Art that toggles between power and delusion

Long-time partners-in-chime Jose Tence Ruiz and Dengcoy Miel display their works in harmony while expressing disharmonious concepts.

On exhibit until Jan. 5, 2019 at Art Informal in Greenhills East is the two-man show billed as “Toggle: Engage – Disengage” — featuring long-time partners-in-chime Jose Tence Ruiz and DengCoy Miel.

Thirteen pieces by Ruiz and five by Miel are displayed in harmonious complementation, ironically enough while expressing disharmonious concepts and motifs as intriguing arguments against the false premises of the Pinoy quotidian.

Curated by “Bogie” Tence Ruiz, the effervescent (as in boiling up, from challenged sources of everyday acceptance) totality goes beyond synergy, since it ascends as buzzing geysers of either-or and vis-à-vis contrapunto. Ruiz provides fizzing prose as a statement, titled “Decisive Ambivalence.”

“It is eye opening to learn that a word as commonplace as toggle began its useful life in a brutally different context. This item, which describes a switch that in sequence has alternating opposite effects, was preceded by a toggle more predatory: a harpoon, equipped with an iron spearpoint that pivoted where the point met its shaft, so that in withdrawing the harpoon, one dragged it through blubber and drew out a 90 degree turn, transforming the lance into a t-shaped barb which would not be pulled out of its desired victim, in this case the 19th century source of urban energy, the whale. Thankfully, our daily exercise of the toggle is way more benign, the activation or deactivation of any of a set of devices that energize our cities, 21st century urban energy minus the blooody blubber.”

He adds: “What we of the era of uber convenience may be toggling into is an indifferent ambivalence, one which accepts then rejects then re-accepts the excesses which are now prevalent, both on the net and in the general zeitgeist of our brick and mortar world. Just to contemplate oscillating between the virtual and the concrete is another toggle we perform daily.”

Whether the ambivalence is decisive (oxymoronic in a way) or indifferent (short of redundancy), this turns absent when one is confronted with these artists’ creations.

Ruiz’ floor installation “Kulambo” is a large metal cage with uncommon chains extending to the ceiling from its four corners. What is locally familiar as a gauzy net has been transformed into a harsh rendition that suggests another take on reality.

Miel’s first of four paintings is also found in this initial space. “Conquistador” depicts a naked man astride a humongous ball that is a writhing mass of horses, a sword in one hand and a spiked club in the other. The light blue background turns muddy for the foreground with its assortment of pyramidical spikes and more horses about to join the fray.

Also in this first room is Ruiz’ painting, “Monumento ng Bulong,” an assemblage tower composed of details of human hands, some clutching cellphones, enmeshed in a welter of wood and metal frames.

Jose Tence Ruiz’s “Hover”

In the next room is the second Ruiz sculpture, “Grendel,” this time laid out on the floor, stretching angularly like a snake-like monster-machine composed of wood and metal parts with sharp points, festooned with nuts and bolts plus black cloth straps, one end extending as a tangled coil of thick black cables, and the other looking much lile a gothic version of that barbed harpoon cited in the artists’ statement.

Up on a wall by the low stairs is Ruiz’ “Hover,” a painting of a human figure swadded in layers of metalic garments, seemingly in flight, with only its feet and prayerful hands visible, while a seed-pod head and solid gnarled wings also emerge.

An upper room holds five Ruiz paintings, the first titled “The Baroque Burden: Poste” — a richly detailed edition of an electric post burdened by curlicues of leaflike extensions. It presages four similarly vertical paintings that are a series of tree simulations: “The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil…” — “Papaya,” “Palmera,” “Saging” and “Anahaw.” Each one is rococo-rich in fantasized detail, with heavily stylized trunks, leaf fronds, fruits and tendrils that also suggest metal assemblage.

Another room has “Baroque Burden: Baha” (a woman struggling waist-deep in red flood, a solid mass of curlicued mythified belongings on her head); “The Baroque Burden: Sacada” (a field worker with a similar okir-like mass on his head, as stylized sugarcane); and a horizontal canvas titled “Wazaaak!” (a running man in a head-on collision with a jeepney billed as “Pilipinas,” its route detailed on its side: “NAKALIPAS via EDSA86 * NGAYON * HAHARAPIN”).

One room has four of Miel’s artworks, which include a floor installation titled “Lord of Lies” — with our archipelago as white cut-out islands about to be devoured by a large mythological head that’s decidedly Sinic in its features, horns and all, while smaller shark-heads hover about.

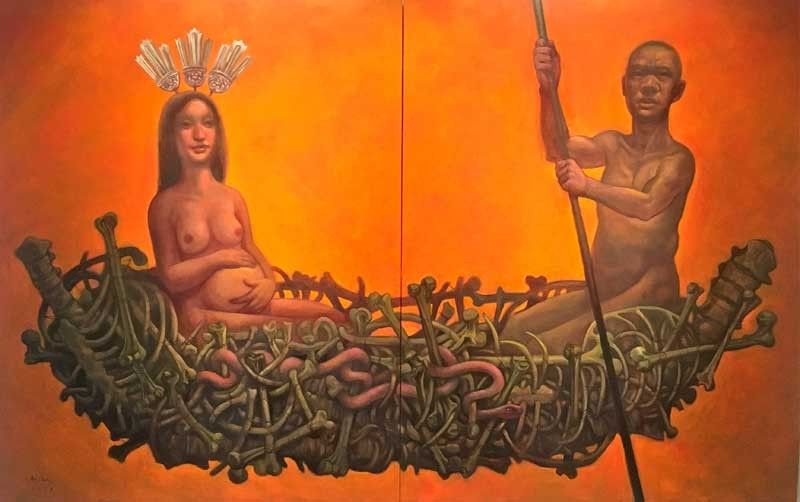

Miel has three more paintings: “La Guerre du Monde” (a naked man with a Morion figure on his chest, his sword having skewered what resembles a whole piece of fried chicken, while overhead is a mass of entangled details of warfare, inclusive of Guernica and Christ references, skull, ribcage, barbed wire and fighter planes); “La Barca de Filipinas” (a naked couple on a boat of skeletal bones and tusks, the woman heavy with child, while the man stoically steers along); and “Optics” (the only realistic painting in the exhibit, showing Dr. Jose Rizal examining a patient’s enlarged eye).

A small room contains Ruiz’ last entry, an assemblage with a painting of a woman on one wall, facing a framed mysterious object, while the entire floor is filled with multi-colored plastic balls, where tablet-like pads are also strewn, bearing the words “Lagog” and “Lagot.” It is titled “Homage to an Homage: For AGG.”

The exhibit fully projects the artists’ statement.

“Miel and Tence Ruiz have editorialized for the last three decades (in reference to their shared experience as editorial cartoonists) and are well aware of the toggling between power and delusion… But they have committed to stilled moments in the sequence…”

The collusion is no illusion, the curtseys to surrealism an occultation of the daily phenomena of civil burdens and challenges, so that “by the time they have sunk their visual spearheads into your consciousness, their insistent toggle at significance shifts 90 degrees into a barb that might not extricate without deep disturbance or pained ecstasy.”