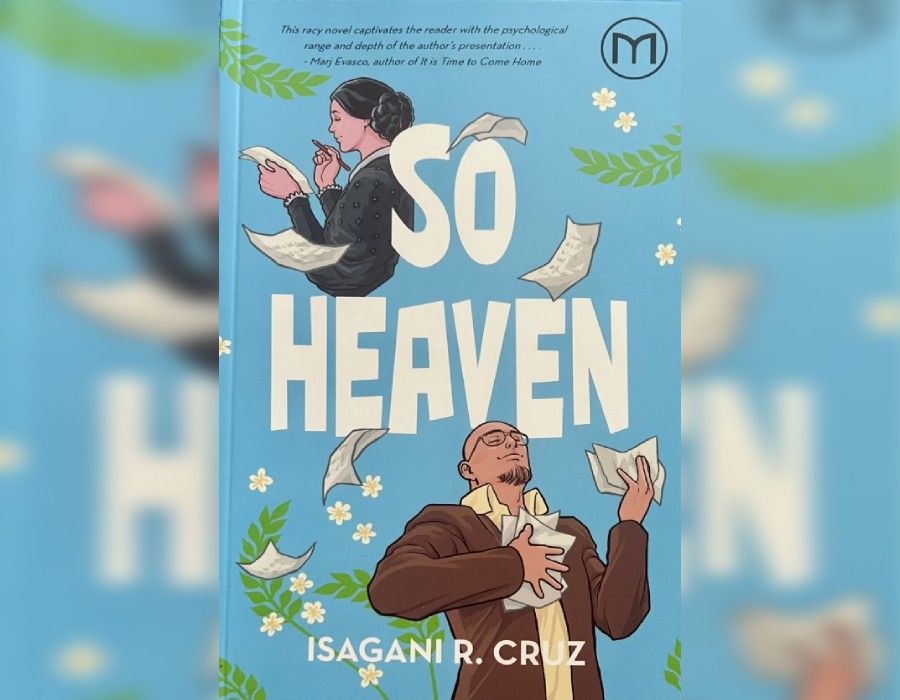

A delightful novel

An exceptionally pleasant surprise is former Philippine Star columnist Isagani R. Cruz’s first novel, So Heaven, published by Milflores Publishing and recently launched at DLSU Taft. The playwright-critic-scholar-professor who has been behind some 70 titles he’s authored or edited, besides organizing such consequential literary organizations as the former Manila Critics Circle that spearheaded the National Book Awards, merits full appreciation since his latest output was accomplished while recovering from a debilitating stroke some years back.

Delightfully woven as speculative fiction, the futuristic narrative revolves around a Musk-like character, Danny Livingstone, a self-made Filipino billionaire owing to his inspired inventions. His raunchy side as a widower is kept at bay with his passion for book publishing, reclusive philanthropy, and game-changing leaps of imagination.

Cruz writes so cleanly and lucidly, eschewing literary flourishes in favor of understandable curtseys to renowned writers spanning several centuries. Early exposition makes effective use of the anaphora, where the syntax features repeated phrases that gain a child-like manner of story-telling. It is also useful in threading through circuitous philosophical turns and the tweaked contours of religion.

But much of the writing simply depends on the introduction of the parade of characters, besides Danny’s internal contretemps.

“He particularly despised all the pioneers and innovators of the past, whose pioneering inventions he had rendered obsolete with his invention of the ear computer. Using cotton buds on his ear was not just sheer pleasure; it was also a daily reminder that much of his wealth had come from exploiting the potential of the human ear as a window to the brain.”

After all, his practicality had him keeping the patent for the software and applications others developed. Another brainchild is the Bookamin, not a gadget but which “also sold in the billions, because reading has become popular again after he had poured millions into promotions and advertising” He has also become “the CEO of the biggest publishing house on earth.”

An eccentric lifestyle has him maintaining the penthouse he had designed “on the 250th floor of his office building (the Livingstone Creations building) in Payatas in Metro Manila” — which momentarily dwarfed the “829.8-meter tall Burj Khalifa and the kilometer-high twin towers in China.”

Another invention, of “the now commonplace carbon and methane recycling windmills,” had reversed climate change and actually saved the world, so that he could transform Payatas into an elitist enclave, with his building becoming “the envy of developers from Dubai to Macau.”

