'Internationally wrongful act': Gov't demands legal remedy for climate change damages at top UN court

MANILA, Philippines — The Philippine government asserted before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on Tuesday, December 3, that countries most responsible for driving climate change are committing an "internationally wrongful act."

It called on these nations to provide reparations, marking one of the Marcos Jr. administration’s boldest statements on climate justice.

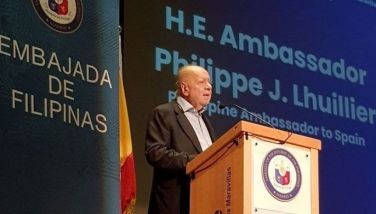

At the landmark climate change hearings in The Hague, Netherlands, Solicitor General Menardo Guevarra emphasized that the Philippines' position is to hold nations accountable for the largest contributions to greenhouse gas emissions.

“The Philippines submits that any act or omission attributable to a state which results or has resulted in anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions over time, thereby causing climate change, is a breach of a state's obligation under international law,” he said.

Guevarra presented the escalating climate challenges faced by the Philippines, including record-breaking heat and increasingly severe storms.

He referred to the recent train of cyclones, many of which were super typhoons, which battered regions with no memory of strong storms. Guevarra also mentioned how the country reached 55°Celsius in May this year. Both have caused several class suspensions.

For 16 consecutive years, the Philippines has been ranked the most disaster-prone country on the World Risk Index, with its score worsening slightly in 2024.

A developed country’s responsibility

Guevarra also said that nations failing to “faithfully conform to their international obligations” under existing laws, conventions and treaties established with the United Nations are committing an “internationally wrongful act.”

“The commission of such internationally wrongful act triggers state responsibility with its necessary consequences, and carries with it the obligation of the responsible state to cease the wrongful conduct and make full reparation therefore,” he said.

Examples of legally binding international agreements include the Paris Agreement and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), adopted by nearly 200 nations.

The Paris Agreement, ratified in 2015, compels countries to cooperate in limiting the rise in global average temperatures to no more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

Meanwhile, the UNFCCC places the burden of responsibility on developed, heavily industrialized countries, as they are the largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions inducing global warming.

As developing countries like the Philippines are disproportionately affected by climate change, Guevarra argued that countries should have the right to “demand the enforcement of remedial actions.”

This could include ceasing the “internationally wrongful act” and obtaining reparations for the damages caused, he added.

An international legal remedy. Drawing on the Philippine legal concept of the Writ of Kalikasan, which safeguards environmental rights, Guevarra suggested that the ICJ consider a similar international remedy.

He said that the Philippines “has no inch of doubt” that international law imposes a broader responsibility on countries contributing to climate change, stressing that these nations can do more to reduce their emissions.

Climate change a threat to global peace and security

Acknowledging that climate change is also caused by goals of economic development, Guevarra said that a country “must operate within a paradigm of non-compromise.”

Meanwhile, Philippine Representative to the UN Carlos Sorreta said that climate change does not only affect the environment but it is also a “serious threat to [the] maintenance of peace and security.”

“Rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and resource scarcity fueled by the climate crisis destabilize regions, exacerbate conflicts, displace peoples, and imperil sovereignty and territorial integrity,” Sorreta added.

Amid threats to its territorial waters, including the West Philippine Sea, Sorreta also said the fundamental role of the 2016 South China Sea Arbitration ruling also mandates protection from “future damage and preservation.”

“States are bound to address the climate crisis within a legal framework that maintains peace and security, respects sovereignty, and upholds human rights,” he said.

The ICJ, in the biggest case on climate change to date, began hearing arguments from 98 countries and 12 international organizations on Monday, December 2.

This followed Vanuatu's request for an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice, seeking clarification on states' legal obligations under international law to protect the climate system, as well as the consequences for failing to uphold these commitments.

The proceedings also come after the 29th Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC, which has faced criticism from several developing nations over the modest 300 billion USD annual climate finance deal by 2035.

Civil society groups have called for at least 1.3 trillion USD for climate adaptation, disaster response and mitigation.

The public hearings at the ICJ will run until December 13.

- Latest