Southeast Asia’s lofty gas plans pose threats to waters rich with marine life

MANILA, Philippines — For 57-year-old Tom Buitizon, the Verde Island Passage is the lifeblood of small fisherfolk like him and of millions living in southern Luzon.

The rich waters support their livelihoods and provide food for their families.

A fisherman for over 25 years, Buitizon experienced the joy of catching as many as 20 kilos of fish many years ago and the struggle of people living on VIP’s shores who hardly find food there these days.

He said a lot has changed—for the worse—since Batangas City became the site of various industries, including fossil gas.

“At present, I can catch only two to three kilos. Sometimes, I’m not keen to venture out to fish because the exhaustion and high cost of gasoline are not worth it,” said Buitizon, who is from San Juan town. He engages in fishing to supplement his income as a local government employee.

Buitizon is worried that the rapid expansion of fossil gas will make pressures in the marine corridor—which is dubbed as the “Amazon of the Ocean”—worse.

Verde Island Passage is home to 60% of all known shore fish species in the world. It is also the site of eight planned gas power plants and seven LNG terminals.

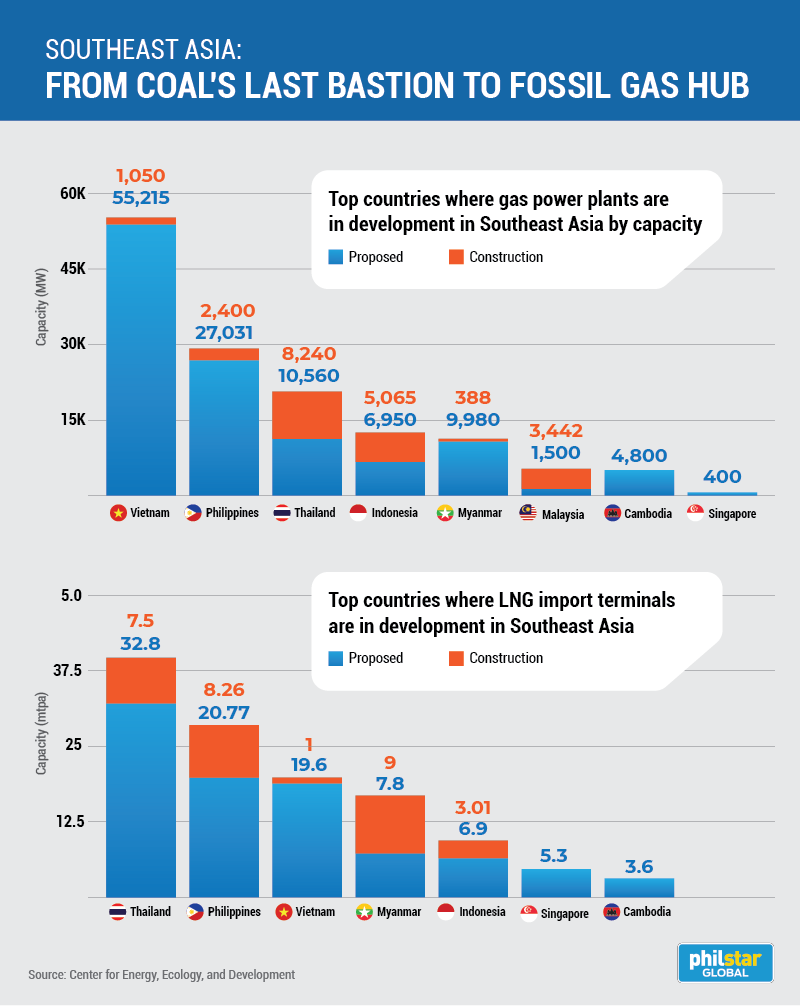

VIP is only one of the marine frontiers in Southeast Asia threatened by gas plans in the region. According to Quezon City-based think tank Center for Energy, Ecology, and Development (CEED), Southeast Asia is swiftly turning from coal’s last bastion to Asia’s fossil gas hub.

In a report released last month, CEED said a massive 138 GW of new gas-fired power plants and 118 liquefied natural gas terminals are being proposed or already being built in the region. Leading the gas expansion in Southeast Asia are Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam—countries that have vast renewable energy potential.

Rich marine biodiversity at risk

The Verde Island Passage lies at the heart of the Coral Triangle, a reef network that includes the waters of Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and East Timor.

While the Coral Triangle occupies just 1.5% of the world’s total ocean area, it represents 30% of the coral reefs on the planet.

