Take it, shoot anyway: A review of ‘Not Visual Noise’

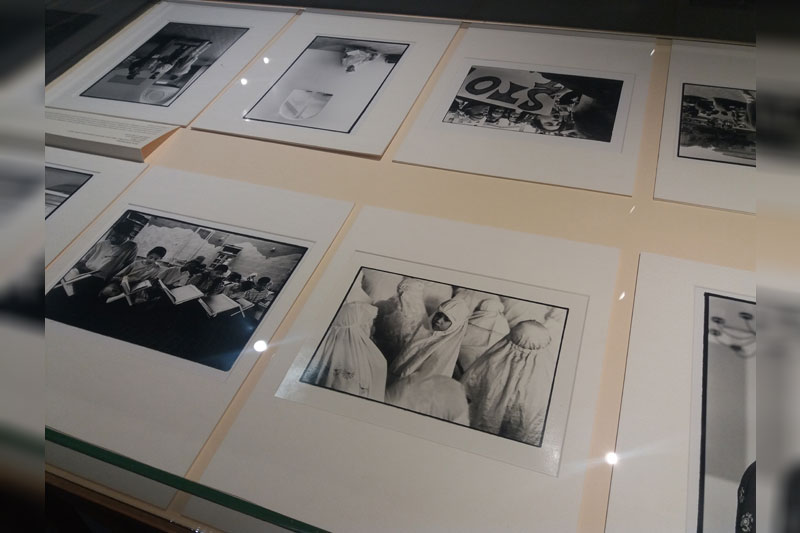

The Muslim-Americans living in the Bay Area in the early 2000s wrestled with riot and unrest, but in Rick Rocamora’s black-and-white photographs, they inhabit a space that is volatile in its silence. In some images, subjects are within or against rectangles or enclosed shapes, contained or stationed within fixed units of space. This compression continues even as the subject is placed amid patterns: a boy turns, revealing an individual face in a repetition of white hijabs; children read the Koran, appearing as repeated X’s barring them in. These photographs almost translate conflict as containment, which spills over to how this section was curated: in a uniform arrangement of rectangles, on a table encased in glass. This uncanny stasis also imposes silence to the woman photographed during a protest with her face behind a picket sign. Instead of noise, we imagine her open mouth as a howl that is void of sound.

Rocamora’s series called “Freedom and Fear: Bay Area Muslim-Americans after 9/11” is among the first that introduce us to “Not Visual Noise,” a survey exhibition curated by Angel Velasco Shaw. The intention is to “showcase the scope of Philippine photography from the latter part of the 20th century to present day.” These images were not typically exhibited together because they “were seen as too divergent.”

As final products, photographs are generally stubborn; they tend to deflect attention from themselves, and instead act as windows to something else. Walking, we shuttle in and out of times and places, in and out of anxieties and dreams. Shaw’s way of mounting, however, with its exciting play of materials, keep us bound to the here and now, to the moment of looking. Usually seen as only ally to message, here the forms already arrest and articulate.

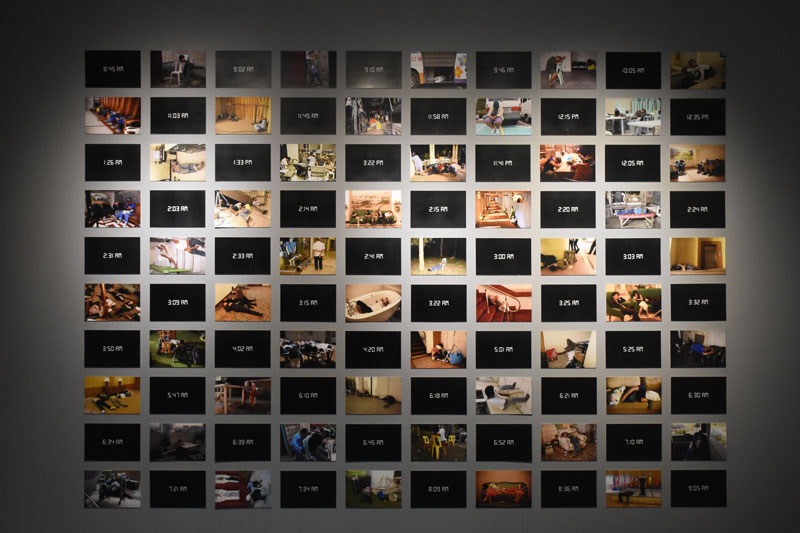

Boy Yniguez’s 1985 photographs of the Berlin U-Bahn 1 subway hang side by side on lightweight chains. Taken from a uniform angle, arranged chronologically, the slow succession suggests surveillance within linear, monotonous time. Passengers stream in, fall asleep. Shaw’s curation gets us to walk and watch, immersing us in states of waiting and anticipating. What is about to happen? Who is about to show up? It invests the routinary with some suspense — only to lead us back to another station, another destination, another every day. The consequence of banal time is further mined in the work of Neil Daza, placed far from Yniguez and aptly titled, “Who Ever Said that One Shooting Day is 24-hours”? Aligned in a grid, photographs referring to unjust working hours in film and TV measure the hard toll of small minutes.

The linear arrangement is potent and disquieting in Carlo Gabuco’s “The Other Side of Town.” Between framed images, empty spaces carry QR codes leading to recordings of sitters’ stories. Like Rocamora’s, Gabuco’s photos give conflict a human face, while these black spaces also appear to acknowledge a presence that is missing or lost.

Less concerned with the boundary between genres, the exhibition shows photographers moving in between and across. It hints at how they contend with the honor and the burden foist upon them by the profession, or by a medium whose own burden has been to represent. A number of photojournalists, scattered across space, are on the heels of history unfolding, while others snap personal struggles and private encounters. I was reminded of a conversation with photographer Geloy Concepcion in 2017, when he talked about the necessity of micro-stories. In a climate of conflict that imposes all kinds of invisibility and disappearance, Concepcion argued for the particular power of individual memory, of locating the human in the absence of the humane. Concepcion’s “Sanctuario” thus places the viewer in intimate contexts: his wife Bea cradles their daughter Narra in golden light; a lady, wrinkled with age, isn’t ready to see herself photographed, but tells him “take it!” Shoot anyway. This command to take and shoot is a persistent, celebratory proposition that endures throughout the show.

There are many more sections that deserve to be written. For that, “Not Visual Noise” is generous and exciting; it gives photography the space and attention it’s due. Yet with the breadth of this undertaking, it remains the viewer’s task to contend with an overwhelming divergence. As I view, I wonder about the risk of emphasizing the photographer’s practice rather than the photographed, of treating subject matter as somewhat secondary, submissive to the curatorial intent of showing how rather than what. While it gives context to some, I feel greatly uneasy viewing, for instance, Carlo Gabuco’s disquieting portraits so near Nap Jamir’s compelling explorations of a photograph’s materiality, or Emmanuel Tolentino Santos’ “Holocaust” series that is heavy yet hard to process with a lack of context. How do we process and deepen the weight of these issues when juxtapositions have a tendency to dilute? I’m well aware that a cold, hard gaze is required of a critic, one that treats photographs as photographs and not the issues they represent. Yet it is exactly this detached gaze that afflicts our era and urges us to forego empathy in favor of objectivity, to scroll over the dead for they are only content. The show must be seen by anyone wanting to do, show, or curate photography, yet it leaves me wondering, how can a large-scale exhibition be much more than a snapshot of its time?

* * *

“Not Visual Noise” will run until March 29 at the Arete, Ateneo de Manila University.