The utopian paranoia of The Village

August 22, 2004 | 12:00am

His Hollywood blockbusters notwithstanding, director M. Night Shyamalan has appeared to be the favorite whipping boy of movie critics — well, at least since 1999’s blockbuster success The Sixth Sense. One writer opined: "Sometimes an early huge success can wind up boxing its maker into a corner– and that may have happened with Shyamalan after The Sixth Sense."

Truth be told, the Indian-born, Philadelphia-raised director is partly to blame for the critical fallout. His subsequent films Unbreakable and Signs both again showcased the allure of the surprise ending and ran it to the ground. One might even argue that these flicks were only saved by the stars who agreed to appear in them. I mean, if Mel Gibson wasn’t in Signs, would we have sat through a yawner of a movie?

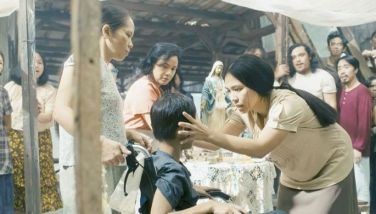

The same promise of a twisted ending lurks just beneath the surface of The Village, Shyamalan’s latest offering. Overtly a monster movie, we are prepped and conditioned right off the bat — from the Blair Witch-esque treatment of the opening credits to the actual first scene (a funeral). The stage is set for some good-ol’-fashioned screaming, all right.

The carefree, spartan life of the villagers of turn-of-the-century (two centuries ago, in fact) Covington Woods merely provides a fitting innocence that lends itself conveniently to superstitious beliefs and is a perfect springboard for a monster-iffic tale.

But lest we forget, The Village is a love story first, bogeyman tale second. At least Shyamalan shines in his development of the story of our blind heroine Ivy Walker (Bryce Dallas Howard) and her introverted knight in drab armor, Lucius Hunt (Joaquin Phoenix). Phoenix seems the perfect fit for Shyamalan’s flicks as the director loves quiet intensity – going for visual drama as opposed to long character dialogues. Painfully withdrawn, Lucius manages to hide his ever-growing affection for Ivy – the strongest and most interesting character in The Village’s smattering of stereotypes and standards: the idiot wildcard Noah Percy (Adrien Brody); the quasi-minister, benevolent leader Edward Walker (William Hurt); and the upstanding, strong maternal figure Alice Hunt (Sigourney Weaver).

All told, The Village is a stew of movies Blair Witch Project, Harry Potter, and Lord of the Rings –and maybe a pinch of Little Red Riding Hood.

Covington’s citizens live their lives happily and simply — yet always in mortal fear of two things: "Those We Don’t Speak Of" (Voldemort, perchance?) that lie just beyond the treeline, and the "towns," "wicked places where wicked people live."

A witch trial could be thrown seamlessly into this Pilgrim-esque diorama, except for the fact that Covington’s citizens are not violent. In fact, each of the town "elders" had previously suffered a tragedy. Violence – the evil that men do – is exactly what drove them into the woods. Now, this utopian settlement of livestock, big ears of corn and people averse to the color red ekes out a living bestowed and cursed with the lack of modern convenience (hint, hint).

There is some Machiavellian self-righteousness in the way the elders impose their will. There is no curfew, no Bible belt, no terrorizing the kids. Nope, they have their bogeyman for that in the bedroom closet that is the Covington forest.

The slow motion sequences, the frenetic violins, the superlative cinematography are all vintage Shyamalan. He doesn’t care much for sleek cuts and quick scenes – preferring us to join him in introspective meandering. He doesn’t just show us the emotion – he wants us to wallow in it. We see Ivy’s overwhelming love for Lucius as she declares to her father gravely: "I’m in love." It’s not a plea, but a declaration of certainty and inevitability. We witness Lucius’ only display of passion when he professes to love Ivy as they sit on the porch of the Walker home.

In one watershed scene, Ivy is led by her dad to a disused old shed. "Do your best not to scream," he says, and reveals a terrible secret.

I’d say the same thing to moviegoers. Indeed, try your gosh-darnedest not to scream. You’ll be kicking yourself in the shins later for it.

Truth be told, the Indian-born, Philadelphia-raised director is partly to blame for the critical fallout. His subsequent films Unbreakable and Signs both again showcased the allure of the surprise ending and ran it to the ground. One might even argue that these flicks were only saved by the stars who agreed to appear in them. I mean, if Mel Gibson wasn’t in Signs, would we have sat through a yawner of a movie?

The same promise of a twisted ending lurks just beneath the surface of The Village, Shyamalan’s latest offering. Overtly a monster movie, we are prepped and conditioned right off the bat — from the Blair Witch-esque treatment of the opening credits to the actual first scene (a funeral). The stage is set for some good-ol’-fashioned screaming, all right.

The carefree, spartan life of the villagers of turn-of-the-century (two centuries ago, in fact) Covington Woods merely provides a fitting innocence that lends itself conveniently to superstitious beliefs and is a perfect springboard for a monster-iffic tale.

But lest we forget, The Village is a love story first, bogeyman tale second. At least Shyamalan shines in his development of the story of our blind heroine Ivy Walker (Bryce Dallas Howard) and her introverted knight in drab armor, Lucius Hunt (Joaquin Phoenix). Phoenix seems the perfect fit for Shyamalan’s flicks as the director loves quiet intensity – going for visual drama as opposed to long character dialogues. Painfully withdrawn, Lucius manages to hide his ever-growing affection for Ivy – the strongest and most interesting character in The Village’s smattering of stereotypes and standards: the idiot wildcard Noah Percy (Adrien Brody); the quasi-minister, benevolent leader Edward Walker (William Hurt); and the upstanding, strong maternal figure Alice Hunt (Sigourney Weaver).

All told, The Village is a stew of movies Blair Witch Project, Harry Potter, and Lord of the Rings –and maybe a pinch of Little Red Riding Hood.

Covington’s citizens live their lives happily and simply — yet always in mortal fear of two things: "Those We Don’t Speak Of" (Voldemort, perchance?) that lie just beyond the treeline, and the "towns," "wicked places where wicked people live."

A witch trial could be thrown seamlessly into this Pilgrim-esque diorama, except for the fact that Covington’s citizens are not violent. In fact, each of the town "elders" had previously suffered a tragedy. Violence – the evil that men do – is exactly what drove them into the woods. Now, this utopian settlement of livestock, big ears of corn and people averse to the color red ekes out a living bestowed and cursed with the lack of modern convenience (hint, hint).

There is some Machiavellian self-righteousness in the way the elders impose their will. There is no curfew, no Bible belt, no terrorizing the kids. Nope, they have their bogeyman for that in the bedroom closet that is the Covington forest.

The slow motion sequences, the frenetic violins, the superlative cinematography are all vintage Shyamalan. He doesn’t care much for sleek cuts and quick scenes – preferring us to join him in introspective meandering. He doesn’t just show us the emotion – he wants us to wallow in it. We see Ivy’s overwhelming love for Lucius as she declares to her father gravely: "I’m in love." It’s not a plea, but a declaration of certainty and inevitability. We witness Lucius’ only display of passion when he professes to love Ivy as they sit on the porch of the Walker home.

In one watershed scene, Ivy is led by her dad to a disused old shed. "Do your best not to scream," he says, and reveals a terrible secret.

I’d say the same thing to moviegoers. Indeed, try your gosh-darnedest not to scream. You’ll be kicking yourself in the shins later for it.

BrandSpace Articles

<

>

- Latest

- Trending

Trending

Latest

Trending

Latest

Recommended