That ’70s movement

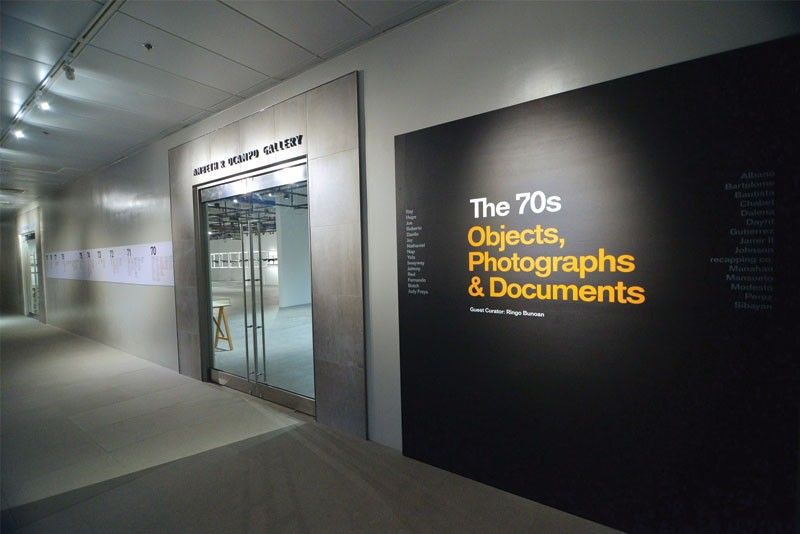

‘The 70s: Objects, Photographs & Documents’ at Ateneo Art Gallery is a nuanced depiction of our own art history during this decade.

Ateneo Art Gallery’s current exhibition on the ’70s depicts the nuances in art history and art education, bringing to light a more complex understanding of conceptualism of the time.

“The 70s: Objects, Photographs & Documents” curated by Ringo Bunoan is an art historical take on conceptualism in 1970s Manila. Featuring works from 15 prolific artists, this exhibition brings to light not only works made at the time, but its historical and political context.

In 1972, late dictator Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law. During this period, many artists created works in response to this declaration. Often depicting dark, emotional, and visceral scenes, social realist painters used their medium to portray issues faced by marginalized groups and communities. However, the ’70s was also a time for the exploration of mediums and meanings, while often criticized for being apolitical or apathetic to class struggle. These two schools of thought are often looked at as separate from each other, made distinguished by their formalist qualities.

Joe Bautista’s “Bubong” installation

The problem with art education is that it often serves to distinguish, to draw boundaries, and to separate one thing from another. In Western art education, we’re often taught to memorize movements and how formalistically different they are from each other, with renaissance art made different from the modernism of the ’60s or the impressionism of Claude Monet’s time.

Of course things are more complicated than just drawing boundaries. Moments in art history often bleed into one another, and there are always works that are stuck in between periods, uncertain of where they would belong. It’s interesting to think about how we are able to classify things, or how we can assume that people make the same type of works at a given time.

“The 70s: Objects, Photographs & Documents” is a nuanced depiction of our own art history during this decade. In this exhibition, Danilo Dalena’s body of work is made more complex, with an installation atypical to what he is commonly known for. His paintings have often depicted the mundane in the underbelly of Manila. However, in this show, we are able to witness his work free from figures and scenes; instead, he exhibits simple objects available to everyone. Entitled “Tulo”, his work is composed of jars, pots, basins, and rusty corrugated steel. In doing so, Dalena makes real, palpable, and memorable the act of using these pots, jars, and basins to collect rainwater from a leaky roof.

Danilo Dalena’s “Tulo” installation

In the same line, Joe Bautista also used corrugated steel in his work, “Bubong.” His work recreates a roof and invites visitors to interact with it by climbing up and walking around. In its first iteration, former first lady Imelda Marcos ordered for it to be taken down because the CCP then would not exhibit works like Bautista’s installation. This work clearly did not align with standard definitions of artistic beauty, and in the same vein, his use of rusty materials acted to reflect typical housing conditions of informal settlers.

Social realism and conceptualism did not happen one after the other, nor do they work parallel to each other. It’s easy to make boundaries and oversimplify different perspectives, but art education needs to be looked at with nuance. Blindly memorizing movements limits people from considering the act of art making as a holistic and interdisciplinary practice, one that embraces experimentation and complexities.

* * *

“The 70s: Objects, Photographs & Documents” is on display at the Ateneo Art Gallery’s new space in Areté until July 2. For information, visit http://ateneoartgallery.org/.

* * *

Arianna Mercado is the recipient of the 2017 Purita Kalaw-Ledesma Award for Art Criticism — which is presented by the Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation Inc. [KLF], Ateneo Art Gallery [AAG], and The Philippine STAR.