When graft watchdogs are starved, toothless

August 11, 2004 | 12:00am

Since 1955 the Philippines has passed close to a dozen laws against corruption. Administrations put up as many antigraft agencies, and all Presidents vowed to clean the bureaucracy. Yet RP today ranks fourth in Transparency International’s list of most dishonest countries in Asia. By contrast 30 years ago Hong Kong’s was ranked among the most corrupt. Today it is second to Singapore as most upright.

HK’s cleanup success and RP’s failure lie mainly in the size of the watchdog guarding the bureaucracy. The World Bank noted that HK’s bureaucracy is all of 150,000 personnel. Its Independent Commission Against Corruption has a staff of 1,060, for a ratio of 1:142 civil servants. ICAC’s graft investigators alone number 800, or 1:2,000. It has 200 men for community relations, and 60 for graft prevention.

RP has 1.4 million civil servants. The Ombudsman and the Presidential Anti-Graft Commission have a combined force of 1,000, for a ratio of 1:1,400. The Ombudsman has 96 investigators, a three-fold jump from 37 before 2003. PAGC has another 11; the Transparency Group under the Malacañang chief of staff, eight; and six departments, 30. With a total of 145 investigators, RP’s ratio is 1:10,000.

In short, HK’s watchdog is five times bigger than RP’s, in relation to their bureaucracies.

Size depends on the watchdog food. HK’s ICAC was born in 1974 with a budget of $10 million, when its GDP was $16.9 billion, while RP’s was $23.2 billion. ICAC funding has since risen to $90 million (P5 billion) in 2003, reflecting a per capita spending of $15 (P825) to nab government cheats.

RP’S watchdog is starved. The Ombudsman’s budget in 2003 was only P481.4 million. The PAGC had P18.6 million. The Transparency Group and deputies in six departments had P15 million. With the total of P515 million, RP spends a mere P8 per capita for honesty, compared to HK’s P825.

There is reason to study per capita spending against graft in relation to GDP. The cleaner the government, the brisker its economy, due to higher investments and tax collections for infrastructures.

Bigger spending determines the watchdog’s bite. HK’s ICAC works on 3,000 cases a year. At the onset, 1974-1985, it concentrated on lifestyle checks of policemen and high officials, since it was the easiest way to spot grafters. Today ICAC also covers corporate fraud. Prosecution is handled by the justice department, which had a $379-million (P2.7-billion) budget in 2003. The conviction rate that year was 79 percent, or 330 of the 416 ICAC investigations.

RP’s watchdogs, skinny, underfed and toothless, have no bite. All prosecutions with the Sandiganbayan have to be done by the Ombudsman with only 104 trial lawyers, half of them recruited only in late 2003. Its case load that year was a staggering 7,695. The conviction rate was thus a dismal six percent before 2003, jumping to ten percent today. The PAGC, focusing only on presidential appointees, punished 54 out of 1,075 officials investigated, or five percent. The Transparency Group and its deputies in the finance department charged 20 officials who failed lifestyle checks based on the 1955 law; the Ombudsman upheld ten of them.

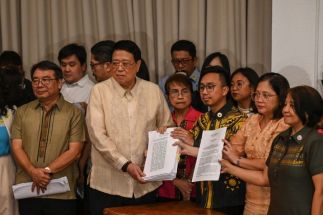

Palace chief of staff Rigoberto Tiglao presented the figures last week to the Legislative-Executive Development Advisory Council, composed of the President, the Vice President, the Senate President, the House Speaker, selected Cabinet members, and the majority and minority leaders of both chambers of Congress. He admitted that the high dismissal rate of graft cases is due to insufficiency of evidence. This, in turn, is due to the scarcity of investigators to build airtight cases. RP’s tough antigraft laws thus prove to be weak deterrents. Corruption becomes a low-risk, high-reward crime.

The weakness, Tiglao pointed out, is in law enforcement. The PAGC and the Transparency Group tried to replicate ICAC’s success rate with its lifestyle checks. With limited budgets, the two groups first gathered the Statements of Assets and Liabilities of all national government employees and officials. Tapping the Commission on Audit, the National Police and the Intelligence Service of the Armed Forces, they then investigated officials against whom complaints had been filed before the PAGC. Only ten of 175 cases prospered, at a cost of P100,000 each, although 46 are still ongoing. And only because six undersecretaries from the Departments of Finance, Agrarian Reform, Health, Public Works, Natural Resources and Education pitched in extra time.

From the limited success arose a proposal to LEDAC: get Congress to expand the Ombudsman’s powers to include periodic lifestyle checks on all career employees, and to increase the number of investigators to ICAC’s ratio. Simultaneously, for the PAGC to continue the checks on presidential appointees. And naturally, to increase the budgets of both agencies.

Tiglao’s proposal was in response to President Gloria Arroyo’s order to officers to "craft enforceable, doable – not motherhood – anticorruption programs." She had said so in a speech early this year before the Bishops’-Businessmen’s Conference. She followed it up in April with the formation of a Presidential Commission on Values Formation, with six members and a chairman with the rank of presidential adviser. In June Mrs. Arroyo expanded the membership to ten, with her sitting as chairwoman.

The Commission will intensify the drive against corruption, and find ways to supplant patronage politics, apathy and mendicant attitudes in government with the values of honesty, modesty and efficiency. Its operating arms, for the meantime, will be the PAGC and the Transparency Group, along with the department deputies. It comes in the midst of efforts by the Administration to pass new taxes and improve collections. Timely so, because corruption and incompetence are the most repeated arguments against new taxes and for evasion.

