A peep into the life of Malang’s women

Malang’s women first appeared like dots in a field, dwarfed by lemon-yellows, carnation, and squares of rust-orange. They are part of nearly abstract landscapes, not the center of them. Their easily recognizable contours — curves insinuating a mother cradling her child, billowing skirts and butterfly sleeves — provide soft counterpoints to the patchwork architecture. They read to me not as passive elements but as anchors to lived worlds. Peering closer into the frame, I get the feeling of peeping into strange homes and happily discovering that someone I know is living there.

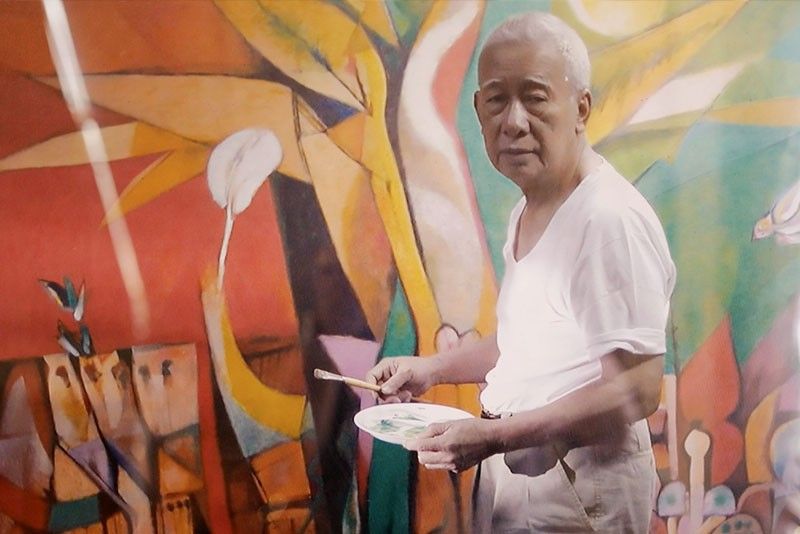

“Dito sila nanggaling,” says Malang’s son Soler Santos, taking me on a mini-tour inside the upper rooms of West Gallery, which is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year. Here in the master’s room, framed finished works abound, but so do tools and objects that trace the process of making: lines of broken oil pastels, open mouths of dried-up paint, scrunched up tubes of oil, paintbrushes, eyeglasses. Although “Malang’s Women” is the theme and title of the show Soler is curating for the Art Fair, it seems that the exhibition is giving tribute to two things: first to his muses, but ultimately to the unending act of drawing that supplied the backbone of his art.

“Fruit Vendor,” ink, by Malang

Twenty-five works on paper, rendered in charcoal, gouache, pastel, pencil, and ink, all convey Malang’s restless and eager hand filling up sketchbooks and loose sheets. His women here no longer inhabit patchwork homes, but he renders their figures with the same amusement and curiosity about geometry. In “Two Women,” the face, split into half-masks, appealingly suggests two faces talking. A long cylindrical shape, colored with primaries, variations of green and shimmering orange, render the body like a totem pole, marking celebrations. These works are playful studies drawn to pass the hours. “Ang maganda raw sa drawing, tuloy-tuloy lang,” says Soler. Rather than revealing a cold eye hounding perfection, Malang’s works on paper have more to do with joy and play.

“Woman,” watercolor

Each one who has ever encountered Malang can recall instances of Malang drawing. Soler remembers a trip to New York where, after a day of visiting museums, his father would return to the hotel to draw. He usually worked on 10 different sketches in a day. In a foreword to a book compiling his drawings, Juan T. Gatbonton writes, “Drawing is Malang’s way of note-taking. It is his way of talking to himself.” Perhaps it had less to do with documentation, but more with setting down thought into something more tangible. He draws, like a diarist catching a reverie.

“Woman,” ink on paper

In reflecting on why his father had the habit of drawing multiple times a day, Soler says, “Sanay siya mag-drawing dahil sa komiks, cartoons. Every day rin ‘yong comic strip niya dati.” Shortly after the war, Malang worked as a layout artist and editorial cartoonist for The Manila Chronicle where his characters Kosme the Cop and Chain Gang Charlie would gain popularity among the public. For roughly 15 years, Malang’s life revolved around printed publications. While routinely waiting for the news of the day, Malang would do his painting in the office. Gatbonton, who was his editor at The Chronicle, recalls the restless artist between deadlines, “looking out on the ruins of Intramuros (and drawing) the barong-barong mushrooming on the gutted Ayuntamiento.”

“Women,” ink on paper

Journalists, critics, and historians, whenever they write about Malang, would always point back to his roots at The Chronicle, and at times, try to downplay the merits of his art on the basis of his training as a cartoonist. A quick scan of the books on Malang housed at the UP Main library would reveal critics trying to pin down his moments of transition in the ’60s, plotting the exact points where the faithful rendering of architecture gave way to blurred planes and textured geometry, where the strong expressions of the cartoon face evolved to a thinning scrawl: slanted lines, a curve, a dot.

“Two Women,” gouache

Done in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, “Malang’s Women” recalls moments after that well-known period of transition. In light of today’s contemporary art landscape, there is no more need to force a distinction between Malang the cartoonist and Malang the artist. Looking at his late works, it appears that he has never completely left figuration, but merely expounded on it, pushing and pulling until the lines have become loose. There are nods to cubism, yes — for Malang was inspired by Picasso — but what these drawings ultimately reveal to me is a hand ever in motion, moving in between styles, in between shapes, and in between times. His entire practice teases the idea that drawing is sculptural — in hammering against material, nothing is ever entirely remade, but only shaped. Marble is still marble, line is line.

“Woman Study,” gouache

Mauro Malang Santos passed on in 2017. His women come to us now as small anchors to his time, testifying to how drawing — the long performance of filling negative space — is also an act of negating the void. I peer in closer into the frames and smile, like a reader discovering Kosme the Cop for the first time.