But years of industrial development caused serious damage to VIP’s marine ecology. Climate change, illegal fishing, and unsustainable tourism also pose threats to the marine corridor.

A water quality analysis conducted by CEED found “very high” concentrations of key pollutants and heavy metals such as phosphates, chromium, copper, and lead along the coasts of Barangays Ilijan and Dela Paz in Batangas City. A separate CEED study showed the coral cover along the reef fronting the heavily-industrialized areas in Ilijan and Dela Paz was “very low”.

It also found that while fish biodiversity and fish abundance were low in the waters next to the project sites compared to the rest of the Verde Island Passage, fish biomass remained high.

CEED pointed out that sea water intake and discharge from gas plants and terminals may affect water temperature, forcing fish to seek cooler water elsewhere. It added that the increase in shipping activities due to the transportation of LNG will lead to water pollution, sedimentation that can destroy coral reefs, and damage to smaller seacrafts.

If the Verde Island Passage is further damaged by the planned increase in LNG infrastructures, the effects of the destruction may be far-reaching.

“The concept is that biodiversity regions are interconnected with one another and all organisms in the other regions came from [the Verde Island Passage],” said Jayvee Saco, assistant professor from Batangas State University and head of the VIP Center for Oceanographic Research and Aquatic Life Sciences.

“So it could be an escalating effect” he warned, although acknowledging that a study to identify how the population in VIP is connected to population in other regions still needs to be done.

Buitizon, the fisherman, fears that the various kinds of fish in VIP will vanish if the massive development of fossil gas in the area pushes through, and that the next generation will only know about them through books.

“We are not fighting the government. We just want them to understand our concerns and study the effects of this LNG expansion because VIP is home to different kinds of marine species. If this is destroyed, not only the lives of Batangas residents will be miserable, but also those living in other provinces,” he said.

Last month, groups led by Bukluran ng Mangingisda ng Batangas urged the environment department to declare the waters of VIP surrounding the project sites of San Miguel Corp., Linseed-AF&P, and existing gas plants as “non-attainment areas” where no new sources of exceeded pollutants should be allowed to be established.

The Philippine energy department told Philstar.com that the issuance of environmental compliance certificate signifies that a project will not cause significant negative impact, and that it conducts inspections and investigations of proposed gas facilities.

Damage to mangroves in Island of God

On the Indonesian island of Bali, local communities are also resisting the construction of a planned LNG terminal. The project, which will be built in a mangrove forest in Denpasar City, aims to help the government reach its target of accelerating the use of gas.

According to CEED, aggressive LNG terminal buildout can be observed in LNG exporting nations such as Indonesia and Malaysia.

Ida Bagus Setiawan, who heads the energy and mineral resources division of the Bali Province Manpower and Energy and Mineral Resources Office, said the LNG project will provide the top tourist destination with reliable electricity so it will no longer depend on energy sources outside the island.

But locals fear that the planned LNG terminal in Ngurah Rai Forest Park in Sidakarya Village will clear mangroves in the area. Ngurah Rai Forest Park is Bali’s widest mangrove ecosystem that is close to the business and tourism areas.

The dredging of sand for the sea lane is also seen to damage mangroves and other coastal ecosystems. Mangroves provide a number of critical ecosystem services such as serving as a breeding ground for marine species, sequestering carbon dioxide, and reducing the risks of tsunamis.

A pipe for gas distribution will pass through the mangrove area, but the proponent, PT Dewata Energi Bersih, said it will not disturb the mangrove roots. Communities are also concerned that the proposed jetty port for LNG carriers will damage the coral reefs in the area. Bali is part of the Coral Triangle.

“[The LNG terminal] in Bali must be considered again whether there is the potential for major damage if it continues to be cultivated,” said natural resources law observer Ahmad Redi.

IGW Samsi Gunarta, head of Bali Provincial Transportation Service, said dredging can only be carried out if there is a permit as well as a risk-based analysis process, which refers to the results of the environmental impact analysis.

“The permit will not be issued if the requirements in the environmental document cannot be confirmed, and the project can be terminated if this is not fulfilled,” he said.

Lack of public hearing, study

Chana, a coastal town in Songkhla province in southern Thailand, is known for its marine ecosystem, with a majority of its residents relying on fisheries as their main livelihood. A portion of Chana is being developed as an energy industry complex and a deep-water seaport.

At present, southern Thailand is the only region in the country, excluding the Bangkok Metropolitan area, where the demand for electricity surpasses production capacity. To power the gigantic industrial zone, the government is planning to build an energy hub. One of the main infrastructures there is the LNG power plant.