Catch Sapol ni Jarius Bondoc, Saturdays at 8 a.m., on DWIZ (882-AM).

E-mail: [email protected]

HK’s cleanup success and RP’s failure lie mainly in the size of the watchdog guarding the bureaucracy. The World Bank noted that HK’s bureaucracy is all of 150,000 personnel. Its Independent Commission Against Corruption has a staff of 1,060, for a ratio of 1:142 civil servants. ICAC’s graft investigators alone number 800, or 1:2,000. It has 200 men for community relations, and 60 for graft prevention.

RP has 1.4 million civil servants. The Ombudsman and the Presidential Anti-Graft Commission have a combined force of 1,000, for a ratio of 1:1,400. The Ombudsman has 96 investigators, a three-fold jump from 37 before 2003. PAGC has another 11; the Transparency Group under the Malacañang chief of staff, eight; and six departments, 30. With a total of 145 investigators, RP’s ratio is 1:10,000.

In short, HK’s watchdog is five times bigger than RP’s, in relation to their bureaucracies.

Size depends on the watchdog food. HK’s ICAC was born in 1974 with a budget of $10 million, when its GDP was $16.9 billion, while RP’s was $23.2 billion. ICAC funding has since risen to $90 million (P5 billion) in 2003, reflecting a per capita spending of $15 (P825) to nab government cheats.

RP’S watchdog is starved. The Ombudsman’s budget in 2003 was only P481.4 million. The PAGC had P18.6 million. The Transparency Group and deputies in six departments had P15 million. With the total of P515 million, RP spends a mere P8 per capita for honesty, compared to HK’s P825.

There is reason to study per capita spending against graft in relation to GDP. The cleaner the government, the brisker its economy, due to higher investments and tax collections for infrastructures.

Bigger spending determines the watchdog’s bite. HK’s ICAC works on 3,000 cases a year. At the onset, 1974-1985, it concentrated on lifestyle checks of policemen and high officials, since it was the easiest way to spot grafters. Today ICAC also covers corporate fraud. Prosecution is handled by the justice department, which had a $379-million (P2.7-billion) budget in 2003. The conviction rate that year was 79 percent, or 330 of the 416 ICAC investigations.

RP’s watchdogs, skinny, underfed and toothless, have no bite. All prosecutions with the Sandiganbayan have to be done by the Ombudsman with only 104 trial lawyers, half of them recruited only in late 2003. Its case load that year was a staggering 7,695. The conviction rate was thus a dismal six percent before 2003, jumping to ten percent today. The PAGC, focusing only on presidential appointees, punished 54 out of 1,075 officials investigated, or five percent. The Transparency Group and its deputies in the finance department charged 20 officials who failed lifestyle checks based on the 1955 law; the Ombudsman upheld ten of them.

Palace chief of staff Rigoberto Tiglao presented the figures last week to the Legislative-Executive Development Advisory Council, composed of the President, the Vice President, the Senate President, the House Speaker, selected Cabinet members, and the majority and minority leaders of both chambers of Congress. He admitted that the high dismissal rate of graft cases is due to insufficiency of evidence. This, in turn, is due to the scarcity of investigators to build airtight cases. RP’s tough antigraft laws thus prove to be weak deterrents. Corruption becomes a low-risk, high-reward crime.

The weakness, Tiglao pointed out, is in law enforcement. The PAGC and the Transparency Group tried to replicate ICAC’s success rate with its lifestyle checks. With limited budgets, the two groups first gathered the Statements of Assets and Liabilities of all national government employees and officials. Tapping the Commission on Audit, the National Police and the Intelligence Service of the Armed Forces, they then investigated officials against whom complaints had been filed before the PAGC. Only ten of 175 cases prospered, at a cost of P100,000 each, although 46 are still ongoing. And only because six undersecretaries from the Departments of Finance, Agrarian Reform, Health, Public Works, Natural Resources and Education pitched in extra time.

From the limited success arose a proposal to LEDAC: get Congress to expand the Ombudsman’s powers to include periodic lifestyle checks on all career employees, and to increase the number of investigators to ICAC’s ratio. Simultaneously, for the PAGC to continue the checks on presidential appointees. And naturally, to increase the budgets of both agencies.

Tiglao’s proposal was in response to President Gloria Arroyo’s order to officers to "craft enforceable, doable – not motherhood – anticorruption programs." She had said so in a speech early this year before the Bishops’-Businessmen’s Conference. She followed it up in April with the formation of a Presidential Commission on Values Formation, with six members and a chairman with the rank of presidential adviser. In June Mrs. Arroyo expanded the membership to ten, with her sitting as chairwoman.

The Commission will intensify the drive against corruption, and find ways to supplant patronage politics, apathy and mendicant attitudes in government with the values of honesty, modesty and efficiency. Its operating arms, for the meantime, will be the PAGC and the Transparency Group, along with the department deputies. It comes in the midst of efforts by the Administration to pass new taxes and improve collections. Timely so, because corruption and incompetence are the most repeated arguments against new taxes and for evasion.

BrandSpace Articles

<

>

- Latest

- Trending

Trending

Latest

Trending

By BABE’S EYE VIEW FROM WASHINGTON D.C. | By Ambassador B. Romualdez | 10 hours ago

By IMMIGRATION CORNER | By Michael J. Gurfinkel | 10 hours ago

Recommended