A widower who had also lost his mother and other relations, Danny is content to love his bathrooms, while often resisting the urge to jump off his balcony. Oh, he also adores Emily Dickinson and her poetry, making annual pilgrimages to her home-turned-museum in Amherst.

“If there were indeed an afterworld, he mused, then he might possibly meet Emily Dickinson there. He wondered if people had bodies in the afterlife.”

After this breezy exposition, the author shifts from on omniscient POV to a first-person account, allowing the interiors of a complex personality to suit the jaunty narrative about a horny cad on a metronome from nihilism to existentialism.

“Since I have no love of inanimate objects, like art or appliances, I spend my money on the animate, particularly animated women who make me their mate on my business trips.”

It is the poet Emily, gone for over a century, who first speaks of herself as being in heaven. This follows a chapter when she actually materializes in the present, visiting Danny to ask him to publish her poems the way she handwrote them — with all the dashes, capital letters, and strange spaces between letters and words, before these were all mangled by previous editors and publishers.

Inserted is a parody of a chapter with Shakespeare and his fellow pinters in an Oxford tavern, arguing about virginity.

The time shifts allow these characters to commune in heaven where they have all been. Besides Emily Dickinson and William Shakespeare who both believe that the Lord is female, the company has cameo roles for Albert Einstein and Jose Rizal, a.k.a. Joe, even a mention of Jose Garcia Villa — as they all wait to welcome Danny who may or may not have perished in an accident in his robotic car while the earth-revisiting Emily was his shotgun passenger.

Heaven seems to be an abstraction of a way station, with its residents still managing to transport themselves to various time spheres. And the way they relate to Lord and all others are also mostly in variance.

“… Lord appears to Danny as his father. Lord really knows how to make human beings feel at ease.

“”I’m not your father, Danny,’ Lord says. ‘I brought you here.’”

A fly that appears in a Dickinson poem is recalled by Joe, parallel to the fly that buzzed his nose at the moment of his execution, thus being the real reason why his body twisted towards the east upon the bullets’ impact. But Joe was already in heaven looking down at the scene.

The brief Interchapter 1 (in tribute to Ernest Hemingway) highlights a detail: “Since we have dreams that contradict the dreams of others, our heaven will be very different from the heaven of others.”

An interchapter 2 dwells on “The Sexness of Sex” … “In the spirit of Herman Melville’s 1851 Moby Dick.”

An excerpt: “Like all things human and humanly possible, sex is totally democratic, anarchic, and conventional. While it may be easier for a logician to think of only three possible options according to the tried and tested principle of non-contradiction (man on top, woman on top, neither on top), lesbians, gays, bisexuals, machos, homophobes, heterophobes, omniphobes, and every manner conceivable of sexual preference, identity, orientation, and so on have deconstructed logic and evolved hundreds, nay, thousands, of positions imaginable and unimaginable. In a real sense, sex exemplifies the immovable object that can be moved by the irresistible force.”

Lord sends Danny back to the living to save Annie from suicidal tendencies, as she’s “predestined to find the cure for metastatic pancreatic cancer.” Many other characters are introduced, including Annie’s lover Christine. There’s the lovely Faith whom the ER expert Annie also desires, and her father George Brown, a famous American billionaire who makes love with Christine despite his ED. And gets to marry her.

It’s a virtual rigodon around suites and hospital clinics turned love nests, involving lesbians and bisexuals. Danny realizes that only Annie can see and hear him, while others just walk through his body. During this temporary respite from heaven, Danny is joined by Joe Rizal and Bill Shakespeare. They enjoy conversations (sometimes about their books and plays) when they’re not busy advising Danny to get used to the differences between living and being in heaven. All this while the women engage in frequent sex among one another and an unnamed doctor, plus the lecherous George.

Time travel loops bring in a cast of worthies for mere mentions, such as Wallace Stevens, Benjamin Franklin, Edgar Allan Poe, Jorge Luis Borges, Noah, Osama Bin Laden, Hitler, George W. Bush, Queen Elizabeth I, Alexander the Great, Pope Pius XII, St. Peter, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle (mostly cited in Bill’s/Shakespeare’s) monologue.

It’s an enjoyable read, not just for the spicy passages. Author Cruz has evidently worked in all his gained expertise on hospital practices, history, and literature, and enhanced his imagination with excellent humor. Why, Danny even gets more and more serious with Emily Dickinson, in heaven and not so heaven.