whatever we are going through — a hurting relationship, the loss of a loved one, challenges to our health, financial troubles — the practice of fixing broken things may help heal what is broken in us.

Our hearts have golden cracks over it: some deep, some still in the process of healing. Our hardest challenges, deepest wounds and greatest fears have forever changed us. Embracing these can transform them into what is most beautiful, precious and admirable about us.

Things may fall apart. That’s life. But as you do the work, you will find that the most beautiful, meaningful parts of yourself are the ones that have been broken, mended and healed.

“Like the Japanese artisans who repaired the shogun’s bowl with gold long ago, let us see our imperfections as gifts to be worked with, not faults to be hidden."

Our cracks, hurts and struggles are what give us character. When sealed with the gold of acceptance, resilience and integrity, they trace our journey, and make us more unique and beautiful. Let them shine!

Raymond’s next Unbroken class is on March 26. For more information and to enroll, please visit https://www.sotruenaturals.com/.