'Wiretapping' or 'ambush' interview? Here's what the Anti-Wiretapping Law says

MANILA, Philippines — Ombudsman Samuel Martires has accused Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism executive director Malou Mangahas of illegally recording a conversaton that they had earlier this month that was later quoted in a PCIJ report on President Rodrigo Duterte's unreleased Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth for 2018.

In a statement in Filipino on Wednesday, Martires claimed that Mangahas violated the Anti-Wiretapping Law by recording a casual conversation without his consent and without informing him that he was being interviewed. He did not address the claims about the SALN in his statement

But PCIJ said in a statement Wednesday night that Martires and his staff were aware that the conversation, done in a public place on a matter of public interest, was being recorded on Mangahas' mobile phone.

READ: Ombudsman decries 'wiretapping' by PCIJ, mum on Duterte SALN release

What does the law say?

Republic Act No. 4200, or the Anti-Wiretapping Law, was signed into law in June 1965 to safeguard the constitutionally-guaranteed right to privacy of communication.

Philippine jurisprudence outlines the following as conditions for one to violate the law:

- That the person recording is "not being authorized by all the parties"

- That the person records the conversation by tapping any wire or cable, or by using any other device

- That the person commits the aforementioned act to "secretly" overhear, intercept, or record a private communication

- That there must be a third person who will record the communication without the consent of either parties in the conversation

The law states that anyone who knowingly possesses, replays, or communicates recordings of wiretapped communications along with anyone who knowingly aids or permits wiretapping, is likewise held liable.

Jurisprudence also holds that whether one was part of a private communication or not, it does not matter who made the unconsented recording in question. Additionally, the law makes no distinction on where the recording was done.

In 2018, the law was expanded to cover public telecommunication entities retaining data and recordings by means of voice and data transmission.

Under the law, authorities are only allowed to wiretap in the event of cases involving treason, espionage, sedition, rebellion, and kidnapping with the condition that they have written court orders.

The case of Salcedo-Ortanez vs.Court of Appeals also holds that if there is evidence of a clear showing that both parties to the conversation allowed its recording, then a recording is not illegal. The case also provides that the best evidence for this is usually in the recording itself.

'Wiretapping' in a wireless world

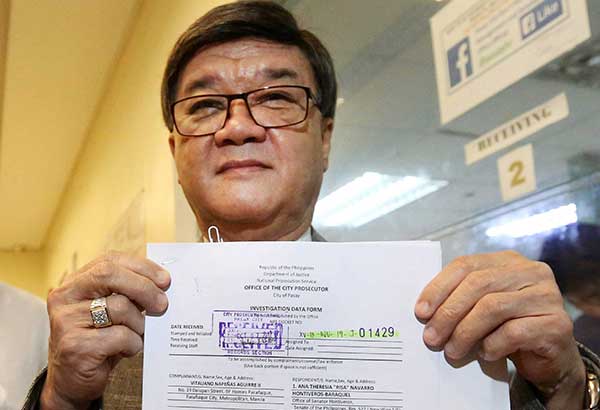

In October 2017, then-Justice Secretary Vitaliano Aguirre II filed a complaint accusing Sen. Risa Hontiveros of violating the Anti-Wiretapping Law after the senator, in a privilege speech, showed a photo of a text message exchange between Aguirre and a certain “Cong. Jing”, presumably lawyer and former lawmaker Jing Paras.

Hontiveros said the photo, taken at a Senate hearing "inadvertently captured a text message exchange on the screen of the phone of Aguirre."

She noted that when zoomed in, the photo shows Aguirre exchanging texts with a certain "Cong. Jing" where the justice chief is said to be ordering the latter to hasten the case build-up against Hontiveros.

RELATED: Aguirre and Hontiveros come to court

Paras, in September, filed a complaint at the Office of the Ombudsman accusing Hontiveros of violating the Anti-Wiretapping Law "by using a device (camera) to secretly record a private communication between a certain Cong. Jing and Secretary Vitaliano Aguirre consisting of the exchange of text message between the two ...without being authorized by both parties who were in communication with each other."

One case involving a journalist was that of broadcast journalist Cecilia “Che-che” Lazaro, who was charged in 2010 with supposedly wiretapping her private conversation with an official of the Government Service Insurance System (GSIS).

A journalist, Lazaro allegedly recorded part of her conversation with private complainant Ella Valencerina of the GSIS without her consent and later aired them over a segment entitled “Perwisyong Benepisyo.”

Lazaro was eventually acquitted of the charges with the court citing lack of evidence. The 28-page decision reads: "The prosecution failed to discharge its burden in proving the guilt of the said accused beyond reasonable doubt because all the foregoing elements of the offense were not established."

Valencerina’s own court testimony admitted she had been informed and was aware that Lazaro was recording their conversation. The latter in her testimony was quoted as saying, "she already told me that she was recording it."

In the case against Lazaro, the court held that "when the accused recorded the phone conversation she had with private complainant Ella Valencerina who has knowledge of this recording, this act was not meant to tap. It was a simple recording by a reporter of a conversation which is not punishable by law."

- Latest

- Trending