Exciting new poetry, in Cebuano and English

During the first week of the Silliman University National Writers Workshop in Dumaguete, a discussion led by National Artist for Literature Resil B. Mojarers and Simeon Dumdum on the “balak” or Cebuano poetry led to a wonderful discovery.

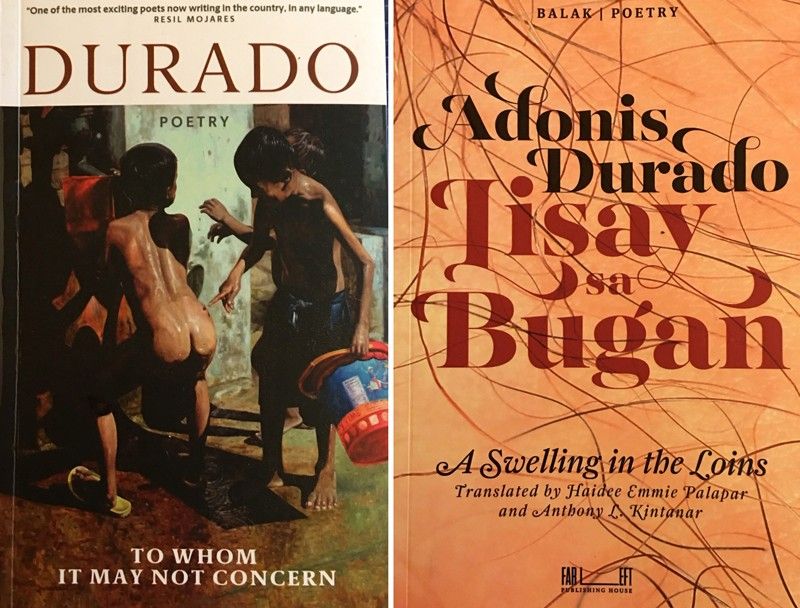

Mojares had shown a book by a young Cebuano poet, Adonis Durado, titled Pahinungod sa di Hintungdan in one of its covers, and To Whom It May Concern in the other.

There was no back cover, as it was a bilingual collection by virtue of translation. The English half begins with its own title page and proceeds to page 87, following which an unnumbered page where the translators are listed serves as the midway border before one has to turn the book upside down, and meet another page 87, which has the final poem in the original Cebuano.

Other than this innovation, the book is ingeniously designed, with some poems presented in inimitable graphic fashion — with drawings, comics strips with exposition and dialogue balloons, special see-through onionskin pages, and various other novel design and image features, including having a poem titled “Google Earth” appearing as separate single lines within white strips dispersed around a Google map.

One of the lines reads: “This is the lot we pawned when my wife underwent chemotherapy.” Others are “This bridge where pops was murdered” and “The boarding house where I shagged Cherie.”

I was sufficiently intrigued after borrowing the book from Resil to check out its contents. He assured me that he’d send me a copy.

Mojares’ blurb reads: “Adonis Durado’s poetry glories in the richness of the folk and popular speech — earthy and playful, reckless and disciplined, vulgar and sly, comic and (as in all good comics) subversive. But it is also poetry that is vitally current and global. Imagine Yoyoy Villame reborn as a poet and graphic artist who fancies de Chirico and Magritte and reads Derrida and Szymborska. Durado is one of the most exciting poets now writing in the country, in any language.”

The copy came soon enough, with another, earlier collection, titled Lisay sa Bugan / A Sweling in the Loins (2016), translated by Haidee Emmie Palapar and Anthony L. Kintanar, with a Foreword by Marjorie Evasco in both Cebuano and English. Both were from Far Left Publishing House, with the latter book coming out in 2017, with Marvi Gil, Gerard Pareja, Noel Villaflor, and Jeremiah Bondoc serving as its consummate translators.

From the book: “Adonis Durado is the author of three previous poetry collections. He was the recipient of several literary awards, including the Lacaba Prize for Cebuano Poetry (awarded by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts) and the Outstanding New Writer Award (Cebuano Studies Center). A visual journalist by profession, Durado received the Knight Journalism Fellowship to pursue a graduate study at Ohio University (USA) starting Fall of 2017.”

To Who It May Not Concern is divided into 4 sections with 15 poems each: “For the Faithless”; “For the Speechless”; “For the Humorless”; and “For the Worthless.”

Besides its novelty of design, inclusive of the use of a Rorshach inkblot test and a polygraph machine chart, a myriad of references — to Wittgenstein, Greek philosophers, other poets and writers — suggest indefatigable reading habits. Durado also frequently offers whimsical ars poetica forays, where the poem is likened to kung fu or a pet chick, or attributed to lion and tigers, with other fauna like a bird, a pig, an egret, a buffalo, figuring in the marvelous equations.

Throughout the collection, the poet-persona triumphs with his ludic command, his playful spirit laying on a dominant chord.

Here’s a sample in full: “Poetrickery”: “poetry is not just/ about the facts/ what then if it/ mentions your name/ or the date today/ or the debts which/ are still unpaid/ sometimes it must/ utter untruths/ must be envious/ must detest disguise/ must at times tip/ the scales of disbelief/ such is the poetic/ justice in life/ that the creditor/ curses your name/ and you return/ home that night/ wasted and wounded/ while your pregnant/ live-in partner ripens/ at the window/ of the promise of/ the ocean of promises”

Rich imagery enhances the ribaldry, while metaphors are as fecund as they are graphic, as in this excerpt from “Guffaw in silence”: “… For when I guffaw in silence,/ That’s the outcry of statues./ That’s the amusement of stars./ That’s the giggle of ticked stone.”

The poet also has something to say about translation. “On how to translate” presents prose poem injunctions on four elements: “Precision. Form. Texture. Tone.” On the last: “What the meaning feels. Or the shade of feeling. In other words, the sound of the flame when a match is flicked. The scent of gun powder when the pistol fires prose. In the epic battle, it is the groan of the uprooted — the slack of the crippled blanket, of the stripped pillow case, of the battered mattress.”

Here’s another favorite: “The philosopher’s pecker”: “While squatting on the side,/ He got reproached by his wife/ For his pecker was peeking/ From the shorts he was wearing./ He smiled, and sheepishly tucked/ That tiny secret he did treasure./ Yet it tickled him pink to think/ How something so little/ Still happens to spill.”

The earlier collection foreshadows Durado’s thematic and stylistic concerns, as with “When a poem gets a hard on”: “A poem having a hard on is impetuous./ As if possessing a will of its own,/ It doesn’t ask permission in saluting/ The busy thiclet of clouds,/ The voluptuous hills,/ The crack on the cliff’s groin./ At times, it just stiffens for no reason/ And knows no place or time —/ If it has a hard on, it has a hard on,/ Even if chance never opened its legs.”

Yes, he’s an exciting poet all right, who deserves much appreciation and recogniton, for his original works in Cebuano and their exemplary translation into English.