Here’s a Japanese anthology named after a Chuck Berry boogie

There’s hardly anything to dislike about Japan. I was one of those who, after booking the cheapest roundtrip tickets to Nagoya last year, fell hopelessly in love with the country. The food was superb, the people were polite and friendly (especially our own kababayans there), and public transportation was such a joy to take. My two siblings and I were so happy with our first visit that we made a pact amongst ourselves to go to a new prefecture each year. We’ve been at it for two years and there seems to be no end yet in sight — there are 47 prefectures all in all.

Unlike anywhere else we had ever visited, Japan had an order that loved chaos but was hardly chaotic; an outlook that saw cosmopolitan evolution as only natural. I saw it as a land living on and thriving with contradiction: East meeting West, the odd combinations and symmetries of the old and new, of heritage and forgetting, of prayer and noise, of hard work and meaningless fun. And for those of us who went there unarmed with a single Nihongo phrase, the strangest thing was that everywhere we went, somehow the words the places spoke of were loud and clear.

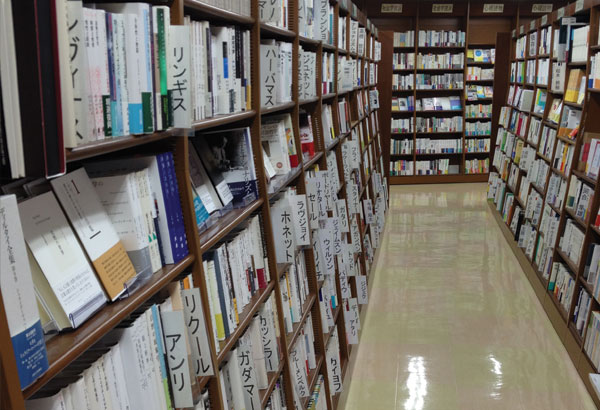

All said, the irony was that it was in their bookstores where we felt like the most unwanted aliens. Some branches of Kinokuniya — their equivalent of National Book Store, only much neater and loaded — had four or five floors lined with shelves which reached the ceiling. However, one had to do an Easter egg hunt for books with letters instead of calligraphy. And while it made sense in our heads for Kinokuniya to have an all-English section, it didn’t seem to fit with the elegant simplicity of Japanese design. But I guess the frustration stemmed from the fact that we felt like we understood Japan well, but we couldn’t find the words to describe or define it. (Talk about contradiction!) The bookstores made us feel claustrophobic; we couldn’t find a book which would give us a pat on the back and say that, “For tourists in Japan, you guys are doing fine.”

No English here: a typical bookshelf at a bookstore in Nagoya. Photo by DLS Pineda

Fast forward to Ayala Museum last Wednesday afternoon when I attended a short talk by Roland Kelts and Satoshi Kitamura, a writer and an illustrator respectively, who both hailed from the Land of the Rising Sun. They were brought over by the Japan Foundation to promote an annual anthology which, true to Japanese fashion, is unassumingly titled Monkey Business: New Writing from Japan. It is a literary publication by Public Space Literary Projects Inc. based in New York and supported by the Nippon Foundation.

Roland Kelts, who was born to an American father and a Japanese mother, started his chat with a sort of disclaimer. “I should mention that this book is a hybrid publication, and certainly like this city — Manila. I was in the taxi last night when I heard on the radio, the mix of Tagalog, English and Spanish. It was quite beautiful, like a symphony of languages. Every place we go to now is a hybrid.”

Monkey Business was founded in 2008 by Motoyuki Shibata. He was motivated by the desire to dispel notions of literature being “too serious,” and novels discussing only “profound” themes like self-discovery and meaning. (And so he borrowed a playful name from a Chuck Berry dancehall boogie.) At that time, it was published only in their native tongue thrice a year.

On 2010, renowned scholar Ted Goosen volunteered to create an English translation of Monkey Business, giving birth to the yearly release of an English version. Today, Roland Kelts, as one of its contributing editors, sees the book not just as a literary anthology but a cultural publication that combines Japanese fiction, essays, short stories, photography, graphic storytelling, and poems.

Kelts believes that there are three tenets that they held dear in the making Monkey Business’ fifth and most recent issue: the discovery of great writing and art; the creation of excellent translation; and the widening of their cultural network. He said, “We only publish what we love. We don’t publish because the person is famous or because they demand that they be published. And we don’t pretend that this is all of Japanese contemporary writing. But we publish them only because these are the works we love.

“Because when you include only what you love, there is a huge chance that someone else will love them, too,” he explained. It was a poetics that would send literature professors scrambling and John D’Agata fans squealing. But at the same time, his plain words made perfect sense.

“Translators have to be excellent writers themselves,” Kelts continued, “Translating is a romance, it’s not just a job —they have to love what they’re translating.” He went on to expound on the importance of creating a wide network of writers from different countries, and the efforts they exert to introduce and meet writers from far away. Somehow, he made it clear that beyond the desk, a writer’s job is to introduce one’s material to some place where it is otherwise foreign. And from there, the writer’s work should create stronger ties and understanding.

Imagining myself back in a Kinokuniya in Japan, I realize how different the experience might have been if only I knew how to read and write in Nihongo. While there is an advantage in being able to write in English without the need for a translator, I wondered, what layer — what contradiction — would translation add to a piece of writing? For if travel writing is done by a writer who’s out traveling, then translation is the words themselves in travel.

* * *

All five issues of Monkey Business are available for order on Amazon.com. You can also browse copies at the Japan Foundation at the Pacific Star Building in Sen. Gil Puyat Ave. Visit their website at monkeybusinessmag.tumblr.com.