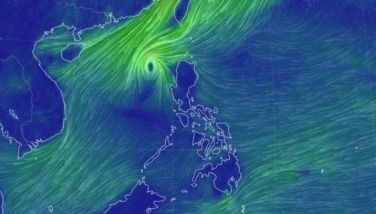

Farmers risk death to save crops from killer 'Ompong'

BAGGAO, Philippines — As Typhoon Ompong (international name: Mangkhut) hurtled toward the Philippines, those in its firing line had a stark choice: stay or flee. Many chose to remain in order to protect their most precious possessions—their food and livestock.

Residents of the storm's ground zero, in Baggao on the eastern flank of Luzon island, knew they would be hit full-force, but losing their livelihoods was a disaster they were willing to risk everything to prevent.

"Our house was blown away. We were flooded," Diday Llorente, 55, told AFP. "But we did not evacuate because we didn't want to leave our carabao (water buffalo) and livestock."

Llorente lives in the coastal farming area of Baggao that is home to some 80,000 people, and which took a direct hit from "Ompong" when it made landfall there in the pre-dawn darkness on Saturday.

In this key farming region of northern Luzon island, a quarter of the people live in poverty— getting by on less than US$2 per day.

Like many in the region Llorente is a small-scale farmer, eking out a fragile existence from the land. The two hectares (five acres) of corn she farms with her husband were drowned in flood waters.

For farmers like her, there is no insurance to compensate for a destroyed crop or dead cow, and no rainy-day savings to bridge the gap.

"If we think from their perspective, these are really their greatest assets... whatever little they have is all they have," Lot Felizco, country director for Oxfam Philippines charity, told AFP.

"It's really heartbreaking... for people who already live in a very difficult and dangerous situation. What choices do they have?" she asked.

'No means to live'

The decision not to evacuate can have horrendous consequences. Many of the 7,350 people killed or missing in the nation's deadliest storm, Super Typhoon Haiyan of 2013, did not heed warnings of a heavy storm surge.

Yet, for those in Baggao the threat of losing their produce, to the violent weather or to thieves, has a powerful influence.

Aida Acopan, 59, evacuated from her home during the last massive storm that struck the area, 2016's deadly Typhoon Haima. She survived, but at a cost.

"Someone broke into my house and stole half a cavan of rice... so I didn't want to take any chances this time," she said.

The loss was roughly 25 kilos (55 pounds) of the staple that is consumed at every meal in the Philippines. Having sufficient supplies of it is a primary concern in rich and poor households alike.

With that roughly $10 loss in mind—worth more than a week’s income for the Philippines’ poorest people—and after days of increasingly urgent warnings from authorities last week, she came to a decision about what to do this time.

"We decided not to evacuate," she said, standing outside her battered, but still standing home of concrete blocks and wood.

The other problem with evacuating is that it does not come with any guarantees. Shelters in the Philippines are basic affairs, usually just some floor space in a school or gymnasium.

"They (evacuees) lose whatever little control they have over the situation," said Felizco.

But there are no guarantees either that staying with one's crops or animals will mean that they survive.

In the case of "Ompong," gusting winds topped 255 kilometers (160 miles) per hour and some areas got a month's worth of rainfall in a matter of hours.

Mary Anne Baril stayed in her home as the typhoon uprooted trees, snapped power poles in half and flooded farm fields, including hers.

"We're already poor, then this storm happened to us," she told AFP as she brushed away tears. "We have no other means to live."

- Latest

- Trending