Tropical dreaming

MANILA, Philippines — No two artists paint a landscape in the same way. It’s clear in the exhibition “In Harmony With Nature” which opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila (MET) last Sept. 28. The show is the result of a Filipino-Chinese exchange program which is spearheaded by the Bank of China Manila, in partnership with the MET, the Chinese Culture and Art Association, and the China Daily Asia Pacific. The five selected Chinese artists, from different cities across the whole of China, spent three days in Palawan. It’s a historically resonant location for being part of the trade route of Chinese merchants crossing the West Philippine Sea, past the Kalayaan Islands, in search of pearls from the Philippines.

The show’s opening at the MET was attended by Filipinos and Chinese alike. The exhibition space was halved, with the five Filipino artists’ works on one side, and the Chinese works on the other, which highlighted the differences in style and approach. It’s expected considering that all of the artists involved have long-established practices in their respective countries.

Bukuk Chai acknowledged the Philippine setting of the residency by grafting Filipino iconography onto typically Oriental scenery such as the carabao and a rooster in a forest of bamboo, and a morena woman submerged in a pool of tropical fish. On the other hand, Manuel Baldemor’s works of like “Mga Ibon sa Umaga (Early Birds)” depict the craggy cliffs of Palawan in a manner akin to the ink paintings of Zhixin Cai’s “High as Mountains and Long as Rivers” and Jie Ding’s “The Terraces Surrounded by Clouds.” Interestingly, Baldemor opted to suspend the canvas vertically in the traditional manner of Chinese scroll paintings, while Zhixin’s and Jie’s works were framed.

Like Rico Lascano’s Zen-influenced abstract paintings, there were Filipino works that seemed to adapt to Chinese aesthetics and forms. However, the opposite cannot be said. The other Chinese artists depicted landscapes elsewhere, like She Liu’s sketches of empty Kyoto suburbia and Zhixin Cai’s Yangtze River landscapes. One is left to wonder how the artists’ residency in Palawan influenced the subjects they depict. But then again, a residency elsewhere is not necessarily a mandate to literally depict what is present; but a change in surroundings can also prompt reminders of one’s own origin.

All in all, the landscapes depicted are pristine and idyllic. The industrial interventions made by humankind are curiously absent from most of the works, save for small figures and huts in the distance. The repurposed windows-turned-canvases of Phyllis Zaballero that depicted the same domestic view out a window was the closest to a human presence, with still-life objects remaining as evidence.

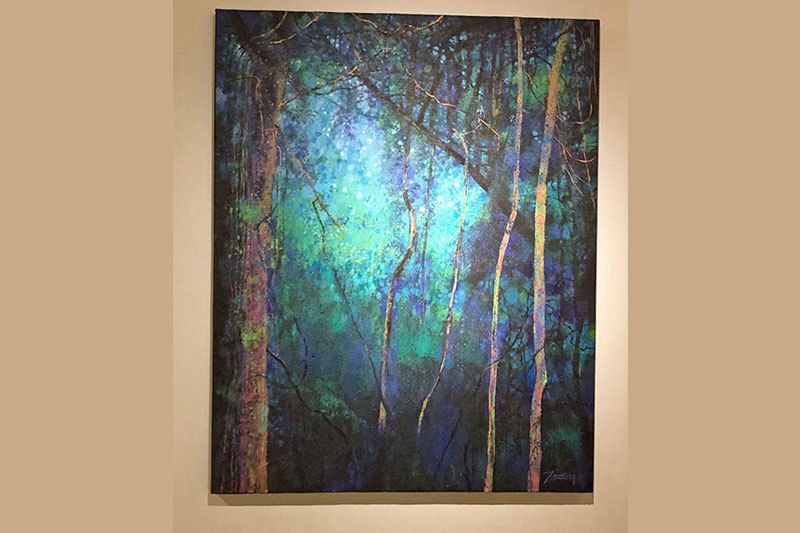

The dialogue between the works was more about parallel monologues rather than a conversation, in which these picturesque landscapes become a vehicle of nostalgia for a time when the climate crisis wasn’t an impending concern. Jonahmar Salvosa’s “Zigzag Forest” returned to his childhood memories’ lush green woods in Camarines Sur, which is threatened by deforestation left unchecked. How much time is left for these blissful daydreams, while global warming, industrialization, and extinguished ecosystems endanger the very landscapes depicted?

Interestingly, “In Harmony With Nature” contrasts with the MET’s concurrent exhibition of the Philippine Pavilion of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale: “The City Who Had Two Navels,” which confronts these assumptions about whom and what ends development benefits. The conversation of environmental sustainability is inherently tied to humankind recognizing its impact on nature, and acting upon the urgent need to protect it--of which every individual, institution, and government play a part.

The stated intention of “In Harmony With Nature” was to promote “environmental stewardship and green living” through bridging two countries’ perspectives. Yet the unrelenting variables here are our cultural specificities and nuances about what the harmony truly means in execution. The varied interpretations amongst the Filipino and Chinese artworks have yet to reach a unified conclusion, but that’s not necessarily to the detriment of the larger conversation.

More than establishing similarities, one must recognize the unique circumstances that communities face. Even definitions of development can vary across a hyperlocal setting. Without this mutual acknowledgment, harmony remains an abstract notion detached from reality. Within the confines of this exhibition space, confronting the root of the problem remains the elephant in the room.