Resist, adapt, submit: Barangay officials make tough choices in the drug war

PCIJ Story Project — January 21, 2018. It’s fiesta time in Tondo, Manila. High-spirited marching bands compete with the trill of videoke machines on nearly every corner. It is almost impossible to navigate the winding alleys without tripping on a child.

Entire families and gangs of children are out on the streets, wearing the orange, blue or red of their respective neighborhoods, each shade representing one of Tondo’s 300 barangays. Over 600,000 people live in Tondo, crammed in an area less than nine square kilometers.

When Oplan Double Barrel, the government’s anti-drug campaign, was launched nearly two years ago, Tondo’s barangay captains faced tough choices. Throughout the country, local leaders were told to submit a watchlist of suspected drug users and dealers in their communities. They were supposed to share those lists with the police, who then conducted operations that resulted in drug suspects being killed.

It is hard to know the precise number of drug-related killings. Based on data we collected from news reports, there were at least 380 drug casualties in the city of Manila from July 2016 to December 2017. Tondo has one of the highest casualty rates: 117 of those killings, 30 percent of the total, took place in Tondo.

Data from the Manila Police Department show that between July 2016 and February 2017, Police Stations 1 and 2 in Tondo conducted 77 operations that resulted in 88 casualties. These figures, however, include only those killed during uniformed police operations, not vigilante and other type of killings.

This is the story of three barangay officials in Tondo who responded to Oplan Double Barrel in different ways.

Barangay officials have the power to decide the shape of the war on drugs—they have the choice to go along with death, to submit to authority, or to adapt and resist.

But such power is constrained. Village officials have to comply with the directives of the national government. Refusal to do so may be seen as complicity with the drug trade. Authorities have said they have a list of over 200 barangay officials involved in illegal drugs. The president himself has that “if those backed up by drug money will win as barangay captains, it will be another war. It will be another killing.”

The barangay is the linchpin of the administration’s anti-drug operations. Faced with national government directives on an all-out war on drugs, what should barangay officials do?

The bureaucracy of the drug war

The barangay, the basic unit of Philippine governance, is the smallest cog in the drug war’s machinery. But it is an important one. There are over 42,000 barangays throughout the country. The barangay chairperson (or punong barangay) and members of the Sangguniang Barangay (council members, popularly called kagawad) are the elected officials with the closest claim to direct community representation.

As the primary planning, implementing and dispute-resolution unit under the 1991 Local Government Code, any major government directive—whether it concerns vaccination, nutrition or peace and order—needs the cooperation of the barangay if it is to be implemented.

While the police are the most visible instruments of the drug war, they are only one of the many agents and institutions that have been mobilized for the Duterte administration’s anti-drug campaign. There is an entire bureaucracy behind the war on drugs. The barangays, like the police, are at the frontlines.

President Rodrigo Duterte promised to eradicate illegal drugs within three to six months.

The Philippine bureaucracy quickly took on this directive from top to bottom. The “10 Point Socio-Economic Agenda,” prepared by the government’s economic planning agency, became the “0 + 10 Point Socio-Economic Agenda,” with zero as the fight against criminality and drugs. This fight, said Economic Minister Ernesto Pernia, is a prerequisite “for the economy to thrive and flourish and for the country to prosper.”

An Interagency Committee on Anti-Illegal Drugs also brought together 20 national government agencies to “suppress the drug war in the country” by arresting both big-time drug dealers as well as street-level peddlers and users.

The committee implements various instruments such as the National Anti-Drug Plan of Action (2015-2020), which focuses on law enforcement, and the Barangay Drug-Clearing Program, which mobilizes barangay officials to list, monitor and conduct surveillance of drug users and dealers in their communities.

Nominally headed by the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency and the Dangerous Drugs Board, much of the committee’s work is carried out by the Department of the Interior and Local Government. The DILG has oversight over the Philippine National Police. It also oversees all local government units.

In September 2016, the DILG issued a memorandum circular that launched a national grassroots surveillance program aimed at using citizens to monitor and report drug, crime- and terrorism- related activities. This program is called MASA-MASID or Mamamayang Ayaw sa Anomalya, Mamamayang Ayaw sa Iligal na Droga (Citizens Against Anomalies/Corruption, Citizens Against Illegal Drugs).

