Making Japanese desserts is an art

I wanted to learn how to make Wagashi (Japanese confections like mochi) and Dorayaki (red-bean pancakes) before coming to Japan since, as a rule, I make sure that before I visit any country, I know the culture and the food offered at my destination.

Food has always been a great indicator of the way of life and ingredients that are locally available to that country. I was glad I was headed to a country where both history and tradition were well rooted into their culinary creations.

A good family friend whom I have known for more than 30 years, Siti Okawa, was more than happy to help me prepare for my trip to Japan. Siti made sure that I was well informed about the places I wanted to visit, as well as the activities I wanted to do while I was in Japan.

The first challenge of the trip was to look for a cooking school that could teach me how to make sweets in the traditional Japanese way, and the second challenge was, if we were fortunate enough to find a traditional culinary school willing to teach a tourist, to learn effectively, since the method of instruction in Japan is still predominantly Nihongo. This was the time I was indeed very grateful that Siti was with me during the duration of my stay. She was my interpreter, guide and overall key to my enjoyment of visiting Japan.

Teachers Junko Ando and Yuka Kanuara flank students Heny and Siti

It was Siti who arranged my itinerary, aside from scheduling and arranging visits to different places. Siti always studies with me because she is my translator. She also helped us communicate and immerse in Japanese culture like natives.

We were fortunate enough to find the Wisteria Dorada Instituto Cultural de Wagashi. I was curious as to why a Japanese Wagashi school had a Spanish name. I learned that the school is owned and operated by Junko Ando, who has many Spanish friends. She is very active in promoting cultural exchange between Spain and Japan, thus the name.

Aside from being a Wagashi teacher, Junko is also a good flamenco dancer. Her husband, Yasu, is a good friend of Siti’s and my husband Benny because they were part of the Ship for Southeast Asian Youth Program Batch’79 and kept in touch with each other ever since. When Yasu learned from Siti that I wanted to learn how to make authentic Japanese sweets, he mentioned to Siti that his wife Junko is licensed to teach Japanese sweets, the classes are conducted in the kitchen of his mother, and that she can speak English.

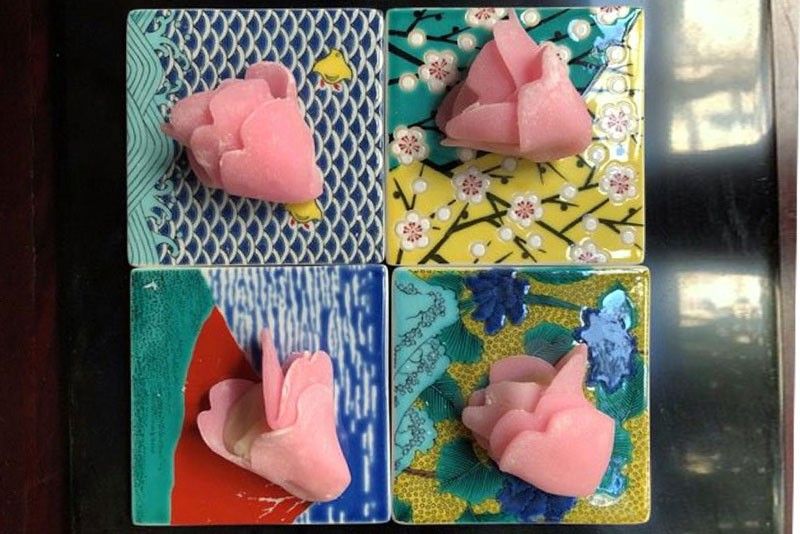

Wagashi are traditional Japanese sweets served with green tea. They are usually made with red bean paste and fruits. Wagashi come in a range of colors, shapes, textures and ingredients. Some are only available during certain seasons or in certain regions of Japan. It was Sakura season when I took the class, so we made a pink-tinted dough representing the color of cherry blossoms.

Learning how to make these delicate sweets starts with the dough. The dough is made with rice powder, glutinous rice powder, flour, sugar and water. It is steamed, then kneaded. Food color is then added by kneading. Wagashi is assembled by rolling, shaping, and then filling them with a pureed sweet paste.

Antique wooden molds used to shape the Wagashi, like the Higashi

The more I learned about the intricate details of making Wagashi, the more I appreciated the fact that the local delicacies of Japan are produced with a deep-seated appreciation of their culture. Each sweet is meticulously prepared with keen observation as to method and consistency.

Color plays a crucial role in the production of Wagashi as the colors of the sweets differ according to the season. We were taught that colors would range from light pastels that would highlight spring colors, all the way to dark pink for autumn. The Japanese believe in the artistic aspect of the seasons and the colors follow the four seasons.

I discovered that different places have different-flavored Wagashi. They take it home after business or personal trips. It is a great gift for festivals and can also be a daily treat for guests as a sign of true hospitality. Some Japanese hosts offer Wagashi right away to give them a unique welcome.

When we arrived at the cooking school, Yasu, Junko Ando and Ando’s co-teacher, Yuka Kanaura, welcomed us with an array of Japanese sweets, together with the traditional tea ceremony. After the tea ceremony, Junko gave us a brief history of Japanese desserts.

I wanted to learn some other Japanese sweets beyond Wagashi. I told Siti I wanted to learn how to make Dorayaki, one of my favorite Japanese sweet snacks that made with two small pancakes filled with a sweet red-bean paste. It seemed so easy to make as I watched Junko make the Dorayaki. The shape of the two pancakes must be perfectly round, like Oriental gongs, when assembled together.

Siti told me that it might be too amateur for me to learn Dorayaki because it is just a pancake with filling. But I told her I had to have the authentic Japanese experience to learn the culture and how it is done in a Japanese home. I am right; making Dorayaki needs precision, the right balance of recipe and steady hands. The pouring of the batter must be close to the nonstick griddle to avoid droplets of batter scattered all over the pan. Cooking time is critical because the color of the pancakes must be burnished gold with a perfect round shape.

Matcha tea powder and tools: Chasen (bamboo whisk), chashaku (scoop for the green tea powder) and chawan (bowl)

There are other Japanese sweets made of flour, and hard sweets made using wooden molds. Junko showed us her collections of wooden molds made from cherry wood that were hand-carved by an artisan Japanese woodcarver. She said she had to wait two years to get a mold done because it is a dying trade thanks to modern silicone molds.

During the tea ceremony it’s also fascinating to see how the tea foams up because of the sequence and the tools used, like the bamboo tea whisk. When you are done you need to slurp the tea to signify that you are done and have appreciated the effort of the person serving the tea.

My takeaway from learning the culture behind Wagashi is that the artistry of combining beauty with taste is part of a tradition of shared wisdom passed on from one generation to the next — a lesson we can learn from. Imparting traditional ways of how to make our local delicacies is crucial to our identity as a people and as a country.

Like Japan, may we never neglect cultural preservation for the sake of modern convenience.