The first Zobel and the last Botong star at the León Gallery Auction

The Fernando Zobel that started it all — the artist’s first-ever oil painting by his own handwritten account — and the last Botong Francisco recorded before his unexpected death are just two of the exciting highlights at the León Gallery Spectacular Mid-Year Auction this June 22.

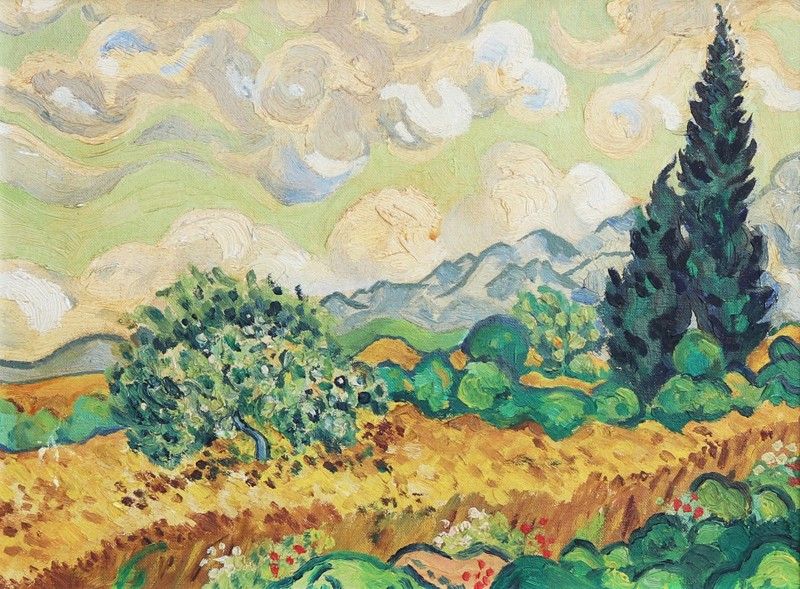

Fernando Zobel would write a close friend’s mother, L.L. Rocke, on Feb. 3, 1972, about this work. “As you probably know, it is the first (underscore supplied by Zobel) oil painting I ever did (and) is a copy of Van Gogh.”

Zobel and Van Gogh were as diametrically opposite as they come: Fernando Zobel was born into a wealthy and influential family; his father was the industrialist Enrique Zobel. Vincent Van Gogh’s father was an austere minister and his family, as he did, struggled. Zobel would graduate from Harvard University; Van Gogh, on the other hand, did not even complete secondary school.

The first Fernando Zobel, an homage to Van Gogh’s “Wheatfield with Cypresses”

Zobel would have seen Van Gogh’s “Wheatfields with Cypresses” in the flesh at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Dated July 1889, it is one of three works in his “Wheatfields” series. (The two others are at the National Gallery of London and a smaller one is in private hands.)

Of the time when Zobel would have painted his version of this famous work, Harvard Magazine wrote in 2009, “In Cambridge in 1946, Zóbel stood out as a well-to-do student among veterans attending on the G.I. Bill. But becoming a regular at the private Fox Club did not interfere with his art studies or hard work in history and literature. He wrote a senior thesis on the plays of Federico García Lorca (then banned in Spain) and graduated magna cum laude in three years.”

Thus the undulating blue skies and bold yellow fields demonstrate a young man’s optimism as well as idealism, a completely different worldview from the sufferings of Van Gogh.

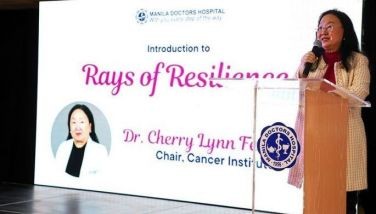

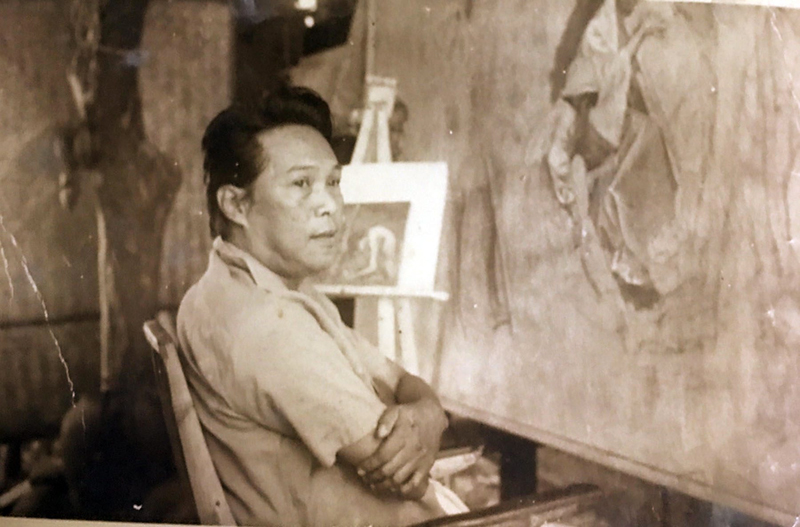

Botong Francisco with a study for “Camote Diggers” on the easel

The second masterpiece at the upcoming auction is by Carlos “Botong” Francisco who was known as the poet of Angono. He was also the architect of the Filipino soul. He would also find inspiration in Van Gogh’s works in this quest.

