Non-linear narratives: the ability to hurt, and impress

On the literary extreme would be Julio Cortazar’s ‘Hopscotch,’ which even offered options besides strictly adhering to the numbered pages, with the hopscotching suggested by author himself.

Hardly any novelist still employs linear sequencing any more, so that an essential part of a novelist’s bag of tricks is the narrative configuration she or he settles on. The gambit is to arrange non-linear sequences in the most effective way, withholding revelations until the jigsaw puzzle of characters and chapters that jump back and forth in time eventually or finally makes sense.

On the literary extreme would be Julio Cortazar’s Hopscotch, which even offered options besides strictly adhering to the numbered pages, with the hopscotching suggested by author himself. In cinema, one of the most efficacious renderings of a non-linear narrative, with scenes even repeated from the vantage of different POVs, would be Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction.

With non-linear exposition, a storyteller can choose to start dramatically by employing in medias res, that is, starting in the middle of the story, thence filling up the narrative with flashbacks and flashforwards to keep the reader’s interest.

Even a textual prelude like “Once upon a time, in a galaxy far far away…” didn’t exempt the Stars Wars epic from utilizing in media res, in a larger cyclic way, channeling Greek dramaturgy by first offering Parts 4, 5 and 6 of the middle trilogy, before flashbacking to Parts 1, 2 and 3 that actually start the first set of the story, then jumping forward for the concluding trilogy with Parts 7, 8 and 9.

Even short stories now mostly feature jagged storytelling. The challenge remains: how best to effectively structure a brief narrative or full-fledged, long-form fiction, even memoirs and the rest of creative nonfiction.

I’m happy to report that young writers have taken to this contemporary feature swimmingly indeed, like ducks to water, weaned as they have been on comics lore, let alone video content.

