Walking the fine line between fidelity and license

October 26, 2002 | 12:00am

Film review: The Importance of Being Earnest

Film review: The Importance of Being Earnest

An adaptation walks the fine line between fidelity and license. The goal is to make the transition from the one medium to the other as smooth as possible while retaining the spirit of the original – a target that is far easier to miss than hit.

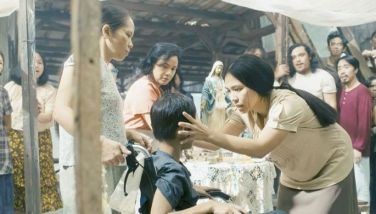

Such seems to be case with Oliver Parker’s adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, currently playing at the Greenbelt cinema in time for what would have been the playwright’s 148th birthday. (He was born Oct. 16, 1854.) While it cannot be called a failure, it has less of the exuberance of either Parker’s previous attempt at adapting Wilde (An Ideal Husband) or, indeed, the mere text of the play itself.

The basic situation is still "Bunburying," that is, the invention of a false identity to escape the pressures of the real one. Tired of taking the high moral tone as guardian of Cecily Cardew (Reese Witherspoon) in his country estate, Jack Worthing (Colin Firth) invents Ernest, a ne’er-do-well brother whose "escapades" invariably take him to the city. His true intention, however, is to see his love Gwendolyn Fairfax (Frances O’Connor), who knows him by the name Ernest.

Meanwhile, his friend Algernon Moncrieff (Rupert Everett), Gwendolyn’s cousin, visits a Mr. Bunbury, an imaginary invalid whose illnesses conveniently occur whenever his (Moncrieff’s) creditors call or when his "Wagnerian" Aunt Augusta (Dame Judi Dench) invites him to dinner. When Algernon goes Bunburying as Ernest in Jack’s country estate, the complications begin. The entanglements increase when Gwendolyn, forbidden by her aunt to marry Jack because of his uncertain origins (he was found in a handbag at Victoria Station), steals away from the city to Jack’s estate – only to find Cecily already engaged to an Ernest Worthing.

The situation, in its very absurdity, is gay enough, but Parker seems bent on improving it. The results, however, are uneven – a case, it seems, of too many birds spoiling the broth or, more apropos, of too many feathers ruining a Gainsborough hat. Among his additions are flashbacks dramatizing what is merely described, fantasy sequences showing Cecily and Algernon/Ernest in Pre-Raphaelite poses, and the expansion of the romance between the minor characters Ms. Prism and Dr. Chasuble. Many of these embellishments stick out as such: embellishments – excessive, extraneous, and expungable. Near egregious is Parker’s revision of the play’s final revelation.

This is a letdown after An Ideal Husband, where Parker’s departures enriched his source. In one scene, for instance, he has Wilde step in as a character commenting on a performance of Earnest, thereby cleverly bringing to the surface the play’s theme of secret identity and coaxing viewers to draw the connections between play and playwright. Compared to that metafictive coup, the butt tattoo scenes in his adaptation of Earnest seem low.

As though to make up for tampering with Wilde, Parker retains more lines from the play than he does in An Ideal Husband. The bon mot, after all, is the hallmark of Wilde. Listen:

1. "All women become like their mothers. That is their tragedy. No man does. That is his."

2. "I never travel without my diary. One should always have something sensational to read in the train."

3. "In matters of grave importance, style, not sincerity, is the vital thing."

4. "It is absurd to have a hard and fast rule about what one should read and what one shouldn’t. More than half of modern culture depends on what one shouldn’t read."

5. "Never speak disrespectfully of Society, Algernon. Only people who can’t get into it do that."

Wit, however, works like the flash, and the more expansive medium of film, with its shifts of settings (from parlor to sleazy saloon to garden to street), slows down what should be ripostes rapidly exchanged in the intimacy of a drawing room.

However, the film should be of interest to followers of Wilde for two reasons. First, it restores the omitted "Grisbsy episode." (Wilde had originally conceived Earnest in four acts, cutting it down to three at his producer’s suggestion.) In this scene, a Mr. Grisbsy of Parker and Gribsby, Solicitors arrives at the country estate with a writ of arrest against Algernon, who disguised as Ernest, has left a huge debt unpaid. It is up to Jack to either expose or save him.

The inclusion of the scene heightens the tension between the two Bunburyists. However, the film stops short of mining its thematic value, omitting the detail that Gribsby is also Parker and therefore is as much an imposter as either Jack or Algernon. ("I am both, sir. Gribsby when I am on unpleasant business, Parker on occasions of a less serious kind.")

Second, the film sets into music, albeit anachronistic jazz music, a poem by Wilde. In the play, the two friends, their subterfuge exposed, whistle "some dreadful popular air from a British opera" to try to win back their loves, both of whom are fixated on the name Ernest. By replacing the air with Wilde’s Serenade, Parker slyly jabs at the very writer he is paying homage to, a writer whose lyrics rarely rose above doggerel. (The scene also reminds viewers of Everett’s days as a singer.)

Despite its shortcomings, however, this is delightful entertainment. Adding to the enjoyment, certainly, is that, unlike his contemporaries, we now see Wilde’s pun as more than just a critique of "earnestness" or the sham moral seriousness of the late Victorian. The Dictionary of Euphemism tells us that "earnest" was a euphemism for homosexual in the 19th century. Parker puts forward the suggestion when he shows – and this is perhaps his most felicitous rewriting of Wilde – Algernon and Jack picking violets.

When the last line is spoken – "I’ve now realized for the first time in my life the vital importance of being earnest" – we can imagine him nudging us in the side and Wilde, in his velvet coat, winking at us from paradise. One hundred years since his ignominious death, we finally get the joke – and are tickled. That is gratification enough – for us and, it is hoped, for him.

BrandSpace Articles

<

>

- Latest

- Trending

Trending

Latest

Trending

Latest

Recommended

Exclusive

Exclusive