Locals and activists are protesting the project due to the lack of public hearing with residents whose lives and livelihoods will be affected by the industrial development. Constructing the LNG terminal will require the dredging of the seafloor to accommodate massive LNG carriers.

“It’s not about the energy; it’s about conducting a proper public hearing. They have never asked the local people at all, or if they did, they will find a way to obstruct them,” said Supat Hasiwannakit, a medical doctor and one of the activist leaders.

Protests in Chana and Bangkok have led to the arrests of some activists.

The environmental impact assessment conducted by the government showed scant details on how the project could affect Chana’s rich waters. Kua Rittibon, a lecturer with Prince Songkla University, who will conduct a “people's version” of EIA, said that sediments excavated by dredging could be carried by the current and affect coral reefs.

In Vietnam, which leads the region’s planned gas expansion, there are also limited studies on the impacts of gas projects on marine biodiversity and coastal communities. Vietnam has 56.3 GW of fossil gas projects in pre-construction and construction stages.

The lack of understanding about the effects of energy projects could be attributed to the country’s focus on the conservation of ecosystems on land and on lack of public attention to studies about marine issues.

“There is limited research on gas power projects: how will the coastal area be affected, whether the gas power plant will increase the temperature in that area or not. If the temperature increases, how will aquatic species be affected, how does the system use cooling water to discharge waste, etc.,” said Nguyen Manh Ha, director of the Center for Nature Conservation and Development.

While companies in Vietnam have an obligation to disclose their environmental impact assessments, not all firms fully comply with this rule.

“At present, the environmental impact assessment and management of new electric energy projects in Vietnam are completely absent,” Nguyen said.

Fossil future?

Many of the LNG projects in emerging Asia are “highly unrealistic” due to country-level and financial market constraints, said Sam Reynolds, energy finance analyst of US-based think tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

“This is overpromising and under-delivering on a regional scale,” he said.

But as Southeast Asian countries scale up investment in fossil gas infrastructure, measures must be put in place to mitigate the impacts of the projects’ life cycle on the marine environment and the communities.

For Miguel Azcuna, a scientist studying the Verde Island Passage, recognition from international institutions such as the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) can help slow down the “very fast” industrial development in the area.

Increasing the number of marine protected areas in the marine life-rich body of water is also another strategy to mitigate the adverse impacts of industrialization, added Azcuna, an assistant professor from Batangas State University. VIP has 36 MPAs, 24 of which are in Batangas.

In 2017, the Verde Island Passage Marine Protected Area Network and Law Enforcement Network was created. The five provinces that surround VIP—Batangas, Occidental Mindoro, Oriental Mindoro, Marinduque, and Romblon—and national government agencies signed an agreement to protect and conserve the marine corridor.

Present during the signing of the agreement was a representative from Lopez-led power firm First Gen Corp., which built four gas-fired power plants in the area and is currently constructing a floating LNG terminal there.

Muhammad Zainuri, a marine biology expert at Indonesia’s Diponegro University, suggested that companies invest in remediation systems to treat wastewater.

“We need the sea to stay blue, to produce oxygen. Waste is accumulative in nature, so it keeps increasing every year. If it's not handled, it's a problem,” he said.

Experts across the region also emphasized the need for proper assessment of the impacts of projects. Ngo Thi To Nhien, executive director of Vietnam Initiative for Energy Transition, also said that in Vietnam’s cases, where the development of LNG is new, it is necessary that the country learns from the experience of developed nations.

She also stressed that regulations must be reviewed and synchronized to ensure the compliance with actual socio-environmental action plans.

“For project investors, regulations need to include adequate and timely preparation of social and environmental resources, time to implement impact mitigation measures and measures to prevent or respond to adverse events,” Ngo said.

“Government needs to specify inspection or monitoring regulations including a separate and specific report form for LNG to monitor or handle environmental and social issues on land and sea.”

--

Napat Wesshasartar is a photo/video journalist, and writer based in Bangkok, Thailand. His work has been published in National Geographic Thailand, BBC Thai News, and other international media platforms.

Do Thuy Trang has been working as a reporter for Vietnam Law Newspaper, a press agency under the Ministry of Justice, since 2017.

Hartatik is a journalist working at Suara Merdeka, the largest newspaper in Central Java, based in Semarang, Central Java, Indonesia.

This collaborative reporting story was supported by Climate Tracker

- Latest