Hidden bubbles

Moving and caring for contemporary art has always been a sensitive and tricky affair whether within or outside the context of institutions (although, as has already been argued elsewhere, is there really an outside?). It is a complex mush of people, energy and phone calls. Moving and caring here involves not just the intricate art of art handling which may include, among others, packing, installing and mounting art, but also the bigger, more variegated field of collections management where the definition of the job gets even broader: Art needs to be stuffed, wrapped, encased, framed, cushioned and sealed for storage and/or transport.

It also includes the gluing, measuring, boxing, crating, drilling, and labeling of goods — art goods, rolling on and off vans and trucks (sometimes, if you’re lucky, in spacious, superluxe, private SUVs), careful and discreet operations carried out through copious amounts of paperwork bearing negotiations, conditions and signatures, “noted” and “endorsed”-bys in duplicate and triplicate. Environments are assessed and surveyed. It is excessive use of industrial-grade tape and bubble wrap: the art market “bubble(s)” that never burst.

It’s fascinating stuff. Artists have made thoughtful investigations on “the politics of the field of art as place of work” in what has now been called “institutional critique.” Five years ago, artists in the US established #occupymuseums. Three years later, a scientific conference on art handling was organized in Switzerland. The first Ural Industrial Biennal of Contemporary Art in Russia took on the task of examining “problems of material and symbolic production, (and) industrial and artistic labor,” referencing Stalin’s “shock workers” — an invented, glorified status conferred to factory workers to increase production.

The effectiveness of these efforts, however, remain to be seen. In this side of the world, art labor or, perhaps, laboring for art remains a largely concealed enterprise. It is well-known that objects and ideas assume a state of detachment (one may even say, innocence) once positioned and lighted in a decent room with labels and curatorial text. The opacity and certainty of this phenomena in relation to the people who are responsible for its fruition remains an obscure and exotic concept to most audiences of art. The idea of workers and work behind an artwork (and this may sometimes include the artist-producer herself) melts in the soft hush of the air-conditioned air inside the gallery space.

The hidden work of caring for art executed by so many gallery bantays, handlers, carpenters, drivers, assistants, movers, manongs and manangs, security guards, yayas and volunteers reminds us also of other kinds of care that circulate in and sustain our economy. (This was suggested by Orlando Reade in his essay “What Does the Art Handler Know?”) While these stealth art workers do not always crave for attention, they do echo the nameless and faceless strains of globalized care provided by Filipino caregivers, nurses, nannies and technicians all over the world: unseen, poorly compensated care that drives and buoys the visible workforce.

But then again, what field does not engage and thrive in and among this kind of dirt? This unevenness? As Reuel Aguila reminds us in his short story “May Katulong sa Aking Sopas”:

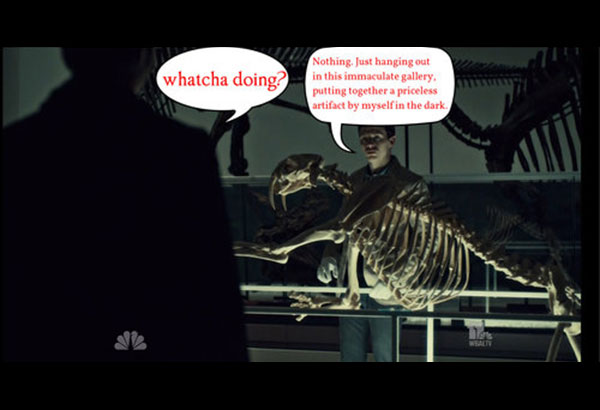

Image from whenyouworkatamuseum.com

Walang dakilang lipunan ang naitayo nang walang nauutusan… Ang katulong… ang nagbibigay sa akin ng panahon upang maging libre ako at pakinabangan ng lipunan. Sila, sa kabuuan, kung gayon, ang lihim na mayoryang nagsisilbing gulugod ng lipunan. (No great nation was built without slaves… The maid… gives me time so I can be free for society to use. They are thus, the secret majority that serve as the backbone of society.)

Nothing is natural about this current state of things. Aguila in his story also very keenly points out that it is mostly women who are expected to care and give care to both their families and employers. This, too, is not natural, hardly unmediated.

One wonders when this idea of the country as “a nation of caregivers” perpetually doomed to deal with bureaucratic policies and unscrupulous manpower agencies just to leave their families (in order to care for other families) will slacken and end. Visibility — the kind that spurs dialogue and documentation — is critical for workers who are often forced to maneuver themselves within these dangerous conditions because not only are they hidden: they are also actively buried and forgotten.

Art workers may not always find themselves in such extreme situations but their non-existence in the discourse of the politics of art is, when one thinks about it, strange, if not troubling. Their presence (or absence) is indicative of a world of contemporary art that, for all its entertaining and variant roles, is not immune to the vicissitudes and entanglements of work, care and labor.