Botong was in constant search of heroic Filipino iconography. The warriors of the northern and southern tribes; the mythical kings and mythic heroes: Lapu-Lapu and Jose Rizal; Rajah Sulayman and Princess Urduja. In the Philippines’ mid-century, he would create mural after mural that celebrated these characters.

And yet, one of Botong’s first paintings was “Kaingin,” which, in 1945, told the visual story of the grindingly poor homesteaders who had survived World War II, but not by much. The next one, created a year later, was called “Camote Eaters” after Van Gogh’s “Potato Eaters.”

Van Gogh’s painting captured the desolate difficulty of country life, so he gave the peasants bony faces and hands. He wanted to reflect in this way that they “have tilled the earth themselves with the hands they are putting in the dish... that they have thus honestly earned their food.”

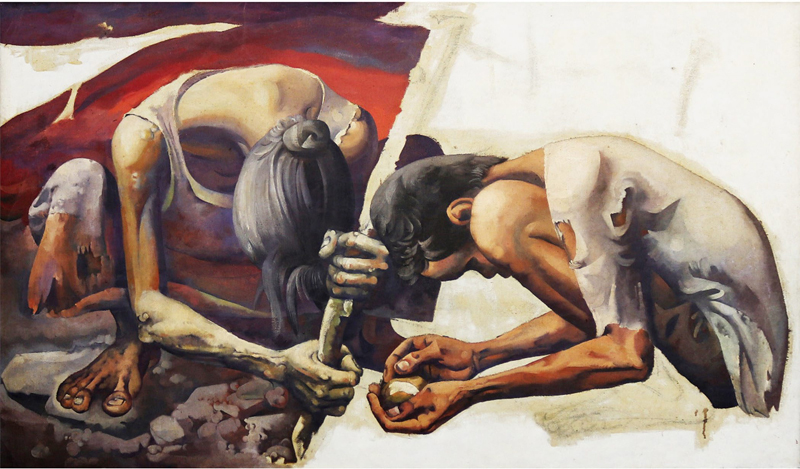

The last Botong: “Camote Diggers”

Strikingly, Botong’s last painting was the “Camote Diggers,” unfinished before his untimely death. It shows a white-haired grandmother with her grandchild — demonstrating how poverty can span several generations. They are bowed by hardship, their hands and feet gnarled by hunger, their backs broken by life.

Botong comes full circle in his odyssey to capture the Filipino everyman, no less heroic but always honest and authentic.

