The fault in our system: How to fix elections in the Philippines

MANILA, Philippines — Among Southeast Asian countries, the Philippines has had the longest history of democratic elections but the country still has a long way to go in terms of protecting the integrity of one of the exercises of democracy — the right to vote.

Human rights advocacy group Freedom House labeled the Philippines as “partly free” in the 2019 world freedom index with a score of 61 out of 100. Aside from the Philippines, other Southeast Asian countries deemed partly free were Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar and Singapore.

Freedom House defined “partly free” countries as those with “limited respect for political rights, and civil liberties and often a high rate of corruption, weak rule of law, ethnic-religious strife and a dominant political party despite the façade of pluralism.”

The current electoral system in the Philippines faced several changes over the years as attempts to stem persistent issues such as campaign violence and massive fraud.

What went wrong

The 1949 elections, for example, was labelled as the worst elections held in the Philippines due to mass electoral fraud, which mostly occurred in Lanao and Negros provinces. Most of the votes turned out in favor of candidates of the then ruling Liberal Party.

In a journal article published March 1954, Ohio University professor emeritus Willard Elsbree recalled how a Commission on Elections (Comelec) official declared that “there is no more democracy in the Philippines” during the 1949 election season.

“Fraud and violence were rife. On election day, members of the constabulary and ‘good squads’ roamed the streets to intimidate supporters of the opposition party. Registration lists were padded to almost comic proportions. It was said that ‘the birds, the bees and the flowers’ voted in some districts where the number of votes nearly equaled the total population,” Elsbree wrote.

An amendment on Section 76, Republic Act 180 or the Revised Election Code, passed on June 1947, gave way to this massive electoral fraud as it denied the Comelec authority in the appointment of the board of election inspectors (BOI).

Following pressure from poll watchdog National Citizens’ Movement for Free Elections (Namfrel) prior to the 1951 elections, the Comelec initiated reforms to address concerns on electoral fraud. Namfrel was founded that year to stand as a non-partisan election monitoring group to prevent election fraud and has since done this task until the 2016 elections.

One of the revisions that the Comelec made was to require that the BOI be composed of one representative each from the majority and minority parties and an independent appointee. Note that in the 1949 polls, the election inspectors were dominated by the majority party.

De La Salle University professor Cleo Calimbahin, an expert on electoral reform, wrote in an article titled “Capacity and compromise: COMELEC, NAMFREL and election fraud” that the poll body made changes in the system such as giving itself the authority to assign polling precincts, prepare voters’ list and handle ballot management.

In an attempt to prevent so-called flying voters, the Comelec also imposed a residency requirement for voters.

By 1986, the Comelec would be known as “highly partisan” and “biased” under the Marcos dictatorship. Namfrel played a key role in the elections that year by providing an alternative quick count.

“Consistently used as an instrument for vote manipulation during the pre-martial law period, the Comelec did not initiate reforms after 1969 as Marcos had the commission a part of his machinery and extended patronage both to the commissioners and the larger Comelec bureaucracy,” Calimbahin wrote.

Until 2007, the Philippines used the manual election system, which was noticeably vulnerable as it was hard to pinpoint whether there was human error or a deliberate attempt to manipulate results.

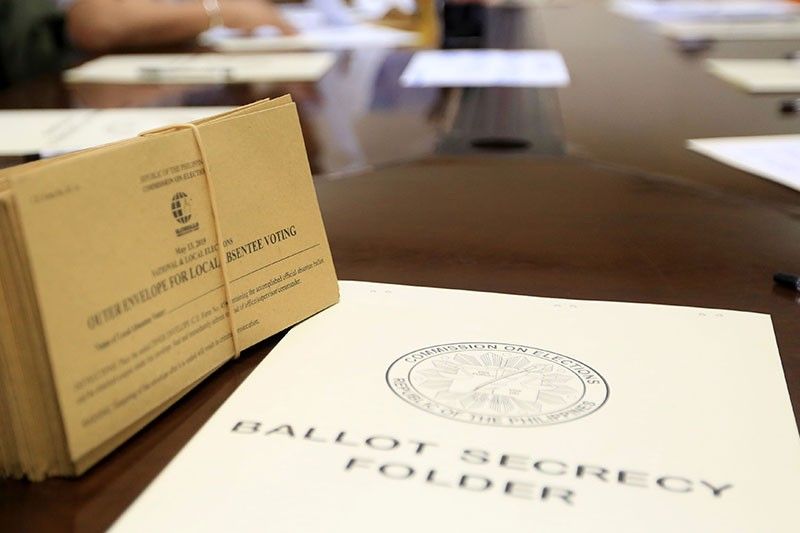

Shift to automated elections

Louisiana State University professor Abigail Peralta, in a study titled “The impact of election fraud on government performance,” noted that some types of electoral fraud that occurred during or after election day were ballot box stuffing, vote padding or “dagdag-bawas” and outright fabrication of election returns.

The Philippines shifted to automated elections in 2010 in a bid to counter election fraud as the transmission of results were faster.

While the security and transparency features that came along with the shift to automation ensured that the results did not get tampered with, transmission problems hounded the precinct count optical scan or PCOS machines.