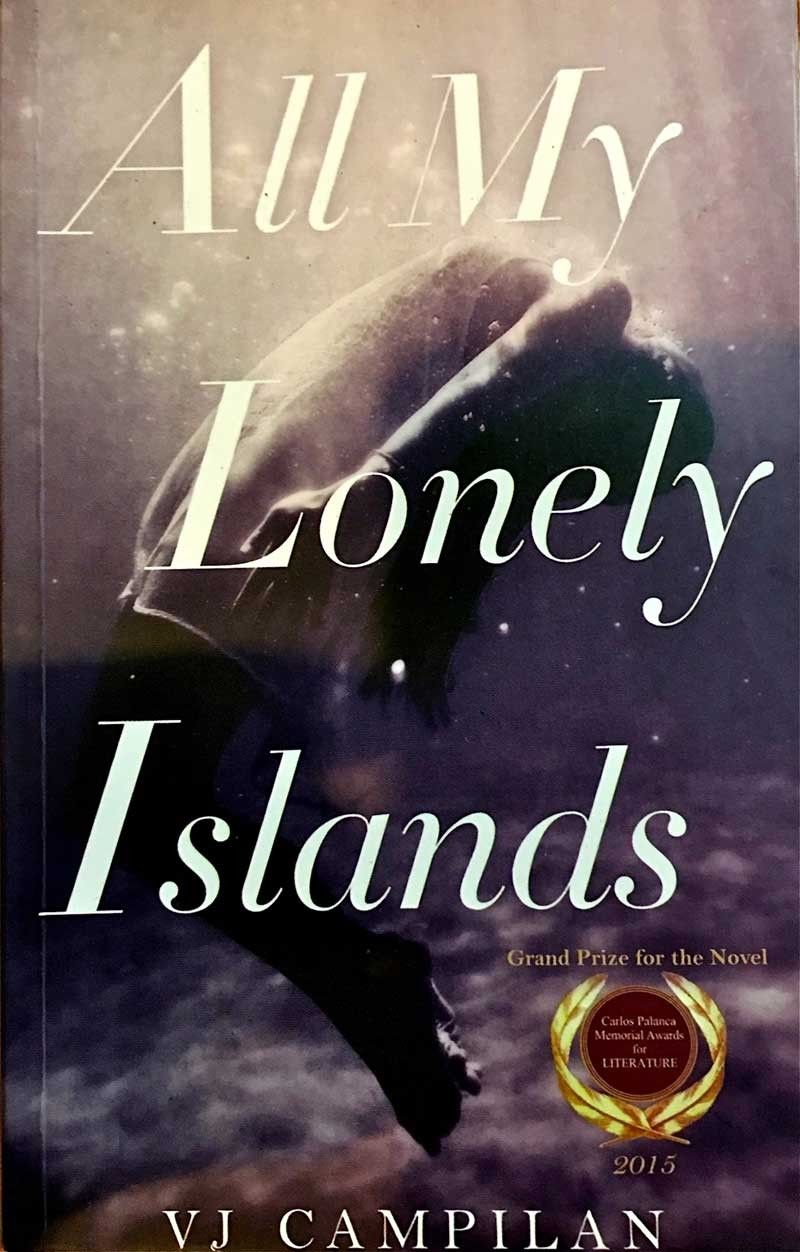

In her debut novel All My Lonely Islands, which won the 2015 Palanca Grand Prize for the Novel in English and was published in 2017 by Anvil Publishing, VJ Kampilan succeeds in turning a coming-of-age story into a taut narrative that strikes all the right notes in suspending cumulative realization — with incremental patch-weave until the final pages.

This deft accomplishment fully complements her skills at clear, precise, detailed and engaging articulation, whether she’s imaging an environment, portraying a character, or musing on the relationship concerns and moral travails of a teen-ager.

Crisanta, whose POV serves up the narrative as staggered episodes and sections, is mystifyingly abandoned by her mother upon childbirth. She is reared by her father Julian, a gentle disciplinarian, and the spinster Aunt Ramona who dispenses pithy folksy wisdom. They’re middle-class Protestants beholden to the Holy Book. The adventurous, streetsmart Crisanta is made to take early piano lessons.

At 14, Crisanta is brought by her dad to Bangladesh where he engages in social work with the Doctors Without Borders. She’s enrolled in the International School in Dhaka where she learns to relate with her high school cohort of various nationalities. Among them, centrally, are fellow Filipino Stevan, who becomes her closest friend, and the American A-lister Ferdinand, school athlete, heartthrob, and manipulative bully.

Stevan’s mother Graciella provides comfort by urging on Crisanta through music lessons, the older woman having fallen just short of becoming a concert pianist.

Throughout the back-and-forth period sequences from Batan Island in Batanes where Crisanta and Ferdinand find themselves on a mission a decade after finishing high school, to the substantial recording of teenage life in Bangladesh, the first-person narrative occasionally addresses a “you” that remains mysterious, until the gaps are finally patched up.

It’s a mature voice that tells the story. Crisanta is intelligent and sensitive, however prone to angst that she mitigates by falling back on Bible studies and religiously writing a journal.

When a foreign classmate attempts to turn her into a cheating accomplice, Crisanta makes a clear-headed moral decision.

“One tries to do the right thing at all costs. I figured a deception cancels a deception, and the status quo would be reinstated. But Gloria approached me with the same proposition for South Asia History, and that was when I decided that sometimes you just had to be cruel to save someone’s soul. I went to Mrs. Gregory and told her Gloria planned to copy my answers for the exam and she was suspended for a week.”

There’s nothing self-righteous with her decisions, however inordinate the degree of emotionalism that often besets her. And Crisanta as the author is as sharp with her prose as her calculations of blood or brethren relations.

“Sometimes they looked like a normal couple, especially during the dinner parties they hosted. They would have the easygoing, intimate aura of a long-established union. And there were no more hushed fights and weeping in the dark. They were a painting done over the years, the colors had sunk in, the lines etched, the blank smiles setting into the canvas. After nearly two decades of expatriate living and a parcel of bastards emerging from behind the curtain, they finally got the hang of marriage.

“It wasn’t until he turned sixteen that Ferdinand found out why his mother endured it all, a few weeks before we had the class trip to the Sundarbans. And by that time, his heart was a flint ready to erupt into a fireball, and anyone could have set it off.”

In what turns out to be a farewell letter from the “you,” Crisanta’s place in a motherless world is best enunciated.

“… Do you want to know the truth about mothers? About parents in general? They’re more afraid of failing their children than they’re afraid of their children failing them. Because when you judge someone, you also judge the people who raised them. That’s how it is when you hold your own child for the first time, you think I can’t mess this up. But we do damage our children in some way. What comes with flesh and blood is the ability to hurt….”

All told, it’s a consummately written debut novel that VJ Kampilan gifts us.