Where have all the great minds gone?

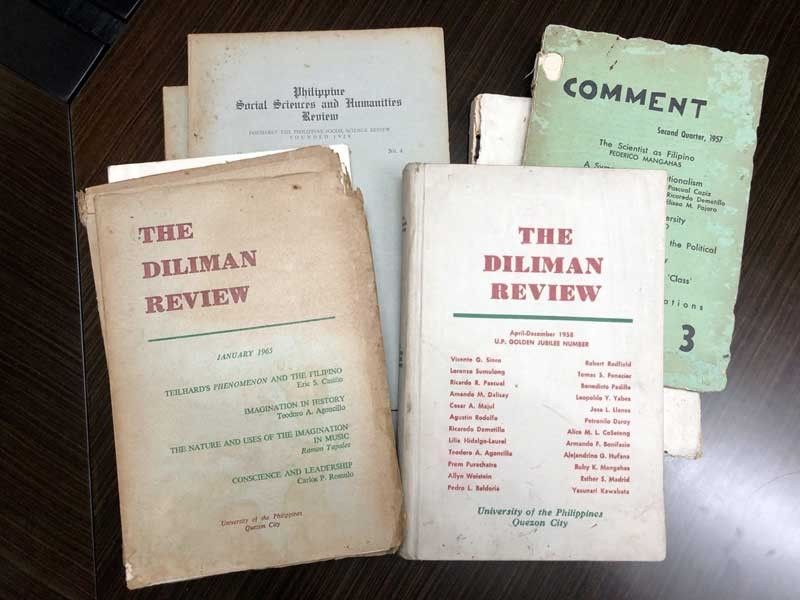

I’m taking stock of my latest acquisition of old books and magazines, delivered to my office by a seller who seems to have hit upon a trove of scholarly materials from the 1950s and 1960s, very likely from the estate of one or two of that period’s leading academics.

They include copies of the Diliman Review, a prominent journal of the University of the Philippines since the early 1950s; the University College Journal, from the early 1960s when UP still had a University College in charge of implementing its General Education Program for the student’s first two years; the Philippine Social Sciences and Humanities Review, established in 1929; and Comment, a liberal quarterly from the late 1950s. There’s a special issue of the Philippine Collegian from 1957 devoted solely to the topic of academic freedom. A unique bonus is a copy of the Golden Jubilee issue of the Diliman Review from 1958 — UP’s 50th anniversary — a handsome hardbound volume I didn’t even know existed.

As I leaf through the yellowing pages of these journals, a troubling thought looms increasingly larger in my head: Where have all the great minds gone? Indeed, where have all the great debates and discourses gone?

In an age of short attention spans, dominated by tweets, where “likes” and “retweets” have taken the place of scientific verification, there seems to be little room for these ponderous journals and the topics they embrace, whose complexities our times would demand to be reduced to 10-word “hugot” lines or 280-character tweets.

A cursory scan of the contents of these journals and their authors reveals the prevailing anxieties and ambitions of half a century ago: “The Chinese Exclusion Policy in the Philippines,” by Tomas S. Fonacier, PSSHR, March 1949); “The Scientist as Filipino,” by Federico Mangahas (Comment, 1957); “The Filipino Struggle for Intellectual Freedom,” by Leopoldo Y. Yabes (Collegian, 1957); “A Republic Within the Republic,” by Salvador P. Lopez (Collegian, 1957); “A Portrait of the Filipino Composer as Artist,” by Ester Samonte-Madrid (DR, 1958); “On Contemplating a Life: The Study of Biography,” by Nieves B. Epistola (UCL, 1961-62); and “Imagination in History,” by Teodoro A. Agoncillo (DR, January 1965).

What’s interesting is that we’re not just talking about ourselves, to ourselves. A man summarily described in the notes as “a Japanese fiction writer,” Yasunari Kawabata — the Nobel Prize winner for Literature in 1968 — contributes a short story, “The Moon in the Water,” to the 1958 DR issue. The foreign scholars Ernest J. Frei and Francis X. Lynch, SJ essay the development of the Philippine national language and the Bikol belief in the asuwang, respectively. The legendary Ricardo R. Pascual dissects Bertrand Russell, Marinella Reyes-Castillo takes on Andre Malraux, and Juan R. Francisco — later to become an Indologist — explains the philosophy of Mo Tzu. And displaying what it takes to be a true intellectual, Agustin Rodolfo, a professor of Zoology, writes about “Rizal as Propagandist” and “The Sectarian University.”

I see that even government bureaucrats then were expected to be literate and to be able to articulate their policies beyond press releases and interviews. The 1958 DR issue includes essays by Amando Dalisay, then Undersecretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources, on “Economic Controls and the Central Bank” and by Sen. Lorenzo Sumulong on “The Need for Economic Statesmanship.”

I wonder how many of these names will still resonate with Filipinos below 40, even within UP itself. I’m guessing that “Agoncillo” might trigger a vague notion of nationalist history, but that will likely be it, which means that we have lost our sense of an intellectual history and of the traditions that colored it — say of the great debates between the University and the State on the issue of academic freedom — and of our sense of quality or even greatness of mind, and what it takes to achieve that standard. Sadly, our academics today are too often trapped in theoretical jargon, in party doctrine, and in self-obsessed mewling to make truly insightful, original, and meaningful contributions to national discourse.

As I contemplate retirement three months hence, these books and journals remind make me proud of UP’s past and hopeful for its future, if it doesn’t forget its basic mission as a producer not just of smart employees but of new and bold ideas.

Where are these minds today, and especially, where are they in government—in the Senate and Congress, let alone the Palace — where they should matter most? In an essay for the University College Journal (First Semester 1963-64) titled “The Filipino Scholar,” the late Prof. Leopoldo Y. Yabes — himself no mean scholar of literature and the humanities — complains that government has been taken over by mediocrities:

“It is quite disheartening to see the spectacle of puny, warped minds having anything to do with administration and direction of intellectual activity on the local and national scenes, of unemancipated minds exercising power over other minds more liberated and definitely superior to them, of parochial intellects charged with the solution of problems beyond their ken and pretensions. Their scholarly prestige seems to be built not on the basis of actual meritorious achievement but by means of press release and other mass communications media.”

I turn my TV on to witness the gaudy train of senatorial hopefuls, many bringing little to the table but their showbiz ratings and their connections to power. I turn the TV off and reach for my books.

* * *

Email me at jose@dalisay.ph and visit my blog at www.penmanila.ph.