Footnote to a lost bohemia

Ermita was the first magazine I read literally cover to cover as a teenager in the mid-’70s, all 10 issues of 1976, till I fell asleep with it in my basement room in UP Village, its stories, poems, articles possibly taking root in my subconscious. It was cult reading for a repressed hipster during martial law, and needless to say opened a door to our rambling youth.

It was in the maiden issue where I read Sylvia Mayuga’s ‘Love Never Gives Up On Avenida,’ a template for the blind musician on that avenue, full of romance and longing, whose music can still be heard on the walkways and bridges between stations, although the lone armless minstrel by the Sta. Cruz church off Carriedo has long gone, along with his rusty makeshift harmonica and can of evaporada for stray coins.

I tried to contribute to the magazine a small essay in the manner of Ermita’s Evergreen Review style, something about twilight dreams during those dropout years in Diliman, but never made it, though it did eventually get printed in Jingle magazine’s These Pages Tell A Story section a year or two later, a sad footnote to nightfall on campus where the corridors seemed to disappear in impasto, the blackboards fading to black amid the deafening sound of crickets.

Was able to talk with Sylvia over the phone when she still stayed in an apartment on Malingap Street, Teachers Village, and in smoky voice she broached the idea of putting up a students’ section in the magazine, which however was about to close shop at the time.

Her younger sister Christy I heard sing with the jazz band Feathers at the DZRJ parking lot concerts also in the same decade, our version of Flora Purim along with Anita Celdran of the band Mother Earth.

In the quarterly literary journal Manila Review edited by Greg Brillantes, a short story by Alfred Yuson came out, ‘Romance and Faith on Mount Banahaw,’ accompanied by illustrations by possibly Red Mansueto or Juanito Sy, including one of a woman I imagined must have resembled the elder Mayuga. If a drawing could etch itself in one’s memory then that certainly did, another template for venturing into the mystic.

Long blank years followed, then sometime in the ’80s dropped by her apartment on A. Roces Ave. in Quezon City, the same street where Midweek magazine was located, and nearby the refurbished post-EDSA revolt Manila Times. I was with then Midweek art director Alan Rivera, also since departed, and she was with another Ermita staff writer Elizabeth Reyes. It was October right around her birthday, and the place had the smell of kretek cigarettes.

A copy of her first book, Spy in My Own Country which includes “Love Never Gives Up,” I purchased at a bookshop off Session Road in Baguio City during one of those out of town jaunts of romance and faith with the partner, whose face I imagined resembled a drawing by Red Mansueto.

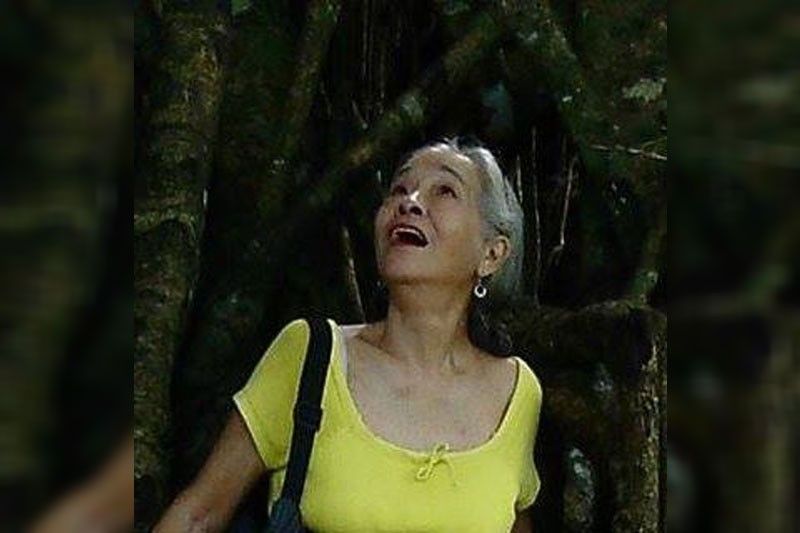

Another long period of hiatus followed, then in the 2000s she began writing for the online edition of this newspaper, little did we know she was already a doting lola.

At the National Book Awards which she regularly won whenever she had a book out, she sometimes attended the ceremonies with granddaughter in tow, they made quite a pair and a sight for sore eyes.

She called up the office once to ask if she could use an essay that came out in this column; they were putting together a tribute book for the late incendiary cartoonist Nonoy Marcelo.

On rare occasions she would foray from her ermitaña’s cave south of Manila, and wind up in her old haunts of Malate, this time at the Oarhouse, on the selfsame street where the old magazine was located although now since dissected by a mall. She sat at a table with Peggy Bose, the artist Santi’s widow, and she called the proprietor “guru!” as different viands came out of the kitchen and onto our table for sampling.

At the wake of another ermitaño, Jose Victor Penaranda in 2017, she remarked tongue half in cheek how I was beginning to resemble another of the magazine’s staff writers, a common friend now residing in Dumaguete City.

At her own wake earlier this year, I read a poem on the tagabulag, a not-exactly sinister apparition that blindsides our perception of things, and a poem by Galway Kinnell, “Daybreak,” how starfish sink into the sand at sunset, disappearing like the real stars at daybreak.

Days after her interment, comes an e-invite from Ermita’s reclusive former publisher about a forthcoming music and arts festival in Sagada, the talismanic place I first read about in the magazine of our lost bohemia.