Paronomasia and punditry in poetry

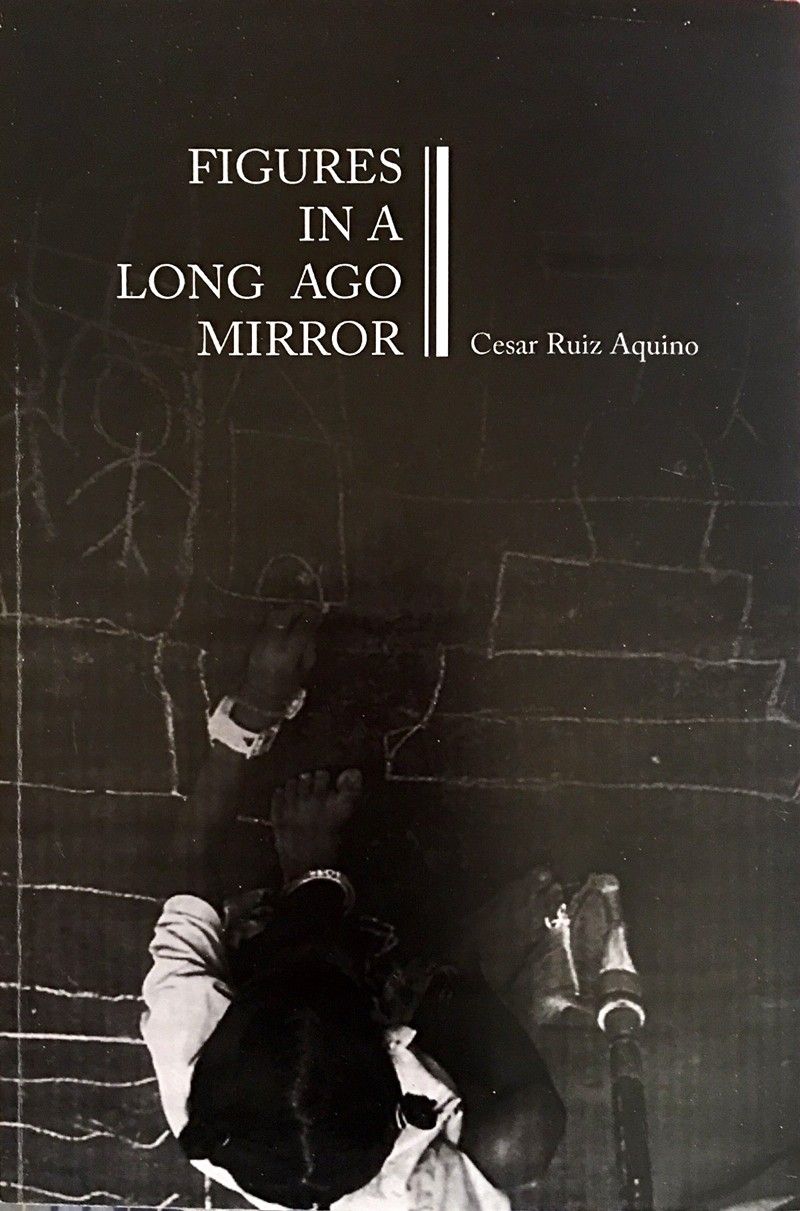

Figures in a Long Ago Mirror by Cesar Ruiz Aquino, published by Silliman University, is either the poet’s sixth or eighth poetry collection, depending on whether manuscript completion or actual publication serves as the basis. Aquino has two other, earlier manuscripts still in the publication pipeline.

Honored to be the first book ever published by the university where he has taught literature and creative writing for decades, apart from serving as a resident panelist in the annual Silliman University National Writers Workshop (SUNWW), this one puts together 101 poems, a majority appearing as brief, engaging flirtations a la Twitter.

The poet can’t help but indulge in paronomasia, “a form of word play that exploits multiple meanings of a term, or of similar-sounding words, for an intended humorous or rhetorical effect.” In a word, puns.

