American humanitarian worker saves money for NGO

MANILA, Philippines — To scrimp on money, an American humanitarian worker had to consume “chippies” and soft drinks to save on meal allowances and enable a non-government organization in the Philippines to address the mental health of victims of armed conflict.

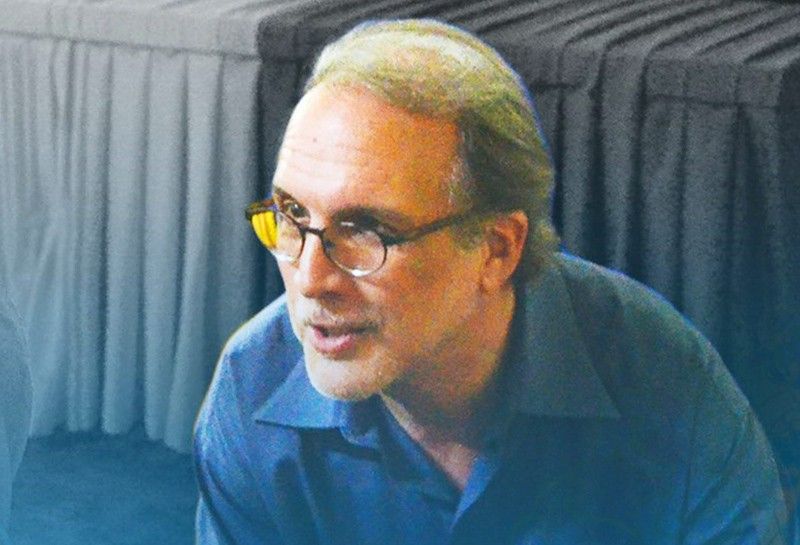

Steven Muncy, Community and Family Services International (CFSI) executive director, recalled the humble roots of his organization which offers psycho-social services to victims of displacement in conflict areas.

Muncy’s mission earned him this year’s Ramon Magsaysay Foundation award, Asia’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize.

The CFSI started out as the Community Mental Health Services, an organization Muncy established in 1981 with the help of the Norwegian government and United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

During the initial stages of the CMHS formation, Muncy scrimped on meal allowances to be able to train volunteers.

“I didn’t want to get money from the Philippine government. Many of my meals were chippies and Coke, I was famous for that,” he said in an interview on Friday.

At the same time, Muncy said he had to train volunteers and even refugees to “help other refugees” and become “helpers of their own people.”

“I write grant proposals like crazy at night trying to raise money,”he added.

The organization was renamed CFSI in 1989, committed to “the lives, wellbeing and dignity of people uprooted by persecution, armed conflict, disasters and other exceptionally difficult circumstances,” according to the Ramon Magsaysay Foundation’s profile on Muncy.

“The CSFI-service style is you first need to talk to the people. You need to listen. We went to different evacuation centers and talked to the people who experienced first hand conflict and displacement, and in so doing we heard of many people who felt so bad about the loss that they were distressed and angry,” Muncy said.

When he first started as a refugee volunteer worker in the Philippines in 1980, Muncy noticed that mental health was not given priority by donors, who focused on providing meals, mosquito nets, books and other materials for refugees in the Philippines.

During his rounds at a refugee camp in Morong, Bataan, which served as a haven for those displaced by the Vietnam War and the genocide in Cambodia, Muncy noticed that refugees exhibited symptoms of trauma and anxiety brought about by their experience of war and persecution.

“I walk the camp every day, and I (saw) a pattern that refugees would come out of their barracks, try to practice English, and in many cases try to convey something was very wrong. And often I would be pulled in and be presented with a very difficult situation,” Muncy said.

He said women had opened up to him about being raped by pirates at sea, and then rejected or beaten up by their husbands who considered them “impure.”

He also heard first-hand accounts of Cambodians who were traumatized since fleeing the genocide led by the Khmer Rouge.

“I have never met an intact Cambodian family. Every family lost someone to genocide. When you move from a place like that, all things you’ve been holding inside your head come to the fore, so people would get anxious and display evidence of trauma,” Muncy said.

It was his “calling” to assist these refugees since he read about their plight in the newspapers after graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Virginia in 1979.

He chose the Philippines as site for his mission work after enlisting as a Baptist journeyman that brought him as a volunteer to the Philippine Refugee Processing Center in Morong, Bataan.

- Latest

- Trending