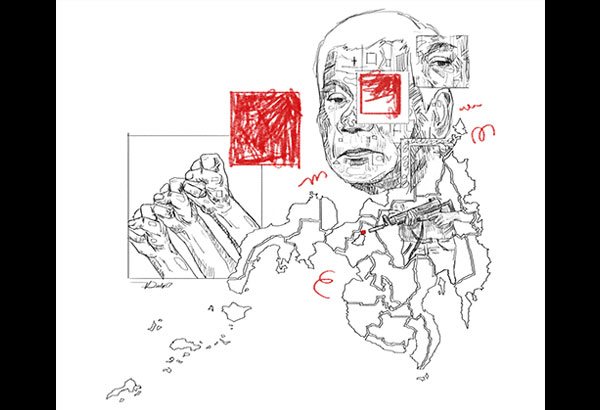

On the day I had agreed to lead my balikbayan relatives on a Mindanawon excursion, it was the first morning of Duterte’s martial law. We had planned it way in advance, but waking up to the news of martial law threw us into limbo. What to do?

The sun was warm, the skies were clear, and the birds were singing. The tamban vendor sold his wares on his loud Kawasaki while the smell of hot pandesal wafted in the early morning air. But martial law stared us in the face. Apart from asking whether the declaration was an overreaction or not, we had to wonder: “All of Mindanao?”

I reviewed the Tuesday night press conference in Russia to look for answers. When Foreign Affairs Secretary Alan Cayetano talked about how severely the President thought over his decision to declare martial law, the first example that came into his head was their lamenting over how martial law would affect tourism. Either Cayetano was downplaying the gravity of declaring martial law or he was throwing shade, his facts and priorities unclear, and was thinking of Mindanao only as a tourist destination and nothing more.

But the declaration could not be any less personal to us. We reside and make our lives here in the Land of Promise. And on that Wednesday morning, we were also the tourists Cayetano & Co. supposedly thought of, hoping to travel 200 kilometers southwest to Surigao del Sur from Agusan del Norte. But more than that, the declaration somehow hit a raw nerve and we couldn’t pinpoint exactly why. That the declaration covered all of Mindanao when the fighting was practically isolated in Marawi — and the fact it was declared over Mindanao alone — left a bad taste in our mouths, like there was more to it than the 60-day shadow of a dictatorship past.

PNP checkpoints

Seven kilometers from our house, our van encountered its first PNP checkpoint. A truckload of logs which might have contained booty flew past them while we, on the other hand, had to roll our windows down, open our doors, and give our kindest smiles for the police. We would encounter half a dozen more checkpoints on our trip down south with none of them finding anything unusual with our group of typical bakasyonistas; towels draped over our heads, dark glasses covering our drooping eyes, and Styrofoam boxes loaded at the back. Apart from their camouflage uniforms, their rugged boots, the heavy carbine magazines loaded on their vests, and the assault rifles they held with both hands and strapped crosswise over their shoulders, the military men likewise exhibited nothing unusual.

They had a script. “Aha mo gikan?” (Where did you come from?) “Aha mo padulong?” (Where are you going?) We would reply smiling, they would apologize for the inconvenience and would welcome us to the town where they were based. Many of them were Tagalogs stationed here, their accents giving them away. Surprisingly, other checkpoints which weren’t manned before — like the ones in Lianga, a town supposedly infested with rebels — remained unmanned for Day 1 of martial law. Some checkpoints were merely 500 meters apart and they would survey us twice, a redundancy similar to bag checkers in Manila malls linked to one another. Military rule, I thought, thrived on these eerie loopholes which espoused uncommon logic. This was not the first time I encountered an unusual number of military checkpoints in Mindanao.

Three years ago, with plans to take a boat to Siargao but stranded in mainland Mindanao by typhoon Ruby, my friend and I decided to travel westward instead, to Marawi. The trip there was cold and foggy, with the road from Iligan climbing up to Marawi having no streetlights; the houses on the sides of the road were lit only by candles and kerosene lamps. More than twice, persons — children, an old lady, and groups of teenagers — popped up right in front of our car, made visible by our headlights only a few meters before we would have run them over. There were checkpoints set up by the Armed Forces and checkpoints set up by the MILF. None of them caused us any trouble.

Arriving in Marawi

When we got to Marawi, we were welcomed by tall cheesecloth banners with black letters in ALL CAPS spray-painted on them. Hung onto wires, these streamers announced a 10 p.m. curfew. With nighttime crawling in, people avoided us whenever we tried asking for directions. We were looking for “the best restaurant in town.” We felt our spirits shrink and, in less than hour, at around 8 p.m., we found ourselves driving back to Iligan.

We later found out that kidnapping stories in Marawi often began with two grown men in an SUV, rolling their windows down and asking for directions from unsuspecting passersby. Needless to say, we fit the bill. It was not that Marawi was full of suspicious characters. It was that we, ourselves, looked like crooks. It was an eye-opener, an odd incident wherein traveling taught us more about ourselves than the place we were visiting.

Surigao del Sur, however, was nothing like that. Outside our van’s windows were banana farms, palm oil plantations, vast plots of coconut trees, remnants of centuries-old dipterocarp forests, and the Pacific Ocean. Many of the people standing by the roads were ready to assist tourists; they even hitchhike. But same as in Marawi, many houses in Surigao del Sur still had no electricity, many lived in decrepit houses beside unfinished roads, and with so little development in the area, it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that many are unemployed or living off low wages. Even without guns — even without the Maute group — there is violence here, one which martial law can hardly fix.

Not all sadness

But to say that it is all sadness in Marawi, in Surigao, and in other parts of Mindanao, would be a crime. One of the common beliefs from where I am sitting now is that here, there is no government, and it’s either we do something about our situation or we flagellate ourselves for doing nothing about it. Indeed, some of the brightest colleagues I am friends with graduated from Marawi. And none of the guests I’ve brought to Surigao ever left unhappy.

Mindanao has many stories to tell. There are many Mindanaos, and the lakes, seas and mountains that divide the region and its people are all witnesses to this. In both beautiful and estranging ways, Mindanao is not a singular entity. Media and government have made this idea too hard for non-Mindanawons to learn, especially for Manileños with whom too much power resides. This is precisely why Duterte’s martial law is painful to us: it paints the entire region in broad strokes and forces us to unite under war’s ugly color. This violence in framing all of Mindanao as a war-torn place is just as debilitating as the violence caused by these pockets of armed conflict.

One would think that a President born and raised in Mindanao wouldn’t be so reckless as to group Mindanawons under the single category of “violent and dangerous.” He would know how different our lives are in Agusan, in Bukidnon, in Dinagat, in Zamboanga, in Lanao, in Davao, etc., etc. But here he is, inflicting pain upon his own kind.

We drove back home after seeing Tinuy-An Falls in Bislig, and swimming at Britania Islands in San Agustin, both in Surigao del Sur. On the first day of martial law, at least 200 tourists were out, including ourselves. We left before sunset and encountered no more checkpoints on the way home. I took this as an affirmation from the military itself. Perhaps, when their Commander-in-Chief wasn’t watching, they also asked, “Why put all of Mindanao under such terror?” There is enough violence here.

* * *

Tweet the author @sarhentosilly