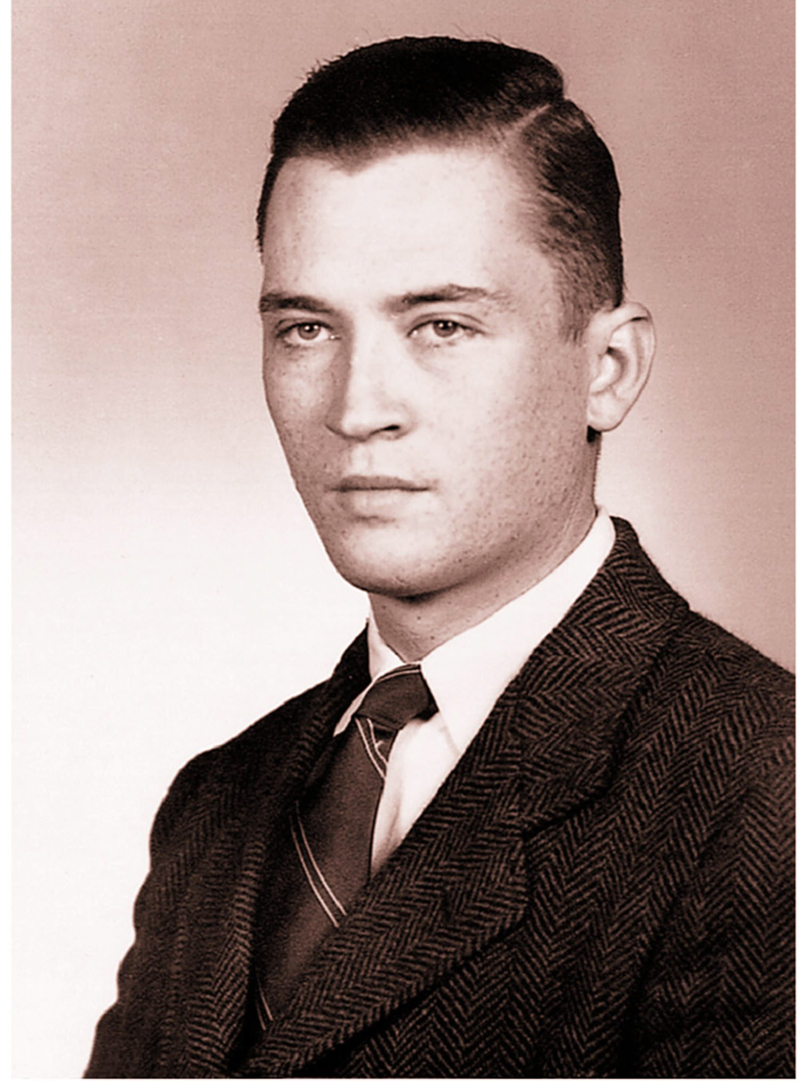

Another important piece is by Lee Aguinaldo. The eldest son of the eldest son, Aguinaldo was born into a commercial dynasty with high expectations of him. His grandfather was Leopoldo Aguinaldo who was dubbed “the Merchant King” and founded the Aguinaldo’s department store and furniture manufacturing firm. His father, Daniel, expanded the family’s interests into lumber and pearl cultivation.

Trained at a US military academy (his mother was American) and at a local business school, he did not receive formal training in the arts and was largely self-taught, as a result of his father’s disapproval of what was regarded at the time as a non-serious profession.

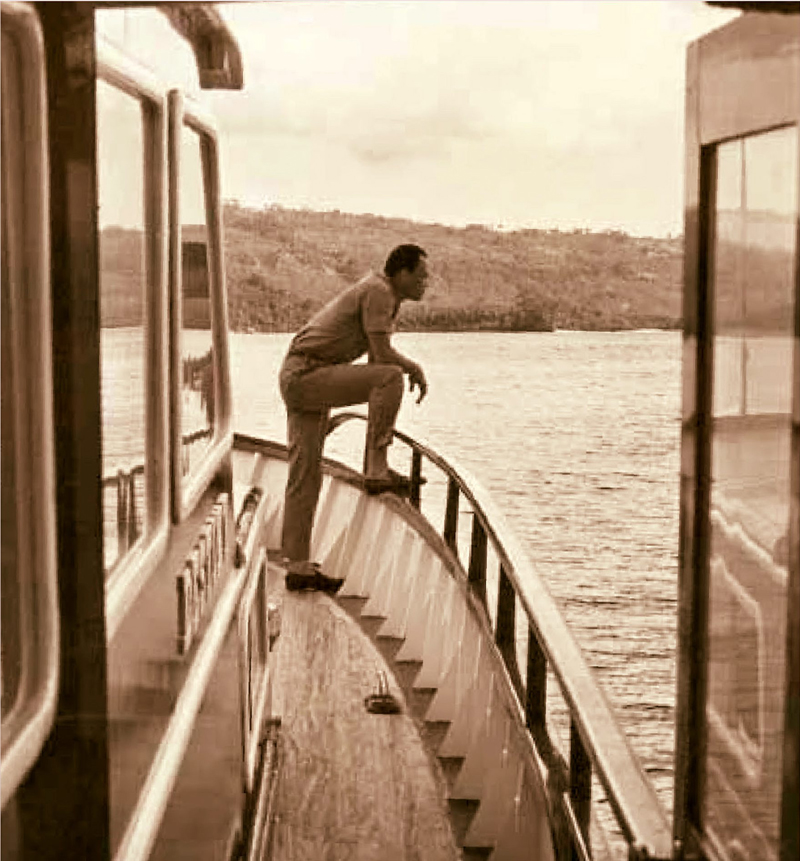

Lee Aguinaldo and the sea

He found a kindred spirit in Fernando Zóbel who was himself leading a double life — with one foot in the corporate world of Ayala y Cia and the other in the exciting terrain of the local art scene. Zóbel soon took him under his wing and Aguinaldo, at just 19, joined his first group exhibition at the Philippine Art Gallery.

The following year, at age 20, Lee Aguinaldo was selected to join Magtanggul Asa’s landmark show, “The First Exhibition of Non-Objective Art in Tagal,” also at the Philippine Art Gallery. He contributed three works and was also singled out for lavish praise. (There were no illustrations of his work as Asa insisted that black and white would “not do them justice.”)

A Lee Aguinaldo creates gorgeous visual counterpoint to these two masterpieces. Titled “All Blue No. 3,” and painted in 1992, it expresses Aguinaldo’s own artistic journey.