The Odyssey of F. Sionil Jose

Maverick National Artist F. Sionil Jose has just passed away at the age of 97. UP Professor Jose Wendell Capili telescopes for us the odyssey of Manong Frankie in “Migrations and Mediations: The Emergence of South East Asian Diaspora Writers in Australia,” UP Press 2016.

While T. Inglis Moore was busy waging battles in Australian literary landscapes, Manong Frankie was visiting Robert Frost in his cottage in Ripton, Vermont, in 1955. He had received a Smith-Mundt Leader grant from the US State Dept. to meet Frost, the critic Malcolm Cowley and John Crowe Ransom, the poet and editor of the influential Kenyon Review journal, published by Kenyon College in Ohio.

Two grants from the Asia Foundation – one to visit the Middle East and South East Asia for one month (1955) and a second (1960) to revisit the US and South East Asia and to tour Latin America – enabled him to make valuable contacts with other writers. He also became the editor of Asia Magazine, a Sunday supplement distributed in Asia, from 1960-62. True to form, he suggested that the magazine should have a literary section to highlight the authors of South East Asia, Australia and New Zealand.

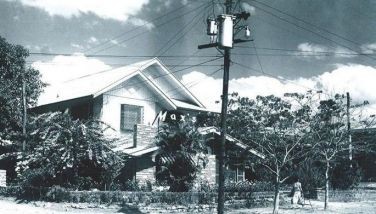

He then moved on as the Information Officer at the Colombo Plan Bureau in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) from 1962-64. Using his savings from this post, he and his wife Tessie opened the now-legendary Solidaridad Bookshop and publishing house in 1965 in the latter’s old family house on Padre Faura Street, Ermita, Manila.

The Joses rented this house until April 1976, when they took out a mortgage on their own home to buy the bookstore’s building from Manang Tessie’s family. From the get-go, Manong Frankie intended the bookshop as a showcase for Philippine and South East Asian writing. It may well be, as Manong Frankie claims, “just a simple business,” but it is also, according to many of its devotees, one of the centers of cultural life in the Philippines and the region.

As a young student and later teacher at Ateneo de Manila University, I would cross onto Manila and buy some of my books at Solidaridad. When I got an Asian Scholarship Foundation grant to do research on South East Asian Literature, I made a pilgrimage (because that was how it sounded like to me) to the bookshop to buy titles I could read before I left for Malaysia. And indeed, I found the poetry books of Shirley Geok-Lin Lim and the novels of Goh Poh Seng.

As Antonio Lopez wrote in Asiaweek Magazine, “Artists and notables gather there to discuss the raging issues of the day or an emerging literary trend. Foreign writers and journalists, too, are always welcome.” The novelist James Hamilton-Patterson told me of the interviews he did with Manong Frankie for his books, the help and generosity given to him abounding.

Among the works published by Solidaridad were Equinox I, an anthology of new English writing by Filipinos (1965) and the Asian PEN Anthology (1966), both edited by Frankie Sionil Jose. I was lucky to buy one of the last copies of both publications. Equinox featured a short story by the UP Comparative Literature major Ishmael Bernal, who had become a famous director by then.

The Asian Pen Anthology, in particular, grew out of the Asian PEN Writers’ Conference, which Manong Frankie organized in Manila in 1962. The book included fiction and poetry from various PEN members in Asia, specifically from Burma (now Myanmar), Ceylon, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand, Taiwan and Vietnam.

The anthology is a watershed: it antedated the publication of literary anthologies where South East Asian and Australian writers are both represented. It also antedated the Asian Writers series that the University of Queensland Press would later publish in Australia.

The anthology also foreshadowed the international reputation of writers Nick Joaquin (Philippines) and Yukio Mishima (Japan). Joaquin’s “May Day Eve” deals with our Hispanic past by delineating the tensions between Roman Catholicism and indigenous cultures, the social division and gender relations during the feast day of Saint John the Baptist in Manila before the Second World War.

On the other hand, Mishima’s “Three Million Yen” is a narrative about a twisted, penny-pinching couple at a local Japanese amusement park. In unblinking terms, it shows the sequence of events that lead them to perform sexual acts before a group of old women for the money.

What is even more interesting is that both stories have two focal characters. Out of desperation, both couples end up performing what can be considered shocking sexual behavior as antidotes to despair. In these stories, Joaquin and Mishima succeed in breaking new ground as far as ”Asian literary trends” and production are concerned.

Between 1965 and 1966, Manong Frankie established Solidarity, a pioneering journal that advanced the understanding of South East Asia and the sense of it as a region. It was a cultural, intellectual and literary quarterly. It succeeded Comment, which had stopped publication when Manong Frankie went to Hong Kong.

The Congress for Cultural Freedom gave Manong Frankie $10,000 a year to print the quarterly magazine. Over three years, he increased its frequency until it became a monthly, through subscriptions. In 1967, when it was charged that the Congress for Cultural Freedom received funds from the US Central Intelligence Agency, the Congress disbanded and regrouped as the International Association for Cultural Freedom, funded by Ford Foundation. This must be where all the allegations about Manong Frankie being a “CIA spy” came from.

Solidarity continued to receive funding until 1972, but it had been reduced to $8,000 annually. However, the magazine thrived, reaching a peak of 8,000 copies per issue. In 1968 the Dept. of Education bought a subscription for 3,000 copies and gave them to the public schools, a wise move that should be replicated today. But Solidarity suffered in 1972, when the department cut the subscription and channeled the funds to another magazine.

Undaunted, Manong Frankie subsidized the journal through the proceeds from his bookshop until 1977, when he could no longer meet production costs. In 1980, he received the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Literature for his writing, his publishing and for being what Edwin Thumboo called “the first genuine South East Asian.” He was writing a weekly column for Philippine STAR before he passed away this Thursday. Farewell, Manong Frankie.

* * *

Email: danton.lodestar@gmail.com

Danton’s translation of “Banaag at Sikat” by Lope K. Santos has been published by Penguin Books as “Radiance and Sunrise.”

- Latest

- Trending