MASA-MASID overlaps with the Barangay Anti-Drug Abuse Council (BADAC). These councils have existed for some time, but they were largely moribund. Composed of barangay officials and representatives from the church and local organizations, BADACs are supposed to coordinate on implementing drug monitoring and rehabilitation programs.

The DILG said that only half of all barangays in the country had a BADAC as of December 2016; today, 70 percent of them do. Officials in the remaining 30 percent have been threatened with administrative charges if they do not activate anti-drug councils.

The DILG’s directive instructs city or municipal governments to consolidate anti-drug operations efforts. For example, they put together the lists of names of suspected “drug personalities” collected by the barangay. The City Anti-Drug Abuse Council (CADAC) also supports the BADAC and helps organize activities for drug addicts and other community members. This can include counseling, sports fests, Zumba dancing, tree planting, and if resources are available, livelihood activities.

Government funds are made available for these efforts.For 2018, the DILG proposed a P500-million budget for MASA-MASID alone, while the PNP proposed P900 million for Oplan Double Barrel.

At the local level, the drug war has changed the way barangays spend their funds, which come from a 25-percent share in real-estate taxes collected from their communities. Traditional social services such as medical clinics or feeding programs for malnourished children are no longer budget priorities. Through a number of policy incentives as well as strict supervision by the DILG, the priority at the barangay level has now become the monitoring and surveillance of drug suspects and the rehabilitation of drug users who have surrendered.

In a span of almost two years, the anti-drug campaign has become so deeply embedded at the grassroots level. In some cases, it has turned neighbor against neighbor, family against family. In all of these, the barangay, the smallest, often neglected unit of governance holds the key. Barangay officials exercise discretion in how they implement the drug war in their communities. They play a critical role in determining who lives, who dies and who gets rehabilitated in the war on drugs.

Barangays’ roles in the drug warIn 2017, the DILG issued a circular that instructs barangay officials to do the following to support the drug war:

|

Chairman David: The path of resistance

In one of Tondo’s densest neighborhoods, the barangay chairman takes his daily afternoon patrol. The children reach for his hand, all of them screeching, “Mano po, Che!” Che is short for chairman.

In one of Tondo’s densest neighborhoods, the barangay chairman takes his daily afternoon patrol. The children reach for his hand, all of them screeching, “Mano po, Che!” Che is short for chairman.

The chairman is a former engineer; he asked to be identified by the name David so he could talk freely. David thinks of himself as the father of the barangay; the constituents are his children.

David was adamant that he would not let his constituents die. He was also clear that no police operation would be carried out in his area without his knowledge. The last thing he wanted were neighborhood kids becoming collateral damage in the drug war.

David chose the path of resistance. He tries to pre-empt the police. “I use my network across different levels of the bureaucracy,” he said. “I get advanced information so I am a step ahead before the [police] operations are carried out.” Although he still submits a drug watchlist to the authorities, particularly to the DILG, he surreptitiously ensures that all the names on the list are given fair warning they will be on the list and they should, therefore, be careful.

David sees drug use as a health issue and not a criminal one. He uses the BADAC not to target drug users but to save them. He puts drug suspects in the barangay jail if he fears for their safety or sends them back to their home provinces so they will not be targeted.

David said the local police are his friends and they leave him alone as long as they are not compromised by his behavior and seen as being soft on drugs.

Through the BADAC, which is tasked with conducting drug-education programs, David and his kagawad were able to convince suspected drug users to surrender and undergo community-based drug rehabilitation. David assured the drug users and dealers who surrendered that he will monitor their progress and make sure they finish the program so that they can be stricken off the watchlist.

Since the last quarter of 2016, David’s barangay has jailed three people and the BADAC there is actively monitoring 32 others for eventual removal from the barangay drug watchlist. Many were made to go to regular counseling sessions, while some have been sent to the Magsaysay Health Center in Fugoso, Manila for additional treatment.

These activities, however, are costly. There are increasing numbers of drug “surrenderees.” David’s barangay has some 1,000 residents and its annual budget is a little over P900,000. Of this, some P500,000 is allocated for maintenance and operating costs, including the budget for peace and order and training.

In 2017, the barangay allocated more than P90,000 for drug rehabilitation and P110,000 for training, mostly to build capacity for drug counseling seminars. This is twice the amount they spent on small infrastructure projects like drainage systems and canals. This means that after paying for salaries and utilities, there is little money left over for social services. In many instances, David used his own money to help his constituents.