Infinitely versatile with his homophones and metonyms, he is also a certified pundit, someone who dispenses opinions in an authoritative manner, or a scholar on a particular subject area. The word comes from the Hindi pandit, derived from the Sanskrit pandita: “a learned man.”

Tsundoku has never been a problem with this Dumaguete sage everyone hails and salutes as Dr. Sawi. All the books that come within any hairbreadth of possession have been perused, some repeatedly, with powers of retention often dazzlingly displayed at writers’ workshops, where he cites this and that author or title, quoting lines across centuries. This knowledge is inclusive of arcana, with the ludic facility never at arm’s length, nay, not even an ant’s distance.

Gamesmanship with words turns pandemic. For he is the Pan who hasn’t been slowed down by the Peter principle, the Pan that is the Greek god of the wild, companion of nymphs, and who looks similar to a faun or satyr, often associated with sexuality.

Aquino’s poems and stories have won him Palanca and other prizes, among these, quite recently, the Philippines Graphic magazine’s Poet of the Year accolade.

Here’s the title poem in full: “We entered the place, everyone a self-centered/ stranger to the people inside as well as to each other/ yet often like a gang of ten, all young./ She took a chair in the same row as mine, with an air/ all her own, all smiles, all smile like the rest while/ being different, who wouldn’t be/ with that beauty? Would-be beau/ was quick as light to crack a joke,/ a maneuver to sit opposite her;/ I kept to the mirror beyond, behind him, or/ should I say to my own luck, kept looking,/ and true enough, and not at all half-way,/ our eyes met likewise — no, otherwise:/ For the first time, in the oddest, may I add,/ happiest of days, so happy whatever would happen next,/ not to mock, was anti-climactic.”

Poems that dredge up the distant past are what allow the poet to flex lyrical muscle memory. They are so much richer in the application of extended line and narrative, far from the calisthenics or give-away brevities that impressionistically engage in a swift snatch of the moment.

An example is “Late Night Chat With A Girl”: “‘Write you in my dreams,’/ I lined (very likely lied)./ But where else really?”

Another is “Perhaps”: “Van Gogh didn’t know/ He possessed, like it or not,/ An ear for color.”

The additive that is metaphysical gravitas attends “The Interpretation of a Dream I”: “It wasn’t a bow or a lyre/ or a birdcage in my hand, yet/ it semed all three together let/ go, and the stillness flew the air.”

These quickie poems may be nightly itches scratched during the somnambulistic creative process, as the poet imaginably continues to wade forward with his announced anti-novel that’s already taken up hundreds of pages, but still seeks errant to erudite directions.

They are breathers that may be recognized as tokens of arabesque design, taking florid moments captive for condensation, if lightly, as gestural workouts. Maybe they’re meant to eventually help buttress the topographic gothic or quake baroque cathedral in the making.

Playing with form is a customary feature, so that there are haiku, tanka, sonnets, blues, a sestina, a kalisud, verse literations, a “One-line Ekphrasis,” “Five-Vowel Poetics,” “The Koan of Kuan,” “Cebuano Latin,” etc. Frequent literary references serve as public curtseys to influences such as Edith Tiempo, Kipling, John Donne, Dante, Dylan, Borges, J.C. Powys, Graves, Somerset (Maugham), Coleridge, Goethe, Villa, Apollinaire, Hart Crane, A.E. Housman, apart from many local poet-friends.

No collection from Aquino comes without a revised work, sometimes on its nth iteration. Here there are three: “She Comes With Horns & Tail,” “Blue God” (“a poem originally intended as a novel”), and the lengthy “Eyoter” — which goes on in quatrains for 13 pages.

At almost 300 lines, it ends thus: “Me, I may never see Finland,/ Iceland, Ireland, Greenland/ let alone a world in a grain of sand./ But to see a grain of sand in the world// why, that’s just as awesome/ I owe you some!/ I’ll drink to that & eat/ my heart out// Cesar Aquino in pun y vino/ in Dumas Goethe/ Where every love must end, a tale/ told by T.S. Saluyot// This is the way the ruba ends:/ He kisses a girl from head to foot/ & the end of his exploring/ will be to arrive at where he started”