Social realism’s second birthing

With Philippine Social Realists by Amadis Ma. Guerrero, launched late August at the Erehwon Center for the Arts in Quezon City, the art movement as we know it locally comes full circle, after Alice Guillermo’s Social Realism in the Philippines also published by Erehwon decades ago. And while the usual suspects may be present, there are a number of notable additions, fresh blood as we call it, to ensure the fire keeps burning for years to come, and make proud the late critic Guillermo to whom the book is dedicated.

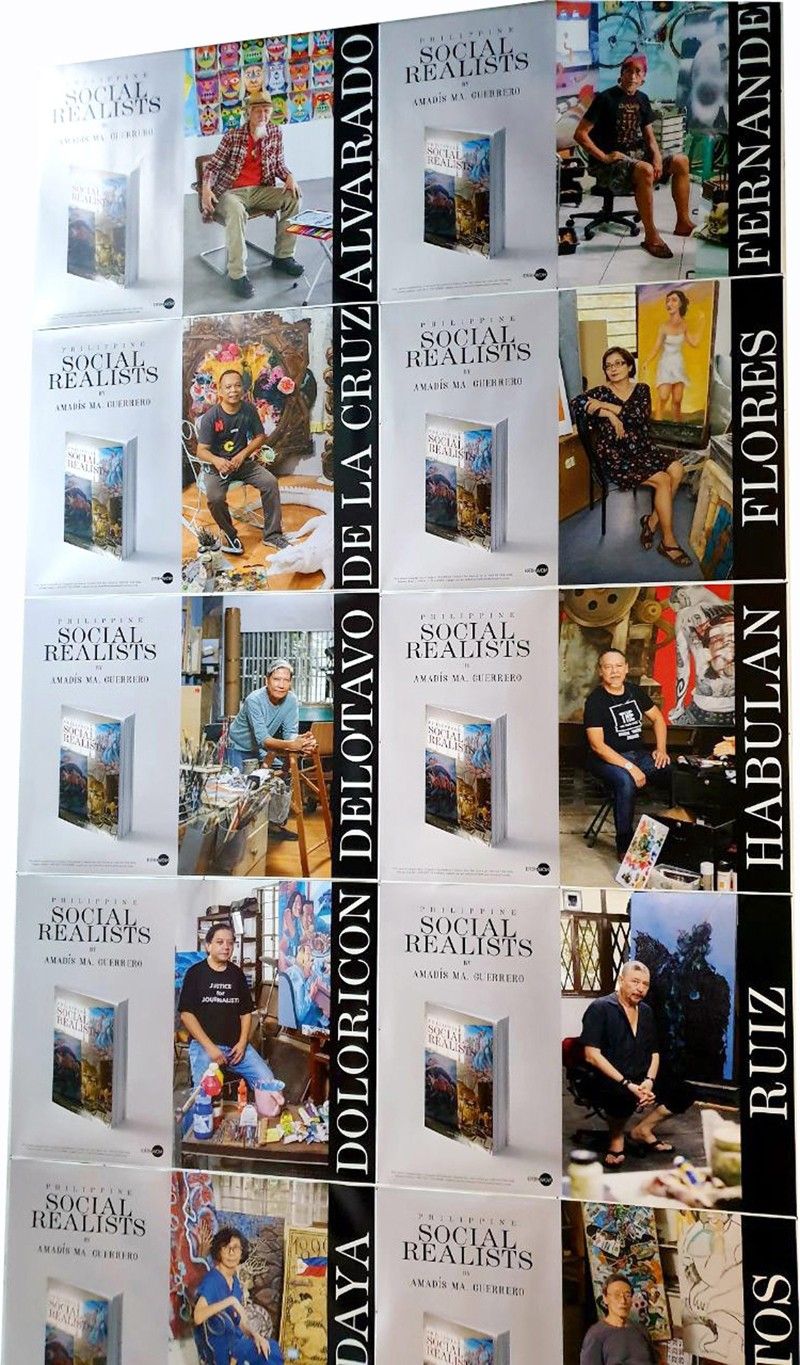

So while we have Pablo Baen Santos, Antipas Delotavo, Edgar Talusan Fernandez, Neil Doloricon and Jose Tence Ruiz, fixtures all at the annual fiesta at the art hub in Old Balara and whose sample works are part of the gallery’s permanent collection, also present are the younger Karen Ocampo Flores and Demetrio de la Cruz, and the roving, spirited likes of Renato Habulan, Imelda Cajipe Endaya and Nunelucio Alvarado. That’s 10 of the most accomplished artists of any school known to plant or animal, and certainly quite a spread. Guerrero makes sure we get to know each of their back stories, their forebears and initial forays into art, major exhibitions and such accompanied by representative works given ample space in the coffee table book.

Guerrero will be first to admit that he’s no art critic, but more a master of reportage, which he puts to good use in this series of portraits of the artist as Philippine social realist, with interviews conducted as late as last summer. Occasionally he may insert snippets of his own storied family history as an aside or parallel commentary, but we forgive him his vendaval; he never loses sight of the subject at hand.

Flores, granddaughter of the fabled national artist HR, had one of her first exhibits in Pinaglabanan Galleries in San Juan in the late 1980s, part of an all-girl group show consisting of students of the late great Chabet, and that early she had lambent takes on the female body if not anatomy, although not really a grim and determined social realist at the time, and neither is she now. There has always been a wistfulness to her work, as if the swaying of grandpa’s dancers were a pentimento.

Yet her paintings have since taken a more socially conscious bent, as evidenced in her participation in the Tutok collaborative shows from the now-shuttered Brittania art gallery in Cubao to the lab fest jams on Escolta.

