Filipinos at the Field Museum

As Manila got busy with preparations and lockdowns for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit, Beng and I flew out to Chicago for the culmination of a cross-continental initiative of another kind: the Art and Anthropology project hosted by the Field Museum and funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

A few months ago, sometime in August, five Filipino-American artists (Jennifer Buckler, Elisa Racelis Boughner, Cesar Conde, Joel Javier, and Trisha Oralie Martin) came over to Manila to work with their homegrown counterparts on a large mural (technically a free-standing painting) featuring objects from the Field Museum’s vast collection of Philippine anthropological artifacts. That phase was hosted locally by the Erehwon Art Center in Quezon City, on the board of whose foundation Beng (aka June Poticar Dalisay, the painter and art conservator) sits as vice president.

This October, the five Filipino artists (Leonardo Aguinaldo, Florentino Impas Jr., Emmanuel Garibay, Jason Moss and Othoniel Neri) went to Chicago to do the same thing —working collaboratively with the Fil-Ams on a 28’ x 7’ mural at the Field Museum, locating ancient Filipino artifacts in a more contemporary and inevitably globalized context.

Field Museum co-curator Alpha Sadcopen guides us through the Philippine Collection in the underground vaults.

The moving spirit behind this project was the indefatigable Dr. Almira Astudillo Gilles, a Chicago-based Filipino-American cultural scholar and activist who also happens to be a prizewinning writer and presidential awardee for her work as an overseas Filipino. Inspired by the Philippine artifacts at the Field Museum, Almi — the only Filipino research associate at the Field — had secured a grant from the prestigious MacArthur Foundation for the project, which both the foundation and the museum acknowledged to be groundbreaking in many ways.

Better known for its so-called “genius grants” awarded to outstanding individuals, the MacArthur Foundation rarely provides funding for large institutions like the Field Museum, Almi says, but they saw in her proposal an opportunity to spur not just a trans-Pacific collaboration among artists but also a dialogue with the past. And there was no better host in the US for this project than the venerable Field Museum, whose collection of indigenous Philippine archaeological and ethnographic materials — numbering around 10,000 objects, most of them brought over by museum expeditions to the islands at the early part of the 20th century — is one of the world’s most comprehensive.

The mural produced by the artists in Chicago — which will be on display at the Field for six months since its formal unveiling last Nov. 7 — is both a celebration and indictment of our rich and complicated history, invoking all manner of element from the archetypal bulol and the revolutionary KKK (a symbol that predictably sparked some controversy, given its American context) to McDonald’s and Tito, Vic & Joey.

For the artists themselves, the collaboration was a rich, if sometimes unavoidably difficult, learning experience — learning about themselves, about each other, about art-making, about the mutable meanings of “Filipino” over time and space. Prior to the project, some of the Fil-Ams had never been to the Philippines, and some of the Filipinos had never been to America; that alone ensured sufficient provocation in their approach to the task at hand. The collaborative aspect itself was a challenge, given the need to manage and balance each artist’s individuality with some overarching purpose or design. But in the end, as Joel Javier would tell me, despite all the dialectics involved, it was “a once-in-a-lifetime experience” that every participant — chosen by a jury in each country — would have signed up for.

Our sortie into the Field Museum — a place I’ve visited quite a few times over the past two decades, but can never exhaust, like the Smithsonian — was made even more special by a private tour arranged for us by Almi Gilles into the heart of the Philippine collection itself, in the underground vaults of the Field. As a certified museum rat and armchair adventurer, I took it as an invitation to die and go to heaven; the closest I hope to get to Indiana Jones was to wear his hat, which I wore on the appointed day.

We were met at the museum by co-curator Alpha Sadcopen, a young Filipino-American woman with roots in the northern highlands; she held the key to the collection, and led us into a large room where shelf upon shelf of tribal and cultural artifacts — baskets, textiles, weapons, utensils, body decorations, etc. — were preserved, most of them never likely to be put on display outside. “I could feel a shiver down my spine,” Beng would tell me later, and I certainly did myself, walking past the priceless objects, and discerning in each one of them a pair of hands, a face, a story.

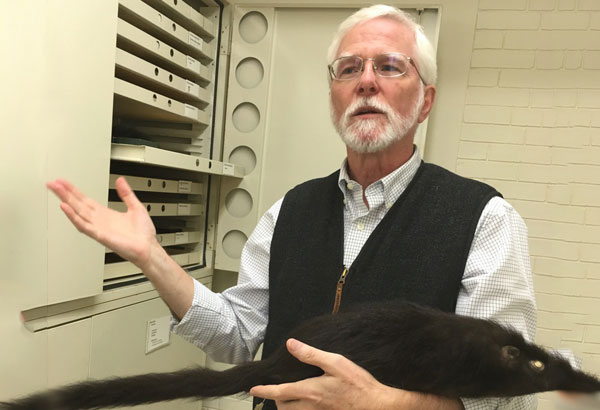

Renowned zoologist Larry Heaney discusses Philippine biodiversity, with a mammal from 1946 in hand.

As if that peek into our material past wasn’t a treat enough, Almi then led us down a few more corridors to meet with another titan of Philippine studies — the renowned zoologist Dr. Lawrence Heaney, curator and head of the museum’s Division of Mammals. Larry began studying the wildlife of the Philippines in 1981, a lifelong passion that has resulted in the discovery of dozens of previously unknown mammalian species, in many landmark publications, and in the establishment, with Larry’s Filipino colleagues, of the Wildlife Conservation Society of the Philippines.

We often think of world-class scientists as surly, self-absorbed individuals who can’t relate to anything beyond what they see in their microscopes and telescopes, but Larry defies that stereotype. You couldn’t have met a nicer man, and one who chose not only to sound the usual alarm about our threatened environment, but also to emphasize the positive and the possible. “Hectare for hectare, the Philippines is the world’s richest place for endemism,” he told us, cradling what seemed to be a huge rat saved from a 1946 expedition to Luzon, “and there certainly are serious threats to Philippine wildlife, but we’ve also noticed some bright spots. For example, the growth of overseas jobs for many Filipinos — despite its social costs — has also eased the pressures on the environment and on wildlife in many rural communities.” Dr. Heaney is coming over to Manila next year to launch another book, and I’ll be sure to be there.

And what’s next for Almi Gilles? She’s looking skyward, into the connections between Philippine anthropology and astronomy. Her colleagues at the museum seem thrilled by the idea, and so are we.

* * *

For more pictures of the Philippine collection at the Field Museum, see here: https://www.flickr.com/photos/penmanila/albums/72157660699359089.

* * *

Email me at penmanila@yahoo.com and check out my blog at www.penmanila.ph.