Torture, abuse rampant in Philippine drug detention centers — Amnesty International

MANILA, Philippines — Individuals detained on drug charges in the country are subjected to torture, degrading treatment and other severe human rights violations, a report of the human rights group Amnesty International said.

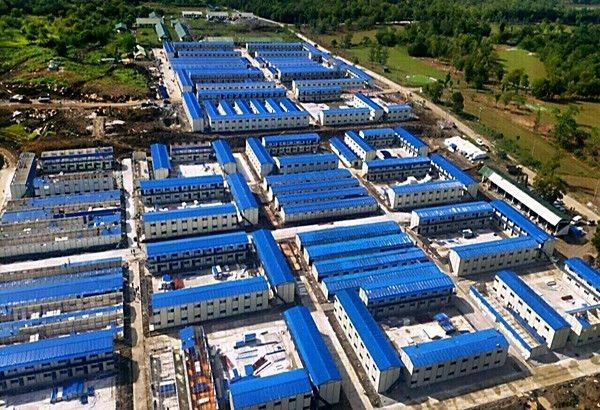

The group said this in a 68-page report released on Thursday, November 28, saying that individuals under “rehabilitation” at government-run drug treatment and rehabilitation centers experience abuses, where “treatment programs” are reportedly punitive rather than therapeutic.

According to the report, individuals under rehabilitation are subjected to non-evidence-based rehabilitation methods, mandatory drug testing and harsh punishments even for minor infractions.

“Drug detention centers are disguised as facilities offering treatment and rehabilitation. In reality, they are places of arbitrary detention where people suffer serious human rights violations that continue even after their release,” Jerrie Abella, Amnesty International’s campaigner in the Philippines, said in a statement.

The release of the report coincided with renewed focus during legislative hearings on abuses committed under former President Rodrigo Duterte’s controversial war on drugs.

“While it is crucial for lawmakers to investigate President Duterte’s role and others' potential involvement in crimes against humanity, the hidden abuses within drug detention centers demand immediate action,” Abella said.

Despite President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.'s promise to shift to a public health and human rights-based approach to drug issues, the report noted that punitive policies remain in place, continuing to criminalize and stigmatize drug users.

On November 12, the government announced a shift in its drug war strategy, focusing on the "supply side" by targeting "big guns" and suppliers rather than drug users.

RELATED: Marcos admin switches gears on drug war: Target suppliers, not users

Torture, unjust punishments

Amnesty International said that many detention facilities are located near police or military bases, where detainees experience physical and psychological abuse.

In one instance, a detainee reported being tortured by police to force a confession of drug use.

He was beaten with a wooden stick, his fingers squeezed with bullets and his face burned with chili sauce before being sent to a detention center.

Individuals are also imposed degrading penalties with prolonged exercises such as being forced to face the wall for hours.

Forced plea bargains

Individuals before being sent to detention centers are reportedly subjected to forced plea bargaining agreements where they are asked to plead guilty for alleged drug crimes.

Several individuals interviewed by Amnesty International shared that plea bargaining gave them a small sense of hope for regaining their freedom.

By accepting plea deals, they could spend six months to a year in drug detention centers rather than endure protracted trials that might result in years of imprisonment.

However, drug-policy reform group NoBox Executive Director Inez Feria pointed out that plea bargains are not “voluntary” as it is a court order.

“Rehabilitation is not voluntary because it’s a plea bargain, because it’s a court order. How can you call them voluntary when people accessing them are people on the drug watch lists, people who are threatened if they don’t go, people who are being visited in their homes, if it is court-mandated?” Feria said, according to the report.

One individual interviewed, who was arrested in 2016, said she chose rehabilitation over jail time.

"The justice system is so rotten that I just chose rehabilitation instead of being jailed without knowing when I would be released,” the individual interviewed by the rights group said.

Post-release surveillance

Even after release, individuals face intrusive aftercare programs requiring regular check-ins and unannounced drug tests for 18 months.

According to Amnesty International, refusal of the individuals to comply is interpreted as relapse, often accompanied by threats of re-arrest.

“I was told by social workers that they will advise the court that I have really changed and that I am showing good behavior, because if not, they can ask that I be brought back to rehabilitation. If I don’t report, they can ask that an arrest warrant be issued against me,” an individual, who has been interviewed by the rights group.

Call for reform

Amnesty International said the government shall “move from punitive and harmful responses towards evidenced-based initiatives” in order to respect the dignity of people and to address the roots of drug use.

“The compulsory and punitive nature of the current model should be discontinued and the government should work to ensure that drug-related services are evidence-based, voluntary, and age- and gender-appropriate, while prioritizing community settings rather than institutions,” the report read.

“The Philippine government must also work towards addressing the stigma and discrimination around the use of drugs. The international community must increase the financial and technical support provided to civil society organizations that prioritize peer-led and evidence-based harm reduction initiatives and respond to the needs of people who use drugs,” it added.

Philippine laws concerning illegal drugs are governed by Republic Act 9165 or the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002.

The law defines and penalizes everything related to illegal drugs where the penalty is usually in the form of jail time or individuals might undergo rehabilitation.

The government data estimates 6,000 deaths during the implementation anti-drug campaign of the Duterte administration.

However, an international human rights group estimates up to 30,000 fatalities which usually consist of small-time drug pushers and users.

- Latest

- Trending