“In our community, we thank the Lord because no one has died. No one gets killed,” said David. “I had a few that I sent to jail, and a few that I sent back to the provinces. But no one gets killed.”

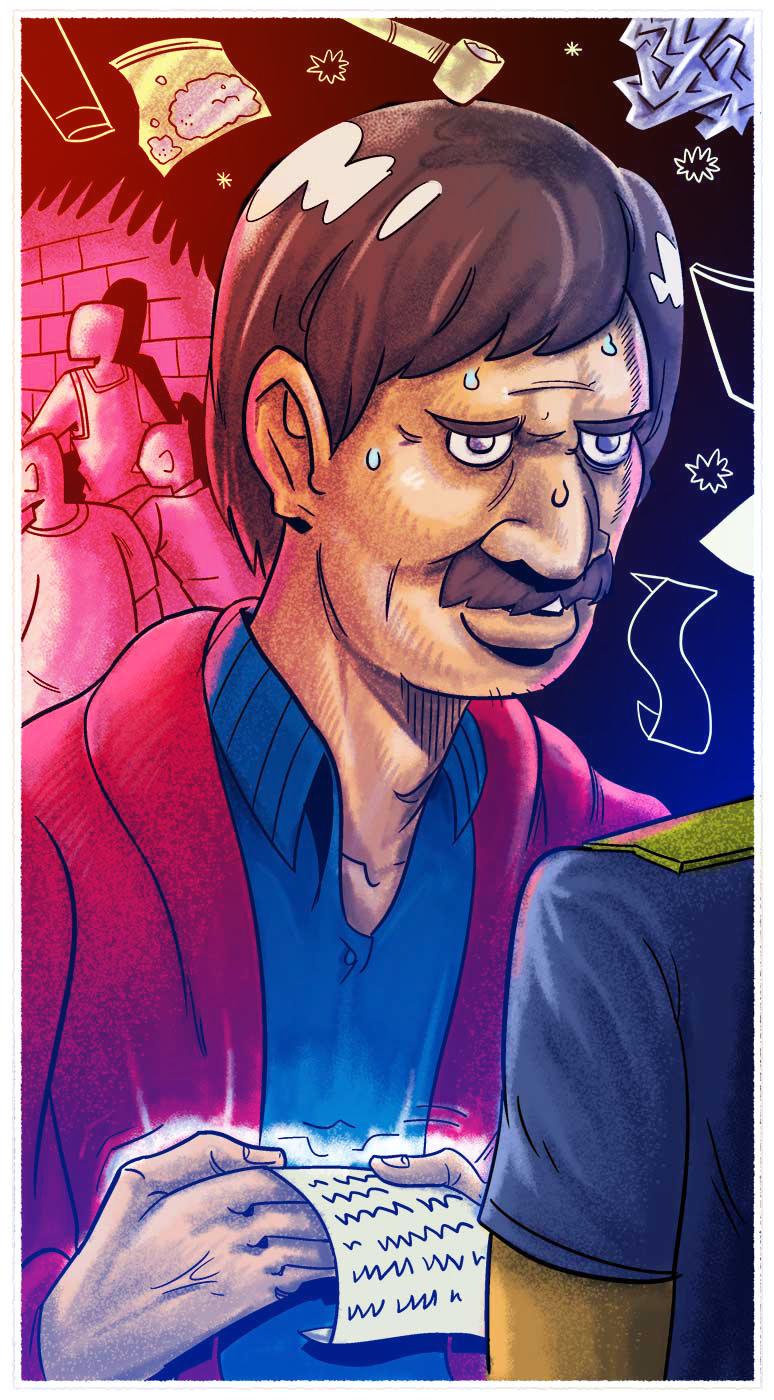

Chairman Roger: Submitting to the drug war

On January 14, the Sunday before the Tondo fiesta, the police raided a suspected drug den in Chairman Roger’s barangay. The operation went smoothly, at least according to the police report that Roger signed. He was not there himself, but Roger trusts the police. The two targeted drug suspects surrendered and no one was killed.

On the days when drug suspects were killed and their corpses were carried off in body bags, Roger signed off on the police reports without question. “Whatever evidence [the police] say they found, I’ll sign it. They know what they are doing.”