Though this is the first time we’re seeing the work of the likely group bunso De la Cruz up close, we’ve heard his name bandied about, perhaps as one of the more promising artists to watch out for. Well, he hardly has time to disappoint in his paintings that deliver us from gin, and trespass into our inherent desire for designer goods with a load of enlightening bull. Like the rest, he, too, grew up poor; and like the others, too, art was as much a way out of poverty as a means of self-expression.

Alvarado never really struck me as a social realist, with his series of masks and face paintings exhibited years back at the Oarhouse in Malate, which work had a lasting impression and influence on his fellow artists from Negros. Only upon coming across his painting of sacadas waiting for their envelope on payday do we get to understand why he belongs here. Yet Nune has largely been chameleon-like, now you see him now you don’t sa punso, and his is the most memorable quote in the book: you can’t be clenching your fist all the time. Could also be directed at photo opportunists and buffoons in government.

Another gray area is Cajipe Endaya, whose early work undoubtedly espoused the feminine principle. Her “Ang Balabal” from the ‘80s is a simple pen-and-ink line drawing of a female figure, back view, holding a shawl before a closed door. Must have grown by leaps and bounds since, even if basic ground remains a subtle feminism, as in “Brides Against the Macho” that recalls endless Russian dolls one inside the other, as well as another installation of the overseas worker as domestic helper: an assemblage of suitcase, plaster statue, plaster bonded papier mache, mop, broom and other found objects.

Tence Ruiz and Doloricon, both well known for their editorial cartoons and illustrations in newspapers and magazines, show a more adept, deliberate style in their paintings, but not departing too much from the milieu of journalism and its fetish for the current. Tence, in fact, has branched out into performance and large-scale installations, while Doloricon continues to balance the worlds of academe and newsroom.

Delotavo and Baen have been known to jam with Erehwon musicians during events in the Old Balara watering hole, Habulan has become elder statesman of a growing community of creatives, while Fernandez reflects on different planes of himself in a barbershop.

Alice may not live here anymore, but it’s a gift really to be able to drop that stupid fist bump once in a while and let press releases go hang.