‘Lakas ng Loob’: Reintroducing Cesar Legaspi

Editor’s note: Paula Acuin won the 2015 Purita Kalaw-Ledesma Prize for Art Criticism, which is co-presented by the Ateneo Art Awards and The Philippine STAR. Acuin is a graduate student and a teacher. Formerly the exhibitions head of the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design at the De La Salle College of St. Benilde-School of Design and Arts, she currently teaches film, media and humanities at San Beda College Alabang. This is Acuin’s winning piece.

Quarries quiver, hands and feet jut out from uneasy limbs, sky and sea jostle with the whirl of bodies in space. There is much music to be played, a consonance between thickets and flesh, gusts of light and dark.

This exquisite kind of strain plays out when looking at the works of Cesar Legaspi: from the bold, angled forms in softened tones rendered in a range of colors to the artist’s earlier, more somber and muted works — there is an expanse of ideas, both visually and conceptually, that one is able to navigate within Legaspi’s relentless inquiry into “the cubist idiom.”

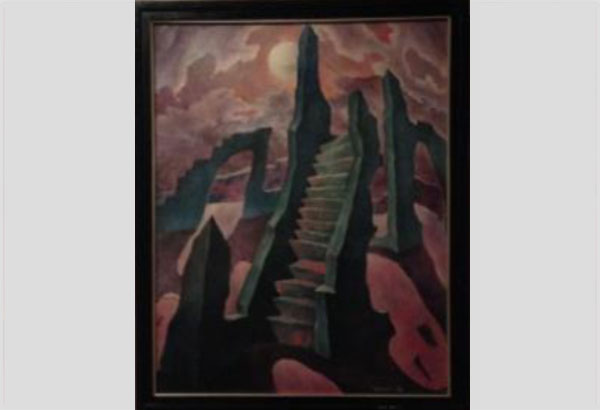

In the artist’s world bodies become part of landscapes, cogwheels and even the atmosphere. His images are always so meticulous in technique and charged with an intensity that is consistent from “Stairway” (1949), an early work born of post-war, pockmarked Manila, to his latter experiments in watercolor as in “Son et Lumiere” (1981).

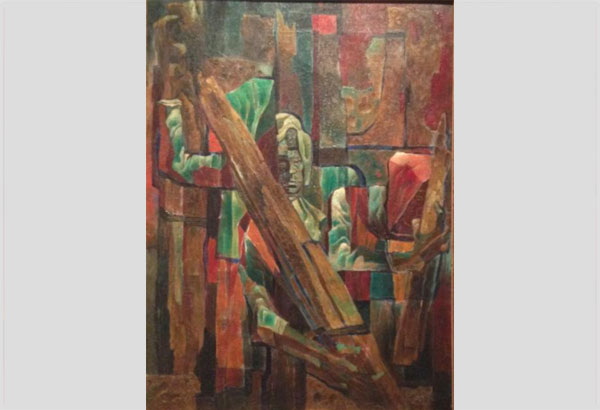

“Wood Gatherers” (1948) by the late Cesar Legaspi, National Artist in Painting

“Cesar Legaspi: The Brave Modern” at the Ayala Museum features a selection of the artist’s work as part of an exhibition series titled “Images of Nation,” the museum’s program for recipients of the National Artist Award for Visual Arts. These solo exhibitions were conceived to “allow the viewers to understand the extraordinary vision and formal excellence embodied in this most important national award.”

More importantly, it positions Legaspi as a “brave modern” having continuously developed his particular adaptation of Cubism — what would later be called “transparent Cubism” — through crises both personal and external.

The Tondo-born artist, who died in 1994, received his art training in Manila, Madrid and Paris in the midst of post-Commonwealth Philippines. He is often mentioned alongside Vicente Manansala and HR Ocampo as the founders of “Neo-realism,” a term the artists introduced in their pursuit of a new style (albeit profoundly influenced by European Cubism), and, concomitantly, as recruits of Victorio Edades in his “Thirteen Moderns,” a loose gathering of artists whom he considered vanguards of modernism during its heady beginnings.

Legaspi was an illustrator and an art director in advertising for over 30 years, which meant that a considerable number of his paintings were done while holding a full-time job in commercial art. The uncertainties of war and its aftermath forced the artist and his family to move within Manila and its immediate cities, the consequences of which could be felt in the multitude of themes expressed in his paintings.

These themes recapitulate themselves in the most fascinating ways. His fastidious experiments in representing the belabored body, for example, can be seen from the tightly riven, almost-monochromatic “Wood Gatherers” (1948), and “Stoneworkers” (1950), to the more freely-chiseled and luminous tones of “Kargador” (1982) and its darker, more “abstract” version, “Struggle” (1972).

“Stairway” (1949)

The Filipino/Tagalog phrase “lakas ng loob,” which may also translate to “bravery,” feels much closer to how Legaspi lived his life as an artist. At 70 years old and diagnosed with cancer, he was building his studio, employing an assistant and exploring new methods and bigger canvases. He would describe himself as a frail and shy boy growing up, but his dynamic and painstakingly made paintings suggest otherwise.

His ingenuity and assiduous commitment to his work can be seen whether he is depicting the heaviness of earth and industry or the languid tempo of a piano piece. Inner tenacity and guts — a decided effort towards sustaining lakas ng loob — these are unquestionable qualities of Legaspi.

But while the exhibition attempts to show this by offering a range of his work (roughly from the late 1940s to early 1980s) and a mix of well-known and seldom-seen pieces, there is a sense of disconnect between the different moods and styles, figures and themes, in the presentation of the works.

In viewing the show there is a difficulty in finding a course through which one may discern the transitions that occurred progressively in the artist’s practice and, subsequently, some context as to why these investigations into Cubism — a largely historicized, “belated event” in the country — should still mean anything to audiences today.

In relation to this is the need for an equally central discussion towards the terms “modernism” and “modern” in relation to what Legaspi has come to represent. As we look back on this critical moment in art history one may ask: how are we to reappraise this once thrillingly foreign and radical idea of the “modern”? This idea and its moment, after all, are suggested by the appellation “the brave modern.”

While it is also often wiser to include more work than biography in a quasi-retrospective such as this, there seems to be little presence of the meaty, supporting material about Legaspi’s life and career in the exhibition. One wonders: where are the photographs, illustrations, magazine ads and texts?

His prolific work in advertising, membership in the “Thirteen Moderns” and “Neo-realists” groups (both of which were all about talk and manifesto-making), and even his leadership of the still-active Saturday Group, could have added texture and much-needed context to the works. Though mentioned in the catalogue and in a sprinkling of wall text, there is a lack of a sense of the period within the exhibition itself.

It is thus bewildering to see next door a very thorough exhibition on Fernando Zobel, complete with a reconstruction of his studio in Spain, and, downstairs, an extensive display of a collector’s early works and studies by Ronald Ventura.

Which brings us back to how this exhibition was conceptualized in the first place: as an homage to the state-administered National Artist Award. Already a hotly contested affair, the award today has reached an impasse so that there are conferments in limbo and petitions for a review.

For an exhibition with a desire to reaffirm the award to an already jaded audience — reintroducing a remarkable artist nonetheless — it is unfortunate that there was a need for more vigor in its discourse and design. The energy of the work and the temperament of its time certainly demand otherwise.