Chairman Roger, who asked to be identified only by a pseudonym, has always been staunchly against drugs. For many years, he worked as a seaman, spending many lonely months at sea. He was on a ship when he got word that his two brothers were jailed for using and selling drugs. This prompted him to return to the Philippines and later, to run for barangay kagawad, a post he held for ten years before running for barangay chair.

The Philippines “has always had a drug problem,” Chairman Roger said. “I’m glad something is being done about it.”

Roger has conceded nearly absolute authority over his barangay to the police when it comes to the drug war and peace-and-order programs.

Before the Duterte presidency, Roger’s barangay had a help desk manned by a kagawad who coordinated with the police. Now, the help desk is gone and police freely come and go without any interference from barangay officials. In the past, the police informed the barangay chair in advance of any police operations in the community. These days, Chairman Roger just waits for the police reports to arrive.

Roger said that his barangay regularly provides the police and the DILG information about drug suspects and also a watchlist made up of suspected drug users and dealers in the community. When we spoke to him, he said he had 13 on his watchlist. Two of them had already been killed.

He attested to the improvements in his barangay since the drug war. The place isn’t as chaotic as it used to be, he said, and teenagers rarely loiter in the streets at night.

“People are finally afraid of the police,” he added. When asked about the victims killed by vigilantes and police operations, Roger gave pause. “[The victims] are bad people anyway,” he said.

“I too dream of a drug-free Philippines,” Roger said. “But why does it have to be so bloody?” When asked if he has raised his doubts with the police, he shook his head. “I don’t argue with the police. They have guns. We don’t.”

Kagawad Angela: Bending with the wind

In the afternoon of the Tondo fiesta, Kagawad Angela is not in the barangay hall. She is at home, cooking her family’s feast day meal. The menudo is still on the stove and she is behind schedule.

Angela’s home is a five-minute walk from the barangay hall. This is convenient for a solo parent like her because she can leave her office for a few minutes during the day to check on her children.

Angela is a reluctant leader. Prior to being a kagawad, she was a housewife. It was her husband who was in public service for 27 years as a barangay kagawad and chairman until he was gunned down last October, one of the thousands killed in the war on drugs.

“He was shot by unknown killers. It’s still under investigation. I would rather not [talk] about it,” Angela says.

As kagawad, Angela is aware of the drug problem. She believes this is symptomatic of larger problems rooted within families, including financial difficulties. Her barangay is one of the biggest and poorest areas in Tondo.

“We have a population of 22,000 people. Most are poor,” she said. “They live by the day, as pedicab drivers, vendors in Divisoria, or porters in MICT (Manila International Container Terminal). Because this is the environment, sometimes the children want to try sniffing solvent, which can become a habit until they grow up.”

Since her husband the barangay chairman was murdered, her barangay has yet to comply with certain requirements set by the national government—including the submission of an anti-drug plan.

Angela is evasive when asked about the barangay drug watchlist. She says the list is assigned to another kagawad, and she does not know where it is. She is sure, however, that the drug war has claimed more people in her area besides her husband. “There isn’t much we can do,” Angela admits.

In lieu of the anti-drug plan, Angela works instead on her own barangay Kumustahan Program which targets the teenagers of the community. At the heart of her efforts is prevention—both of drug use and death because of the drug war. While she may be powerless to help the adults on the drug watchlist who may already be targeted by masked killers, Angela engages teenagers and children in counseling sessions.

“We have to go to the root of the problem. With drugs or petty crime, find out why people do it. That’s the only way we will know how to help them,” she said. “We have to fix the family first. Then the barangay, then the community. That’s the only way we can fight drugs.”

But Angela takes punitive measures as well. “If I catch [a teenager] stealing, I lock them up in our jail for three hours, so they know what kind of life they will have if they continue [to commit crimes].” She pointed to a small makeshift jail cell underneath the stairs of the barangay hall. “If I catch kids high on solvent, I make them squat 100 times so they will sweat the high out.”

After the interview, Kagawad Angela walked back to her house so she can finish her cooking and celebrate Tondo’s feast day with her children. On the way home, she pointed to the exact spot where her husband was shot just three months before.

— Illustration by AJ Bernardo, Miguel Punzalan and Josel Nicolas

- Latest

- Trending