The PCOS machines, which were first used in the 2010 polls, were found to have problems when they were reused in the 2013 elections, as reported by the Comelec Advisory Council. The same problems seen in the 2010 elections were also encountered in 2013.

“There were at least five types of machine malfunction, classified as follows: a. The machines failed to initialize; b. Some machines started well but stopped functioning after a few ballots were fed into it; c. Paper jamming; d. The back-up memory cards simply did not work; e. The machines rejected the ballots fed,” the Comelec council said in its 2013 post-election report.

In 2015, the Comelec renamed the PCOS and Optical Mark Reader machines to "vote counting machines" or VCMs, as the previous names earned the nicknames “Hocus-PCOS” and “O-MaR,” alluding to former Interior Secretary Mar Roxas.

The STAR columnist Jarius Bondoc noted that re-baptizing the machines prior to the 2016 elections “does not conceal the crimes via the PCOS.”

Fixing the system

As of September 2018, the Comelec has made 82 enhancements to ensure the integrity and accuracy of the 2019 midterm elections. These improvements were based on independent and internal audits, as well as reviews of IT experts, following allegations of fraud in the 2016 elections.

According to the Comelec, some of the enhancements for the 2019 polls are making the ballot ovals thicker, generating raw data from precinct results, automatically printing statistics reports of VCMs after the end of voting hours.

Despite all these efforts to protect the integrity of the automated polls, attaining a credible election system goes beyond the election process itself.

Australian National University Paul Hutchcroft, in a television interview April 29, noted that strong patronage systems and weak political parties have brought down the quality of democracy in the Philippines.

Hutchcroft is the editor of a book titled “Strong Patronage, Weak Parties: The Case for Electoral System Redesign in the Philippines,” which looked into the “territorial politics that run Philippine government.”

“If there were a goal of addressing those two issues — strength of patronage structures and the weakness of political parties — one of the best ways to do that would be through electoral system redesign,” Hutchcroft told ANC’s Early Edition.

The book referred to the electoral system as the formulas used to “convert votes to seats,” arrangements to elect national and local executives, district magnitude and ballot structure.

Personalities and political parties

Hutchcroft described the Philippine electoral system as “quite unusual” as 80% of elected officials are elected through a multimember plurality system.

The Philippines uses a mixed-member majoritarian system, where part of the legislature is elected by proportional representation and the rest from local districts, according to a Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung paper published September 2007. In the Philippines' case, the senators are elected at the national level through plurality votes while members of the House of Representatives are voted through local districts.

Hutchcroft said that the current system guarantees a high level of intraparty competition” that “weakens the cohesiveness” of political parties in the country. Senatorial candidates, for example, compete with each other, regardless of political party, to take one of 12 slots. This makes the competition personality-based rather than party-centric.

This explains the presence of so-called political butterflies or politicians who easily transfer political affiliations. Note that in 2016, several Liberal Party congressmen moved to President Rodrigo Duterte’s Partido Demokratiko Pilipino-Lakas ng Bayan, giving birth to the so-called supermajority at the House of Representatives.

Having genuine political parties in the Philippines would probably make the elections more credible but pending House Bill 7088 or an act strengthening the political system only seeks to introduce reforms in campaign financing, promote party loyalty and encourage voters' education.

Senate Bill 226 or the Political Party System Act also seeks to strengthen political parties by making changes in campaign finances but also suggests promoting party loyalty and instituting measures to “professionalize political parties and make them viable instruments of development and good governance.”

Party-lists and other oddities

In the same book, DLSU professor Julio Teehankee also mentioned the country’s party-list system as odd as it is not found anywhere else in the world. Under the Constitution, 20% of the total number of seats in the House of Representatives should be allotted for party lists.

“Its three-seat ceiling not only violates the principle of proportionality but also leads to the proliferation of small and ineffectual parties,” Teehankee wrote.

Voters can only choose one party lists out of hundreds that apply for accreditation with the Comelec. The party list system, however, had given way for politicians who do not come from the marginalized sector but become nominees anyway.

Despite concerns raised on the qualification of several nominees, the Comelec said it would not change the guidelines of the party-list elections. Rather than abolishing the party list system, the poll body can implement changes that would prevent personalities would not dominate it and ensure that the country’s marginalized sectors have representation in the lower chamber.

Hutchcroft, in “Strong Patronage, Weak Parties,” also listed the separation of the election of the president and vice president; governors and vice governors; and mayors and vice mayors as challenges to the Philippine election system.

“This separation is very rare internationally, as it opens up the possibility (frequently realized) that the two top officials of the land (as well as the province, city and municipality) will come from different political parties,” Hutchcroft said.

--

Perhaps the Philippines, particularly the Comelec, could look at other countries’ election management bodies that have evolved to strengthen the people’s participation in a democracy. The Philippines may have been one of the oldest countries in Southeast Asia to hold democratic elections but it needs to keep up with the rest of the world that have evolved their electoral systems.

Since the 1949 elections, dubbed as the first systematic, successful electoral fraud in the country, the Comelec had struggled to maintain its integrity. As the Philippines undertakes another election, the poll body was given another opportunity to carry out its mandate and be independent and impartial in leading the electoral process.

Several tweaks in election rules have been implemented in the past decades but the Comelec should also consider other election-related rules, systems and design that would serve as game changers in Philippine democracy.

- Latest

- Trending