Ways of looking at the guardians of the earth

October being Indigenous People’s Month, the issue of the IP’s survival against development schemes, and how best to defend their culture and ancestral domain, is in focus again. This has been a major theme in many of the works of contemporary Filipino visual artists such as Federico Boyd Dominguez, Bert Monterona, and Leonardo Aguinaldo.

Recent events have raised urgent concern about the worsening plight of Philippine indigenous people, especially those living in Mindanao. The specter of ethnocide now haunts several places on that erstwhile “land of promise” — particularly Davao, Surigao del Sur, Agusan and Bukidnon — where the Lumad have lived since time immemorial as animist communities long before the coming of Islam and Christianity.

Well-documented reports by institutions such as Karapatan, Katribu, the Church and other religious groups, and even radio station DZRH have focused not only on the massacres and forced evacuations inflicted on the Lumad but also on the perceived root cause of the conflict: attempts by big local capitalists and multinational companies, with government approval, to exploit the huge mineral deposits in Mindanao for the sake of super-profits.

At various times, the IPs of the world have been idealized or romanticized as the “noble savage” who are better left “uncontacted” and “unpolluted” by modernity. With more compelling evidence do today’s advocates and defenders of the IP and their way of life describe them as stewards and guardians of nature and the earth, from whom modern(ized) humanity can learn so many lessons about self-sufficiency, caring for the environment, as well as social harmony. But this indigenous universe is under threat of dislocation and disintegration.

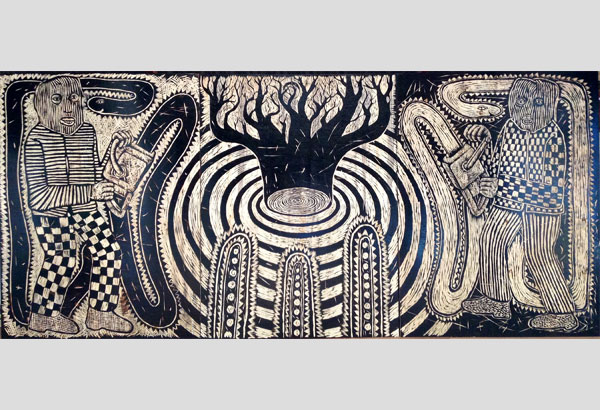

“We Know What You Did Last Night” triptych by Leonardo Aguinaldo

In the works of Federico Boyd Dominguez, the IP are depicted as deeply rooted in their ancient cultures and the natural environment which nurtures them, yet they are constantly under threat from “development aggression.” In the painting “Lumad,” the indigenous cycle of life determined by agricultural seasons, ethno-cosmology, animist presences and celebratory rituals, is hemmed in and threatened by invasive development represented by bulldozers and other earthmoving machines, sugar centrals and other plantation facilities, crop dusters spraying toxins, chainsaws tearing at ancient forest stands, and the ubiquitous military presence which leads to forced eviction and evacuation.

Commissioned by Amnesty International, another signature work by Dominguez entitled “Land Grab” takes this scenario to the global level, the dominant image on the lower right showing marginalized IP of various nationalities retreating further away from the ancestral domain taken over and transformed by commerce, industry, capitalist agriculture, real estate empire-building, and urbanization — by now a familiar scene in pockets of the Third World where IPs live precariously, their cultures, languages, and physical survival in danger of extinction.

Vancouver resident Bert Monterona has consistently depicted the Lumad of Mindanao as a culturally diverse and dynamic indigenous community entirely dependent on the land they have nurtured and taken care of for a long time, wealthy beyond measure in terms of material culture, natural resources, oral tradition and ethnographic art. There is virtually no boundary between the natural and spirit worlds suffusing Lumad cultural practice and worldview — for as long as this indigenous world was safe from interference.

In recent months, there has been a series of violent acts committed against the Lumad in Monterona’s Mindanao. Almost immediately, the artist made known his protest via Facebook, superimposing on a photo of himself and his artworks the growing protest —visibly so in social media — with the message “Stop the Killing of the Indigenous People in Mindanao.”

Many of his works, some of which are mural-sized, celebrate Lumad culture and mythology in colorful visualizations of rituals and beliefs. While the motif is ethnic, the portrayal is not always simply descriptive, but contains the elements of a visionary IP world that reenacts the legendary golden age in some distant future.

Visual artist Leonardo Aguinaldo, a major force in the Baguio art community, has been performing a similar advocacy for the Indigenous People of the Cordillera. His works have included hand-colored as well as black-and-white carved rubbercuts and woodcuts. These have been shown in a trilogy of shows called “Inima” (1, 2 and 3), an Ilocano and Cordilleran word which means “hand-made,” the third edition of large-scale works having been shown recently at the Galleria Duemila.

One of Aguinaldo’s biggest works is a linocut triptych suggestively titled “We Know What You Did Last Night,” a pointed reference to corporate tree-killers who work furtively in the night, cutting down old-stand trees in order to make way for concrete buildings to house commercial stalls and parking spaces, and those who reside in Baguio would be knowledgeable about the allusion. As in the works of Dominguez, the chainsaw appears in Aguinaldo’s images as an instrument of violence that symbolizes not only the death of forests but also the fate of ancestral lands long nurtured by their guardians, the indigenous people of this archipelago.